Definition 1

The Heian period is a period in Japanese history that began in 794 and lasted until 1185. The word "Heian" means peace and tranquility.

The Heian era in Japan lasted 4 centuries. The period begins with the fact that the imperial capital of Nara was, by order of the emperor, moved to another city - Heian-kyo (today the metropolis of Kyoto), and ends with the naval battle of Dannoura, in which the Minamoto clan defeated the Taira clan. Although this period is called “peaceful”, it is difficult to call it peaceful and calm

Heian era in Japanese history

This period is characterized by the penetration of Chinese civilization into Japan, with the arrival of which not only Buddhism, but also Chinese literature and architecture came to Japan. Even the forms of government, along with laws, were also borrowed from the Chinese rulers. If earlier the power of the emperor was limited by the influence of Buddhist monks, then after the transfer of the capital, the Japanese emperor began to implement the knowledge received from China, but not all borrowed forms of government were suitable for Japan, much was adjusted and modified in accordance with the needs of the state.

Are you an expert in this subject area? We invite you to become the author of the Directory Working Conditions

Many orientalists characterize the new capital of Heian as a great and beautiful city. The board during this period was organized quite complexly, all levels of officials were intertwined with each other in close ties.

Despite its rapid development, Japan remained alienated from the other world, as evidenced by literary sources and architecture of the period. It was during this period that bloody wars engulfed Europe, the first crusades were convened, religious disagreements raged, a civil war broke out in China, and Great Rus' was completely subjected to endless raids by the horde. Against the backdrop of general wars and conflicts, the history of Japan in that period indeed looks relatively peaceful.

It should also be said about the other side of the coin - the luxury of palaces and the splendor of the new capital of the Heian period coexisted with a poor population and crumbling shacks of the poor. So, out of the more than five million population of Japan, only five and a half thousand people who belonged to the imperial court could enjoy the delights of a decent life in the Heian era.

Finished works on a similar topic

Coursework The Heian Period in Ancient Japan and the reign of Fujiwara 420 ₽ Essay The Heian Period in Ancient Japan and the reign of Fujiwara 220 ₽ Test paper The Heian Period in Ancient Japan and the reign of Fujiwara 230 ₽

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

The aristocracy and local nobility were divided into five ranks, which were passed on only by inheritance and had nothing to do with a person’s merits to the state; only the emperor himself had the right to bestow a rank on a person. The height of the rank played an important role; it determined what kind of house a person and his family could live in and what clothes he could wear.

Economy

While on the one hand the Heian period was an unusually long period of peace, it can also be argued that the period weakened Japan economically and led to poverty for all but a tiny number of its inhabitants. Control of rice fields was the main source of income for families like the Fujiwaras and was the fundamental basis of their power.[20] Aristocratic beneficiaries of Heian culture, Ryōmin

(良民 "Good People") numbered about five thousand people in a land with a population of about five million. One of the reasons the samurai were able to seize power was because the ruling nobility proved incompetent in governing Japan and its provinces. By the year 1000, the government no longer knew how to issue currency, and money gradually disappeared. Instead of a fully realized monetary system, rice was the primary unit of exchange.[20] The lack of a lasting means of economic exchange is implicitly illustrated by the novels of the time. For example, envoys were rewarded with useful items such as old silk. kimono, but did not pay a commission.

Fujiwara's rulers failed to maintain a sufficient police force, which gave robbers the opportunity to prey on travelers. This is implicitly illustrated in the novels by the horror of that night's journey inspired by the main characters. In the shōen, the system allowed the aristocratic elite to accumulate wealth; economic surplus can be attributed to the cultural development of the Heian period and the "pursuit of art".[21] Major Buddhist temples in Heian-kyo and Nara also used shōen.[22] The establishment of branches in rural areas and the integration of some Shinto shrines into these temple networks reflects greater "organizational dynamism".[22]

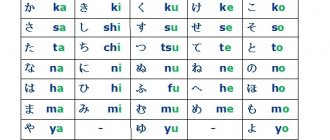

Heian period clothing

The clothing of the court nobility of the Heian period was very similar to Chinese ceremonial costume, the color of the clothing corresponding to the rank. The most valuable colors were red and purple, followed by green. The emperor wore yellow clothes - the color of the sun.

There was also a special code that regulated three clothing options:

- costume for various ceremonies;

- costume for the court nobility;

- suit for officials.

Clothes for holidays and ceremonies were made from especially valuable silk and brocade; clothes for every day were made from hemp fiber or coarser silk and semi-silk.

