Every person who was once interested in learning the Japanese language faces a difficult task - to learn at least 2136 characters, which in Japan are called kanji. Why 2136? This is the number of kanji chosen by the Japanese Ministry of Education for its citizens to study. Every Japanese takes an exam on their knowledge upon graduation from school. If you want to achieve even a small understanding of the Japanese language, you need to know at least 1000, but this still seems an insurmountable obstacle, because hieroglyphs seem much more complex than letter words.

In fact, the process of learning kanji can be very simple if approached correctly. Let’s say right away that reading one hieroglyph 100 times a day and hoping that you can remember it this way is not at all the most effective method of learning. The methods described here are based on techniques used by world memory champions and on the work of philosopher and Japanese scholar James Heisig, author of the book Remembering the Kanji, which is one of the most famous ways of learning kanji since 1977 in the English-speaking world, but does not have a Russian version . Let's first look at a few kaji to understand what we're dealing with.

Keys

Originally, kanji were meant to be ordinary drawings representing the object they point to. For example, kaji 人 means “person,” kanji 火 means “fire,” and kanji 山 means “mountain.” A few kanji have indeed retained their historical meaning and one can guess their meaning by their writing, but unfortunately most of them do not fall into this category. Fortunately, more complex kanji are made up of simple kanji and we can memorize their combination. For example, the kanji 町 (village, small town) consists of two elements: the kanji 田 (rice field) and the kanji 丁 (street). Each kanji in the Japanese language either exists on its own (there are about 200 of them) or consists of several elements.

Hieroglyph structure

At first glance, the hieroglyph seems to be a chaotic collection of various lines and dots. However, it is not. There are several basic elements that make up a hieroglyph. First of all, these are the features that make up graphemes. Graphemes, in turn, form a more complex sign.

♦ On the subject: Gateway to Calligraphy: Eight Principles of Writing the Character Yun 永

Traits

Any hieroglyph consists of a certain set of features. The traits themselves have no lexical meaning or reading. There are four types of traits and more than two dozen varieties:

- Simple (basic) features: horizontal, vertical, inclined left and right, folding left and right, special points.

- Features with a hook: horizontal, vertical (can be with a hook to the left or a hook to the right), folding to the right.

- Broken features: the line changes direction one or more times, has a complex configuration.

- Broken features with a hook.

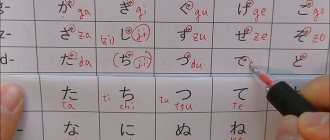

There are also slightly different classifications of traits, but this does not change the general essence. The lines in hieroglyphs are written in a strictly defined sequence: “first horizontal, then vertical, first folding to the left, then folding to the right, first upper, then lower, first left, then right, first in the middle, then on both sides of it, first we go inside , then we close the door.”

In the past, hieroglyphs consisted of a large number of strokes, and remembering them was not easy. Therefore, one of the goals of the writing reform carried out by the Chinese government in the 60s of the 20th century was to simplify the characters by reducing the number of strokes.

A similar simplification of hieroglyphs was carried out in Japan. However, simplified Japanese characters do not always correspond to Chinese ones, although knowing the full and simplified versions of Chinese characters, it is usually easy to understand the simplified Japanese ones. For example, the word "library" written in Simplified Chinese: 图书馆, Long Chinese: 圖書館, and Japanese: 図書館. In Chinese it is read túshūguǎn, in Japanese - toshokan.

In Taiwan, Singapore and some other places, the full version of writing hieroglyphs is still used. And in mainland China you can find texts written in full hieroglyphs. In addition, hieroglyphs with several dozen features have survived to this day. As a rule, they are rarely used and therefore have not been simplified.

The most difficult character to write is considered to be biáng (byang), which consists of more than 60 strokes. It refers to a type of noodle popular in Shaanxi Province. Outside the region, this hieroglyph is practically not used, and therefore it is absent from dictionaries and computer fonts.

The hieroglyph "byan" is considered the most difficult to write. They say that students at one of the institutes in Chengdu were systematically late for classes. And the professor, angry with them, ordered everyone to write the hieroglyph “byan” a thousand times. Not everyone was able to do this. And everyone tearfully asked for forgiveness, promising not to be late for classes in the future.