Often, when sewing clothes, they used multi-colored fabrics with ornaments: flower arrangements, wreaths, family coats of arms, landscapes. It was during the Heian era that the costume for ceremonies that has survived to this day was formed.

Events

- 784: Emperor Kanmu moves the capital to Nagaoka-kyo (Kyoto)

- 794: Emperor Kanmu moves the capital to Heian-kyo (Kyoto)

- 804: Buddhist monk Saicho (Dengyo Daishi) introduces the Tendai school

- 806: Monk Kukai (Kōb-Daishi) represents the Shingon (Tantric) school

- 819: Kukai establishes Mount Kaya Monastery, in the northeastern part of modern Wakayama Prefecture

- 858: Emperor Seiwa begins rule of the Fujiwara Clan[23]

- 895: Sugawara no Michizane stopped the imperial embassies in China

- 990: Sei Shonagon writes Pillow Book

of Essays - 1000–1008: Murasaki Shikibu writes The Tale of Genji novel

- 1050: Military Class Rise (Samurai)[ citation needed

] - 1052: The Byōd-in Temple (near Kyoto) built by Fujiwara no Yorimichi[24]

- 1068: Emperor Go-Sanjo overthrows the Fujiwara Clan

- 1087: Emperor Shirakawa abdicates and becomes a Buddhist monk, the first of the "closed emperors" (insei)

- 1156: Taira no Kiyomori defeats the Minamoto Clan and seizes power, ending the Inshi era[25]

- 1180 (June): Capital moved to Fukuhara-kyo (Kobe)

- 1180 (November): The capital is moved back to Heian-kyo (Kyoto).

- 1185: Taira is defeated (Genpei War) and Minamoto no Yoritomo, with the support (support) of the Hojo clan, seizes power, becoming the first shogun

of Japan, and the emperor (or "mikado") becomes figurehead

Reign of the Fujiwara family

After the capital of the state was moved, the emperor's power strengthened again, the influence of Buddhist monks decreased, but the role of the emperor's advisers increased, whose positions were held by the Fujiwara clan, which managed to remove all other influential clans from state politics, they also supplied the emperor with wives, thereby becoming related to him. The Fujiwara clan took almost all power into their own hands, they ruled as advisers and regents on behalf of the emperor, while the clan owned a large number of estates in Japan.

At the beginning of the 10th century, there was a shortage of state land, and as a result, the implementation of the “Land Grant Law” slowed down. The imperial court changes the tax collection system and transfers tax collection to the provinces, which, having received such a source of enrichment, began to appoint their own governors in the regions. At the same time, wealthy peasants began to abandon state land and raise virgin lands in order to subsequently turn them into private estates. The state took a high tax from such independently developed lands, so the land owners began to donate their property to the aristocracy, and they, in turn, appointed the donors as managers in their new estates, and so a regional layer of nobility began to form, consisting of the peasantry.

In the middle of the 11th century, Emperor Go-Sanjo, who was not a relative of the Fujiwara family, ascended the throne and therefore began to restore the absolute power of one emperor. These reforms were also supported by the next emperor, Shirakawa, who reduced the influence of the regents and transferred the throne to his son and became his main adviser.

ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION OF JAPAN IN THE HEIAN ERA

CAPITAL HEIAN [53]

IMPERIAL PALACE COMPLEX

Ampukuden (Palace of Calm Happiness) is a building near the main internal gate of Semeimon in the western part of the palace complex. The court doctors were stationed here.

Ankimon (Gate of Calm Joy) is the inner gate of the northeastern palace complex.

Butokumon (Gate of Valiant Virtue) is the inner western gate of the palace complex.

Gyokasha (chamber of Frozen Flowers) - located in the northwestern part of the palace complex. Usually the ladies of the court lived there. Red and white plum trees grew at the entrance, so this building was otherwise called Umetsubo - Plum Pavilion.

Giyoden (Palace of the Blessed Light) - located on the eastern side of the Shishinden Palace (the main building of the palace complex). [54]

The heirlooms of the imperial family were kept in Giyoden, and discussions of important state goals took place there. The Giyoden Palace was connected by a gallery to the northern part of the Shunkyoden Palace. The gallery was called Sakon-no-jin (Left Guard), where soldiers from the Imperial Left Personal Guard were stationed.

Genkimon (Gate of Mysterious Splendor) is the northern inner gate of the palace complex.

Joganden (Palace of Contemplation of True Purity) is located in the northern part of the palace complex. It was occupied by officials in charge of the affairs of the women's quarters of the palace. There were also chambers of the Highest Casket (Mikushigedono), where outfits for the imperial family were sewn and stored.

Dzekyoden (Palace Bestowing Fragrances) is a building located in the center of the palace complex, north of Jijuden. Feasts were held here, poetry tournaments and music performances were held.

Zeneiden (Palace of Eternal Peace) is located in the northern part of the palace complex. Empresses and concubines of the highest ranks lived in Zeneiden. As a rule, it was there that the dances of the “five dancers” (“goseti”) were held, so the palace was also called the palace of the five dancers - Gosechiden.

Jijuden (Palace of Virtuous Old Age) is a building in the central part of the palace complex, north of Shishinden. At first, the emperor himself lived in this palace, later, when the Seireden Palace became the permanent residence of the highest person, ceremonial feasts began to be held here, sumo competitions, ball games, etc.

Immaemon (Gate of the Hidden Light) is the inner palace gate. Located on the western side of the complex.

Kayomon (Gate of Joyful Light) is the inner palace gate. They are located on the eastern side of the complex, not far from Shoyosha's chambers.

Kyoseden (Archive Palace) - located on the west side of Shishinden, opposite Giyoden. The Imperial Archives of Kurodokoro were located here. In the southwestern part of the palace there were workshops (tsukumodokoro), where utensils for the highest family were made.

Kianmon (Gate of the Crowned Rest) is the inner northwestern gate of the palace complex.

Kokiden (Palace of Bountiful Awards) - located in the northwestern part of the palace complex, directly behind Jokyoden. As a rule, the most influential concubines lived in Kokiden.

Koryoden (Palace of the Coming Cool) - located west of Seiryoden. Usually high-ranking concubines lived here.

Ryokiden (Palace of Patterned Silks) - located northeast of Shishinden. The Ryokiden housed utensils and robes for Shinto rituals.

Reikeiden (Palace of Scenic Views) is located in the northeastern part of the palace complex. Empresses or concubines of the highest ranks lived here.

Shoyosha (Chambers of Reflected Light) - are located in the eastern part of the palace complex and consist of the Northern and Southern buildings. [55]

The southern one is also called the Pear Pavilion (Nashitsubo) because there is a pear tree growing in front of it. Imperial concubines lived in the chambers of the Reflected Light, and the crown prince often resided here.

Shomeimon (gate that bestows light) is the central gate of the palace.

Shigeisa (Chambers of Bright Landscapes) - located in the northeastern part of the palace complex. The southern building is also called the Paulownia Pavilion (Kiritsubo) because there is paulownia growing in front of the entrance. Less powerful concubines lived here.

Shishinden (Palace of the Purple Chambers) is the main building of the palace complex. It is located in its southern part, therefore it is sometimes also called the Southern Palace (Nadeng). At the entrance on the east side there is a cherry tree and on the west side there is an orange tree.

Xikhosha (Chambers of Sudden Aromas) - located in the northwestern part of the palace complex. The ladies of the court usually lived here, and also housed the head of the Imperial Right Personal Guard (Udaisho) when he stayed overnight in the palace. Not far from the entrance to the chambers of Sudden Aromas there was a tree burned by lightning, so this building was called the Thunderstorm Pavilion (Kannaritsubo).

Seiryoden (Palace of Pure Coolness) - located northwest of Shishinden. The emperor himself usually lived here, and some ceremonies were also held here (Morning greetings on the first day of the year, etc.).

In the eastern garden of the palace there is a stream that forms a small (about 20 cm high) waterfall. One of the courtiers (the so-called guard of the Waterfall) was constantly on duty near this waterfall.

Senyoden (Palace of Revealed Splendor) is located in the northern part of the palace complex. The imperial concubines lived in Senyoden.

Sen'yōmon (Gate of Revealed Light) is the eastern inner palace gate.

Shunkyoden (Palace of Spring Joy) - located southeast of Shishinden. Weapons and ammunition were stored here.

Terakumon (Gate of Long Joy) is the inner palace gate. They are located on the south-eastern side of the complex.

Tokaden (Palace of Ascension to Flowers) - located in the northern part of the palace complex. Empresses and high-ranking concubines lived here.

Ummeiden (Palace of Warm Light) - located on the east side of Shishinden. In the chambers of this palace the regalia of imperial power were kept - a mirror, jasper and a sword.

Higyosha (Flying Fragrance Chamber) is located on the northwest side of Seiryoden. This building is also called the Wisteria Pavilion (Fujitsubo) because there are wisteria trees in front of the entrance. Empresses and imperial concubines lived in Higyosha.