Graphemes and clues

Graphemes are formed from traits - simple hieroglyphic signs with stable lexical meanings. These are the basic characters of Chinese hieroglyphic writing that make up Chinese characters. They are the most ancient and express the basic elements of the surrounding world and man.

Examples of graphemes: man 人 rén, woman 女 nǚ, child 子 zǐ, sun 日 rì, sky 天 tiān, earth (soil) 土 tǔ, etc.

♦ Read more about the history of Chinese writing and the PRC reform to simplify hieroglyphs in the article “Chinese characters from antiquity to the present day.”

There are about 300 graphemes in total; linguists differ in their estimates regarding their exact number. Most graphemes are used in modern Chinese writing as the most common characters. Graphemes make up about 10% of the most commonly used hieroglyphs.

In addition to graphemes, there are keys . Keys are the main classification marks. The standard list of keys contains 214 characters. It includes many graphemes and some features that do not have a fixed meaning. Thus, not all graphemes are keys and not all keys are graphemes.

For a long time, a list of 214 keys constituted the so-called hieroglyphic index, according to which hieroglyphs were ordered in Chinese dictionaries. However, after simplified hieroglyphic writing was introduced into the PRC, some characters underwent either partial simplification or structural changes.

For students of languages with hieroglyphic writing, knowledge of the key table is mandatory.

Complex signs

Most hieroglyphs consist of two or more graphemes. Traditionally, they are divided into two large groups: ideographic signs and phonideographic signs.

Ideographic signs

Ideographic signs (ideograms) consist of two or more graphemes. In them, the meaning of the hieroglyph is derived from the semantics of the graphemes included in it, but the reading of the hieroglyph is in no way connected with them. In modern Chinese, the share of ideographic signs is about 10%.

Examples of ideograms:

- 好 hǎo (good): 女 nǚ (woman) and 子 zǐ (child)

- 明 míng (understanding, enlightenment): 日 rì (sun) and 月 yuè (moon)

- 休 xiū (rest): 人 rén (person) and 木 mù (tree)

- 众 zhòng (crowd): three people 人 rén

- 森 sēn (forest, thicket, dense): three trees 木 mù

Phonoideographic signs

About 80% of hieroglyphs are so-called phonideographic signs, or phonideograms. Hieroglyphs of this type usually consist of two parts. One part is called the semantic factor , or hieroglyphic key . It indicates that the hieroglyph belongs to a certain group of semantically related characters and thereby suggests an approximate meaning.

The other part of the hieroglyph is called the phonetic and suggests an approximate reading. After the reform of Chinese writing, the number of phonideograms consisting of two graphemes increased significantly, which greatly facilitated the memorization of hieroglyphs.

Examples of phonoidograms:

- 妈 mā (mother): 女 nǚ (woman - key) and 马 mǎ (horse - phonetician)

- 性 xìng (nature, character, gender): 心 xīn (heart, consciousness - key) and 生 shēng (birth - phonetician)

- 河 hé (river): 水 shuǐ (water, in the hieroglyph “river” the element “water” in the left position changes to a flap with two dots - key) and 可 kě (modal verb of possibility or obligation - phonetic)

However, in the process of development, the reading of many hieroglyphs has changed and nowadays it is not always possible to guess even the approximate reading of a hieroglyph. Especially when it comes to dialects of the Chinese language.

Memory technique

Understanding the keys already makes the task a lot easier, but to find an effective method for studying them we need to repeat a little of what we know about human memory. What do we do when we try to remember something? We believe that to memorize, you just need to periodically repeat the learned material. This is true, but when we need to learn and not confuse 2136 incomprehensible squiggles, this method quickly becomes another problem. Kanjiway uses several different memory techniques to help you retain information more easily. Let's return to the kanji 町. Instead of just trying to remember the equation “rice field + street = village,” we can use our visual memory and create a story that will help us reproduce the kanji elements in our head. Imagine that you are walking down a STREET and come across a large RICE FIELD where people from the nearest VILLAGE are working. Right now, try spending 5 seconds replaying this scene in your mind, rather than just reading a sentence in this article. The next time you come across the kanji 町 you will see two constituent elements and you will immediately remember this story, which will help you quickly get to the very meaning of the kanji. Here's another example: 則 (law, rule, rule) consists of 貝 (shell/clam) and 刂 (sword). We can imagine a MOLLUSK who came to the village with a huge SWORD, overthrew the government and began to establish his own RULES/LAWS.