Eyammon (Gate of Eternal Peace) is the inner palace gate (southwest).

Enseimon (Order Establishment Gate) is the inner palace gate (southeast).

Yugimon (Gate of Triumphant Justice) - inner Palace Gate (west). [56]

AN ARISTOCRATIC MANOR IN THE HEIAN ERA

STRUCTURE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN THE HEIAN ERA

State Council (Daijokan) (Table 1)

Highest administrative body. The head of the State Council was the Great Minister (daijōdaijin).

At the beginning of the Heian era, princes of the blood, as a rule, became great ministers, but by the end of the 10th century. this title passed to the regents and chancellors. The position is purely nominal.

Left Minister (sadaijin)

- in fact, the main figure in the State Council, dealing with the affairs of the board.

Minister of the Right (udaijin)

replaced the left minister in his absence. He was in charge of preparing and conducting various court ceremonies.

Minister of the Court (naidaijin)

- a position not provided for by the Taihoryo code. The minister of the court was directly involved in the affairs of the imperial family and replaced the left and right ministers in their absence.

The first minister of the court was Fujiwara Kamatari (614-669) - one of the highest dignitaries at the imperial court. Tenchi (626-671), founder of the Fujiwara clan. After him, ministers of the court were not appointed, and only at the end of the 8th century. this position was restored, although there were periods when only three ministers stood at the head of the State Council - the great, the left and the right.

Senior Advisor to the Minister (Dainagon)

directly subordinate to the great minister.

In charge of all affairs in the absence of ministers. The Taihoryo Code provided for four dainagons, but their number was soon reduced to two. Under Emperor Uda (887-897), the position of deputy senior adviser (gon-dainagon) was established,

resulting in three senior advisers.

Subsequently, the number of deputies increased, and the number of senior advisers correspondingly increased (there were first eight, then six). Gon-dainagon

usually became dainagon over time

.

Second Advisor to the Minister (Tyunagon)

- a position not provided for by the Taihoryo code.

It arose when the number of senior advisers (dainagons)

was reduced to two.

In 756, the position of deputy second adviser (gon-tyunagon) was introduced.

The deputy second councilor usually became the second councilor over time. Performed the same functions as the senior advisor.

Junior adviser to the minister (shonagon).

The main responsibility of the junior councilor was the transmission of imperial decrees.

He kept the imperial seal, the seal of the State Council and the “imperial envoy’s bell” (which was given to every courtier who went somewhere by order of the emperor). By the ringing of this bell, the courtier was supposed to be provided at the stations with everything necessary for further movement. In addition, the junior adviser had to rewrite the main Decrees and resolutions. [58]

State Council (Daijokan) (Table 1)

[59]

After the Imperial Archives

(Kurododokoro) was established in 810,

many of the functions of the junior advisors were transferred to the archivists

(Kurodo),

and only the bell and seals remained in their charge.

Left and Right Audit Offices (Sabenkan, Ubenkan) -

reported directly to the State Council. The auditors supervised eight departments. Each office supervised the activities of four departments (Table 2), having at its disposal all their documentation. Auditors, as a rule, were appointed from among scientists.

State Councilors (sangi, saisho)

- a position not provided for by the Taihoryo code. Advisors were part of the State Council and were involved in the discussion of the most important state affairs on an equal basis with ministers and their advisors (dainagons). Typically, people known for their learning were appointed to this position. Advisors, as a rule, simultaneously occupied leading positions in other departments.

Vice advisors (hisangs)

- persons of the Fourth rank (and not the Third, necessary to become an adviser), for a number of reasons allowed to participate in the discussion of state affairs on an equal basis with advisers.

Eight departments (Table 2)

1. Department of Palace Services (Nakatsukasasho)

- was in charge of the internal affairs of the imperial palace.

The head of the department (Nakatsukasakyo) became a person of the Fourth rank, usually a prince of the blood. One of the most significant positions in the Department of Palace Services was the position of a close servant (jiju).

Young men from the most noble families of the capital, with the Fifth Rank and who had recently begun serving in the palace, were usually appointed to this position.

Jiju

had to constantly be with the emperor, take care of him, monitor the fulfillment of his wishes, and observe the strict adherence to etiquette.

Often a jiju

also had a position in the State Council, being an adviser to the minister

(dainagon

or

chunagon)

or a state adviser

(sangi).

The Department of Palace Services had six departments under its subordination (ryo

or

tsukasa)

and the Service of the Middle Chambers

(Tyugusiki).

Heads of departments (then)

Fifth rank officials were appointed.