When coming up with different stories and scenes for memorizing kanji, try to be based on the following principles:

- The story must be greatly exaggerated. Instead of imagining an ordinary clam, you can imagine a huge tyrant clam with a giant sword in his hand. The weirder and funnier the story, the better.

- The story should contain small details that will help you remember the story itself. You can imagine screaming defenseless children looking in fear at their new ruler - a tyrant clam.

- When you imagine a story in your head, try to additionally involve other senses, such as touch, smell, sound. To this image you can add the screams of women who are enslaved by a new tyrant mollusk, you can imagine how you yourself are in the village and smell the tyrant mollusk a few meters away, and so on.

You will probably say that this is very stupid, but the strength of this technique lies precisely in its apparent frivolity. It is much easier for people to remember things that evoke some kind of emotion in them, even the most minimal, and even if this emotion is “Oh my God, how stupid this is.” These are the methods that people who compete in memory championships use in their practice; with their help, a person can remember 100 random numbers in a row, the order of cards in a deck, or a speech that needs to be delivered on stage.

Information + emotion = memory

This technique allows us to memorize kanji much faster, but the kanji will still need to be repeated, otherwise you will forget them in a couple of weeks.

Features of the Japanese language for children

When teaching children, classes are conducted in a playful way. The work uses colorful manuals, songs, poems, fairy tales, and interactive video programs. Children participate in theatrical performances.

The child is introduced to the history of the country, culture, and national characteristics. During training, thanks to a special alphabet and the logic of constructing sentences, memory, thinking, and imagination develop. At the same time, native speech improves and hearing develops. Children get acquainted with the sound diversity of the world. Their research interest is awakened. For many children, Japanese calligraphy later turns into a hobby.

Repetitions

At school we are told to learn words this way: read the word 10 times and “just remember it.” Nobody explains exactly how to remember a word, so most often we blame ourselves for not being able to remember new vocabulary as quickly as we would like. This cramming method may work, but it is one of the most ineffective ways to learn a language. By repeating a word N times and simply relying on our memory, we do not take into account the fact that the first two hours after reading we remember this word well, but we will not remember it the next day, much less in a week or a month. Kanjiway solves this problem with its spaced repetition system. This is a very simple but powerful concept that allows us to learn not only foreign languages, but also any information that we would like to remember. Instead of trying to repeat words ourselves when it seems necessary to us, an algorithm works for you that distributes repetition dates many days in advance. Let's say today you learned a new kanji and would like to remember it. Kanjiway automatically chooses a time when it's useful for you to repeat it next time, based on data such as the difficulty of that kanji, the number of repetitions completed, the time it takes to recall the kanji, your learning progress, and so on. This way, you don't have to keep in mind which of the 2136 kanji you need to repeat at what point. Kanjiway every day and you will always have that list of kanji that you need to repeat today, specially optimized for your path of learning kanji.

Easy ways to remember writing hieroglyphs

I think you are convinced that the hieroglyph has a clear structure and cannot contain random elements. This makes it quite easy to remember the spelling and meaning of hieroglyphs.

Graphemes go back to pictograms, representing modified, extremely simplified and abstract drawings. On the Internet you can find many pictures showing how the image gradually became more abstract and abstract. This helps with quick memorization.

The most ancient hieroglyphs, from which modern ones are derived, date back to the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. These are Yin fortune-telling inscriptions on animal bones and turtle shells. Gradually, the images became more and more abstract until they acquired the modern spelling

- 人 rén person: two legs and a body

- 大 dà big: a man has his arms outstretched

- 天 tiān sky: something big over a big man (option: One over a big man)

- 山 shān mountain: three peaks

- 口 kǒu mouth: keep your mouth wider

- 曰 yuē say: tongue in mouth

- 竹 zhú bamboo: resembles two bamboos

When I first started studying Chinese at university, we first studied a list of 214 keys. I wrote them down many times, trying to write beautifully and remember the correct order of features, which is strictly fixed. This is not worth wasting your time on.