The head of the Middle Quarters Service (daibu)

was an official of the Fourth Rank.

2. Ceremonial Department (Shikibusho, Nori no Tsukasa)

- was in charge of all palace ceremonies and their preparation, dealt with educational issues and supervised the activities of civil officials.

The head of the department could only be a blood prince of at least Fourth Rank. Head of department (shikibukyo)

had at his disposal two assistants appointed from among the officials of the Fifth Rank.

The senior assistant was usually the emperor's mentor. [60]

Eight departments (Table 2)

[62] The Chamber of Science and Education (Daigakuryo) was subordinate to the ceremonial department.

directly involved in the preparation and training of government officials.

The head of the Chamber of Sciences (go)

usually determined the order of major holidays and supervised their preparation.

3. Department of Order and Establishment (Jibusho, Osamuru-tsukasa)

- dealt with various litigations, was in charge of pedigree issues, in families above the Fifth Rank resolved disputes about inheritance, marriages, establishing seniority among family members, supervised funerals, preparations for state days of mourning, was in charge of monasteries and the reception of foreign ambassadors.

Head of the department (jibukyo)

there could be a person no lower than Rank Four.

The department was subordinate to three departments, the heads of which were

Fifth rank officials were appointed.

Music Chamber (Gagakuryo)

— trained dancers and musicians for palace festivities, and trained young men from aristocratic families in dancing, singing and music.

Chamber of Embassies and Monasteries (Gembaryo)

- was involved in sending ambassadors to other countries and receiving foreign embassies, and was in charge of the affairs of monasteries.

Imperial Tombs Department (Söröryo)

- was in charge of organizing funerals for members of the imperial family, and exercised control over the condition of the tombs.

4. Tax Department (Mimbusho)

- was in charge of registering the population, collecting taxes and assigning labor duties.

Head of the department (mimbukyo)

there could be a person no lower than Rank Four.

The department was subordinate to two departments: the Department of Finance (Kazue no Tsukasa),

which was in charge of population accounting and controlled the financial condition of the country, and the Tax Administration

(Chikara no Tsukasa),

which was in charge of the direct collection of taxes and the assignment of labor duties.

Heads of departments

Fifth rank officials were appointed.

5. War Department (Hyobusho, Tsuwamono no Tsukasa)

- was engaged in the training of soldiers, the preparation and formation of military detachments, was in charge of military ammunition, stables, etc.

Head of the department (hyobukyo)

a prince of the blood of no lower than the Fourth rank was appointed.

The military department was initially subordinate to five departments: cavalry, construction, military music, navy, and hunting. Later, the departments were partially merged, partially liquidated, and only one Palace Gate Security Supervision Department (Hayato no Tsukasa) remained directly subordinate to the Military Department.

which controlled the activities of the palace guard.

Head of the Supervision Department (kami)

was a Sixth Rank official.

6. Judicial department (Gyobusho)

— dealt with the consideration of petitions and the imposition of punishments for offenses.

Head of the department (gyobukyo)

there could be a person no lower than Rank Four.

[63]

The Department of Prisons (Hitoya no Tsukasa) was subordinate to the department.

in charge of the maintenance of prisoners.

Head of the Branch (Komi)

appointed from among the officials of the Sixth Rank.

7. Department of Treasury Affairs (Ookurasho)

- took into account and distributed income coming from the province, set prices, and was in charge of storing gold, silver, and precious stones.

Head of the department (okurakyo)

a person of no lower than Fourth Rank was appointed.

At first, the department had at its disposal five departments: metal utensils, lacquerware, sewing, weaving, and palace decoration. Then the departments merged or were liquidated, and there remained one Department of Weaving (Oribe no Tsukasa),

the head of which

(Komi)

had, as a rule, the Sixth rank.

8. Department of Internal Palace Affairs (Kunaisho)

- was in charge of all services related to the internal life of the palace.

Head of department (kunaikyo)

usually had the Fourth rank.

Subordinate to the department: Service of Imperial Meals (Daizen-shiki)

led by

Daibu,

who was appointed from the Fifth Class officials;

five departments (ryo

or

tsukasa)

headed by

go,

appointed from officials of the Fifth rank, and five departments

(tsukasa)

headed by

sho,

who, as a rule, had the Sixth rank.

Six guard services (Table 3)

1. Left and Right personal imperial guards (Sakonoefu, Ukonoefu)

- guarded the imperial palace, accompanied the emperor on trips.

At the head of the guard was a senior military commander (daisho),

had the third rank.

In the middle of the Heian era , a daisho,

as a rule, was also a minister or an adviser to a minister

(dainagon

or

chunagon).

Subordinate to the senior military commander was the second military commander (chujo). Chujo

had, as a rule, the Fourth rank and at the same time could be appointed state councilor

(saisho no chujo)

or chief archivist

(to no chujo).

The Imperial Personal Guard usually consisted of two or four military leaders.

Junior military leaders (shosho)

were appointed from among persons of the Fifth Rank.

Often they also served in the Audit Office (ben no shosho)

or in the Imperial Archives

(kurodo no shosho).

The Imperial Personal Guard usually consisted of four junior military leaders.

Warlords (daisho, chujo

and

shosho)

usually accompanied the emperor on trips and during especially solemn ceremonies with a bow and arrow in their hands.

Senior guards (shogenjo)

or

dzo)

were constantly with the imperial person.

They usually held the Sixth Rank and served simultaneously in the Imperial Archives (Kurodo no Zō). [64]

Six guard services (Table 3)

[65] Junior guards (shoso) and

servants

(toneri)

performed various simple duties during rituals and ceremonies; they formed the guards of the imperial palace, and they also made daily night rounds.

2. Left and Right gate guards (Saemonfu, Uemonfu) -

in contrast to the Personal Imperial Guard, which directly guarded the imperial chambers, they controlled the external approaches to the imperial palace.

Head of the gate guard (emon no kami)

a person of the Fourth Rank was appointed, often also holding the title of Ministerial Advisor or State Advisor.

The assistant (emon no suke)

and guards

(zo, sakan).

Zo Guard

He was also called

yugei no tsukasa

(quiver-carrying), because he usually had a bow in his hands and a quiver of arrows behind his back.

3. Left and Right palace guards (sahoefu, uhoefu)

guarded the gates of the imperial palace, monitored order in the palace, and accompanied members of the imperial family during ceremonial trips.

The ranks are the same as in the Gate Guard.

Imperial Archives (Kurodokoro, plate 4)

The imperial archive was not provided for by the Taihoryo code; it was established at the beginning of the 9th century. Initially, the servants of the Imperial Archives were in charge of the most valuable manuscripts and imperial rescripts, but very soon he began to be in charge of all palace affairs. Archivists (kurodo)

They were always in the emperor’s chambers, conveying his instructions, and managing ceremonies. The emperor's wardrobe and table gradually came under their control. Young men from noble families were usually appointed archivists; for many, this position became the beginning of a court career. (All the most powerful persons from the Fujiwara family - Michitaka, Koretika, Michinaga - began their court service from the Imperial Archives.)

Head of the Imperial Archives (batto)

a person of the Second Rank was appointed, usually a left or right minister, less often a senior adviser to the minister

(dainagon).

Under the head of the archive (a purely nominal position) there were two chief archivists (kurodo no go),

in charge of various aspects of palace life.

They were appointed from persons of the Fourth Rank, and, as a rule, one of them served simultaneously in the Audit Office (to no ben),

and the second in the personal imperial guard

(go no chujo).

At the disposal of the chief archivists were three guardians of the Fifth Rank (goi no kurodo)

and four guardians of the Sixth Rank

(rokui no kurodo),

who carried out minor tasks for the emperor and served the three highest meals.

Guardians often served in the Imperial Personal Guard (Konoefu)

or the Gate Guard

(Emonfu).

Imperial workshops (Surisiki, table 5)

[66]

The imperial workshops were engaged in the repair and production of utensils for the imperial palace.

An institution not covered by the Taihoryo Code. The head of the workshops (daibu)

had the Fourth rank.

Rear (women's) chambers of the palace (Kokyu, table 6)

The Taihoryo Code provided for the presence of a certain number of concubines of different categories in the women's quarters of the palace.

Concubines of the highest category (next in importance to empresses) (hee)

- two.

The hees

were chosen among the princesses of the blood.

Middle category concubines (fujin)

- three.

Fujin

were chosen from among the daughters of nobles of the Third Rank.

Concubines of the lowest category (hime)

- four.

Hime

were chosen from among the daughters of officials of at least the Fifth Rank.

At the end of the 8th - beginning of the 9th century. a new title arose - the highest concubine (nyogo),

which replaced all the previous ones.

At first, nyo

were chosen among the daughters of courtiers of relatively low rank (Fourth or Fifth) and, in essence, were no different from

hime,

but by the end of the 9th century.

his

authority increased significantly, they began to be chosen among the daughters of nobles no lower than the Third Rank (as a rule, they were princesses of the blood or daughters of princes of the blood, great ministers).