Having studied the keys, it is not difficult to remember complex signs - ideograms and phonideograms. You can come up with a story that will allow you to forever remember complete hieroglyphs with a large number of features.

Memorization examples:

- 妈 mā mother - a woman 女 nǚ who works like a horse 马 mǎ

- 好 hǎo good - when a woman 女 nǚ gives birth to a child 子 zǐ

- 江 jiāng river - water 水 shuǐ that does the work 工 gōng (the character for "river" is an example of a phonoid ideogram where the phonetic reading of "work" has changed over time)

- 仙 xiān saint, immortal - a person 人 rén who lives in the mountains 山 shān

- 怕 pà to be afraid - the heart 心 xīn turned white 白 bái from fear

- 休 xiū rest - a man 人 rén lay down to rest under a tree 木 mù

- 难 nán difficult – difficult with the right hand (again) 又 yòu to catch a short-tailed bird 隹 zhuī

- 国 guó state - ruler with a spear 玉 yù (jade, symbol of imperial power) behind the fence 囗 (without reading).

The main thing is to give free rein to your imagination. Over time, this will become a habit and to memorize a hieroglyph it will be enough to simply remember the names of the graphemes that make up its composition.

And here is an example of memorizing the full spelling of the character “love” 愛 ài. If you break it down into its component elements, add a little humor, you get the following phrase: “the claws sank into the heart, the legs gave way, and then the lid came.”

Or here's how you can remember the hieroglyph 腻 nì. Its dictionary meanings are “grease, dirt, shiny, glossy, smooth.” It consists of the graphemes “moon” (very similar to it is “meat”), “shell”, “archery” and “two”. You can come up with a story: a man shot game with a bow (glossy meat, fatty, shiny, with a lot of fat), and sold it for two shells (in ancient times - money) to the Japanese. Just in Japanese, “two” is read no matter what.

The funnier and more absurd the story, the easier you will remember the hieroglyphs.

In addition, very often such an analysis of hieroglyphs helps to further clarify the meaning of the most complex and polysemantic categories of Chinese philosophy and culture. In my lectures on Chinese philosophy, I often resort to this method of explanation.

Take, for example, the category “dao” 道 dào . Tao is one of the key categories of Chinese philosophy and culture, very multi-valued and complex. I will list its main dictionary meanings:

- way, road, tract; track, road; on the way, on the way

- path, route; tract; astr. path of a celestial body, orbit; anat., med. tract

- paths, direction of activity; way, way, method; an approach; means; rule, custom

- technology, art; trick, cunning; trick

- idea, thought; teaching; doctrine; dogma

- reason, basis; rightness; truth, truth

- Philosopher Tao, true path, highest principle, perfection

- Taoism, the teachings of Taoists; Taoist monk, Taoist

- Buddhist teaching.

And these are not all the meanings! However, if you break the hieroglyph into its constituent graphemes, then all the meanings will become intuitively clear. The first grapheme is 首 shǒu, “head, crown, beginning, main, main, essence.” The second is “move forward.” That is, Tao is something basic that moves forward, is in motion.

Or, another example, the most important Confucian category仁 rén is philanthropy, humanity . The hieroglyph consists of two graphemes: man 人 rén and two 二 èr. And it is read the same way as “man”. That is, philanthropy is relationships between people that are built on the basis of justice. As Confucius said, “Only those who love humanity can love people and hate people” (“Lun Yu”, IV, 3).

♦ On the subject: How to learn hieroglyphs and replenish your hieroglyphic stock?

One of the favorite pastimes of the Chinese is to write characters with a brush dipped in water. Moreover, here the hieroglyphs are also written in a mirror image!

Order

In addition to all of the above, we can say that it would be a good idea to not just learn kanji in random order, but to arrange them in the order that will be most effective for you. Kanjiway uses the following principles when choosing which kanji you need to learn next:

- We're basing this on how popular the kanji itself is in the Japanese language. You will be much better off learning the most common kanji first, such as "money", "today", "food", rather than the rarer ones, such as "power plant", "princess", "bamboo tree".

- We look at the kanji you have already learned and your progress in memorizing and repeating them, the following kanji will be selected specifically to make it easier for you to learn them.

- We look at what kanji are taught in Japanese schools and in what grades. We will try to make your learning path similar to what the Japanese themselves go through when learning kanji.