Under favorable circumstances (most often in the presence of a powerful patron in the person of a father, brother or uncle), she

could become an empress consort (especially if she had a son).

[67]

Rear (women's) chambers of the palace (Kokyu, plate 6)

[68]

The next most important title after

him

was the title of dress changer

(koi).

Initially,

they

managed the emperor’s wardrobe and carried out his small assignments; later they began to serve in his bedchamber, taking the position next to him in the women’s chambers.

Koi

were chosen from among the daughters of ministerial advisers of the Fourth Rank and below.

Nyogo or koi,

having children or enjoying the special favor of the emperor, they were usually called servants of the imperial bedchamber

(miyasudokoro),

and the concubines of the crown prince were also called.

Myobu is a common name for ladies of the Fourth or Fifth Rank.

From the concubines of the nyeo

the empress consort

(chugu) was chosen.

In addition to the empress consort, there was also the empress mother

(kotaigo)

- the mother of the reigning emperor and the great empress mother

(taikotaigo)

- the mother of the previous emperor.

Originally, the empress consort was called kogo,

and the word

chugu

(middle chambers) denoted all three empresses.

The Taihoryo Code provided for the Middle Chamber Service (Chugushiki),

which dealt with the affairs of all three empresses.

However, under Emperor Ichijo (991–1010), regent Fujiwara Michinaga managed to achieve the title of empress consort for his daughter Shoshi, ignoring the fact that there was already one empress consort under the emperor. As a result, Teishi, retaining the title of kogo,

left the palace, and Shoshi reigned in the imperial chambers, receiving the new title of

chyugu.

Since then, the wife of the reigning emperor began to be called

chyugu,

and the wife of the abdicated emperor -

kog.

Imperial concubines and empresses were served by court ladies (palate).

There were three categories of court ladies - the highest

(joro),

middle

(tyuro)

and lowest

(gero).

The same name was given to ladies who were in the service of the daughter or wife of a noble dignitary.

One of the most revered female court titles was that of Guardian of the Highest Casket (mikushigedono no betto).

The keeper of the Highest Casket headed the workshops located in the chambers of the Highest Casket of the Joganden Palace, where the outfits of the imperial family were sewn and stored.

This title was received, as a rule, by court ladies (palate)

of the highest ranks.

Sometimes girls from noble families entered the service of the palace as guardians of the Highest Casket, and after a while they were awarded the title of it.

The Taihoryo Code provided for twelve services that were in charge of various aspects of the life of the women's quarters.

The most important among them was the Department of Palace Maids (naishi no tsukasa).

The ladies who were part of it served in the highest chambers, conveyed the orders of the emperor, carried out his instructions, trained and supervised the maids, accompanied the empresses on trips, and monitored the observance of the rules of etiquette in the women's chambers.

At the head of the Department were two main managers (naishi no kami),

who were chosen from among the daughters of dignitaries of the Third Rank, often the daughters of great ministers were appointed to this position.

[69]

Naishi no kami

They were constantly in the imperial chambers and conveyed the emperor’s instructions to the rest of the servants.

Naishi no kami was subordinate to four stewards (naishi no suke)

and four junior stewards

(naishi no jo),

who were chosen from among the daughters of officials of the Fourth and Fifth ranks, respectively.

In addition to the stewards, there were about a hundred attendants (nyoju) in the Palace Maid Department.

Local authorities

Each province (and there were 74 of them in ancient Japan) was appointed by a ruler (kami)

for a period of four years.

Provinces were divided into categories (Daikoku, Jokoku, Chugoku

and

gekoku).

The most profitable appointment was considered to be

the daikoku

- the great provinces.

In the provinces of Hitachi, Kazusa, and Kozuke, only princes of the blood were appointed rulers. An appointment to a lower-ranking province, gekoku, was considered unfavorable for a career.

Often the rulers themselves did not travel to the provinces and, remaining in the capital, sent their assistants (suke) there.

Rulers who left the capital and settled in their province were called governors (zuryo).

The governors gradually became a significant force on the ground, rallying the local nobility around them.

Control over local authorities was exercised by special overseers (azechi),

subordinate to the State Council.

(azechi no, dainagon, azechi no chunagon),

the Office of the Western Lands (Dazaifu) were appointed to it.

(Table 7) was in charge of the provinces on the island of Tsukushi (modern Kyushu) and the small islands adjacent to it.

Dazaifu's responsibilities included guarding these lands, collecting taxes from the local population, maintaining diplomatic relations with their western neighbors, and controlling private estates and monasteries. head of the administration (soti)

.

If the head of the Office was a prince of the blood, then his duties were performed either by a deputy (gon-no soti),

or a senior manager

(daini),

appointed from among the officials of the Fifth Rank.

Gon no sochi

and

daini

are interchangeable positions.

gon no sochi daini

was present in Dazaifu, it was absent, and vice versa.

Local residents were appointed to lower positions (daigen, shogen)

Clergy

Already at the beginning of the 7th century. The secular authorities made an attempt to restore order among the clergy by distributing them according to a hierarchical principle.

The highest spiritual rank became the san sojo,

in meaning corresponding to the Second Rank of a courtier.

[70]

daisojo and sojo arose

and

gon-sojo.

Sozu - san next to sojo

(later

Daisozu arose. Gon-Daisozu, Shosozu, Gon-Shosozu).

Corresponded to the Fifth Rank of a courtier.

Rissi is the youngest of the three major clergy, corresponding to the Fifth Rank. Rissi's duties

included the taking of vows by those entering monasticism.

Zasu - initially the abbot of any monastery; later only the abbots of the Enryakuji Monastery on Mount Hie (Tendai sect) began to be called this way.

Hijiri was the name given to hermit monks who lived outside the monastery in huts.

Azari (Sanskrit akarya)

- a monk of the highest class who has disciples.

In importance in the hierarchical system it followed rissi .

The text is reproduced from the edition: Murasaki-shikibu. The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari). Application. M. Science. 1992

© text - Sokolova-Delyusina T. L. 1992 © network version - Thietmar. 2013 © OCR - Nikolaeva E. V. 2013 © design - Voitekhovich A. 2001 © Science. 1992

References

- Encyclopedia Britannica

. - ^ a b

Print. - Shively and McCullough, 1999.

- Ancient Japan

. - Hirst 2007 p. 32

- Takei and Keen 2001 p. 10.

- Hirst 2007 p. 34.

- Hirst 2007 p. 35.

- Meyer P. 44.

- Friday 1988, pp. 155–170.

- Kitagawa 1966 p. 60.

- Kitagawa 1966 p. 61.

- Kitagawa 1966 p. 65.

- Weinstein 1999.

- Kitagawa 1966 p. 59.

- Morris 1964, p. 180, 182.

- Morris, 1964, p. 183–184.

- Morris 1964 p. xiv.

- Toby 2009 p. 31.

- ^ a b

Morris 1964 p. 73. - Morris 1964 p. 79.

- ^ a b

Collins 1997 p. 851. - Ponsonby-Fein, 1962, pp. 203–204; also known as Fujiwara jidai

. - Britannica Kokusai Dai-Hyakkajiten

. - Ponsonby-Fein 1962 p. 204.

- Fallingstar 2009.

- Fallingstar 2011.

Modern images

The iconography of the Heian period is widely known in Japan and is depicted in a variety of media, from traditional festivals to anime. In the manga and series Hikaru no Go, the main character Hikaru Shindo is visited by the ghost of a Heian period genius and his leading clan, Fujiwara no Sai.

Various festivals feature Heian clothing, most notably the Hinamatsuri (doll festival) where dolls wear Heian dress, as well as many other festivals such as the Aoi Matsuri in Kyoto (May) and the Sayo Matsuri in Meiwa, Mie (June). both of which include the Unihito 12-layer dress. Traditional mounted archery (yabusame) festivals that have been held since the beginning of the Kamakura period (immediately after the Heian period) have similar clothing.

Literature

Two-volume historical saga novel White as Bone, Red as Blood: The Fox Sorceress

(2009),[26] and

White as Bone, Red as Blood: God of the Storm

(2011)[27] detail the pivotal years 1160–1185 in Japan through the eyes of protagonist Seiko Fujiwara. Both books were written by Cerridwen Fallingstar.

Games

Game Total War: Shogun 2

has

Rise of the Samurai

expansion pack in the form of a downloadable campaign. It allows the player to create their own version of the Genpei War that happened during the Heian period. The player can choose one of the most powerful families of Japan at that time - Taira, Minamoto or Fujiwara; each family has two branches, for a total of six gaming clans. The expansion pack includes a different set of land units, ships and buildings, and is also available in multiplayer modes.

Cosmology of Kyoto

is a Japanese video game set in Japan during the 10th and 11th centuries. It is a point-and-click adventure game depicting Heian-kyo, including the religious beliefs, folklore, and ghost stories of the time. Film critic Roger Ebert praised it.