A proven way not to get confused when reading a hieroglyph

The last important topic to cover is vocabulary. It is necessary to inextricably study vocabulary and hieroglyphs.

The above rules may seem very complex and inconsistent to you. And indeed, if you study hieroglyphs alone, it will be quite difficult, when faced with a hieroglyph in the text, to guess with 100% probability how it will be read. On the other hand, studying and knowing Japanese vocabulary can be a very good help in this. For example, first from the general Japanese language course you will learn that there is a word for “adult”, otona. Later, when studying the hieroglyphs “big” and “man”, you will come across the fact that otona is written as “big man” (大人), and this spelling will become something natural and self-evident for you.

Kun and onn reading may seem like a complex system, but the general rule remains that in the vast majority of cases a single hieroglyph will be read according to kun reading, and hieroglyphic combinations of 2 or more hieroglyphs will be read according to on.

Readings

The final challenge to learning kanji that we will touch on in this article is that kanji usually have several different readings (or pronunciations). Historically, kanji came to Japan from China, but the Japanese at that time already had their own language. Therefore, it turned out that many kanji have a pronunciation that remains from the Chinese language - “on'yomi” and the Japanese pronunciation - “kun'yomi”. Japanese people use both pronunciations in everyday speech. A very common mistake that people make at the beginning of their language learning journey is that they try to learn both the meaning of kanji and their reading at the same time. If a person tries to learn kanji in this way, then as a rule he overloads himself with information and learning Japanese turns from an interesting process into torture. Let's imagine for a moment that we are learning Russian and we need to learn the symbol “1”. If you are simultaneously learning the meaning of a symbol and its reading, then you need to immediately remember that “1” is read as “one”, “one”, “first” (1st, 1st) and so on. The same with “2”: “two”, “dv”, “second”. Even if you can remember 10 digits this way, don't think it will work well with 2000+ kanji.

You can learn reading immediately when studying a European language such as English, Spanish, French or even Russian, because their words consist of letters that can be simply read and there is no strong need to memorize them. In the case of kanji, it is almost impossible to understand the reading of a character by its writing. We recommend dividing the study of the meanings and readings of kanji into different stages. First, start studying the meanings of kanji, at least 500 or 1000. This way you can look at a sentence from the Japanese language and roughly understand what is being said, without knowing exactly how to read it. After that, start learning the words, which will be much easier for you, because you already know the meanings of the kanji from which this word consists. While learning words, you will be able to automatically learn their pronunciation without spending a lot of time on it.

What about onon or kun? Basic reading rules.

So is it according to him or according to kun?

One way or another, for people studying Japanese, the question remains a great intrigue and mystery: how can I still read the hieroglyphs that I see in the text - by onon or by kun?

Let's look at the basic rules about kun and on reading.

1) Hieroglyphic combinations consisting of 2 or more hieroglyphs are usually read according to onny, Chinese readings:

先生 (sensei) - teacher

日本人 (nihonjin) - Japanese

自動車 (jidousha) - car

2) A separate hieroglyph (that is, there will be hiragana or other words to the right and left of it) is read according to kun, Japanese readings:

生ける (ikeru) - to do ikebana

あの人 (anohito) - he, she

車 (kuruma) - car

Separately, a stylistic difference should be noted: the words of Chineseisms (in fact, words read according to onic readings) sound more formal, scientific, official, dry. They are widely and often used in scientific literature, official documents, contracts, public speeches by politicians, and news. Words of Japanese origin are more typical of ordinary everyday speech and sound simpler and more down-to-earth. Thus, the words 車 (kuruma), a car, will be used more in a domestic context, and the word 自動車 (jidousha), a car, will be used when talking about a car plant or production volumes.

Unfortunately, the above rule only works in 80-90% of cases, and in Japanese the opposite situation can be observed:

3) There are free-standing characters that will be read, no matter what, in Chinese, even if they have Japanese readings:

本 (hon) - book

絵 (e) - picture

円 (en) - yen

About combinations:

4) There are hieroglyphic combinations that will be read according to Kun, Japanese, reading:

父親 (chichioya) - father

白黒 (shirokuro) - black and white

旅人 (tabibito) - traveler*

*In this word we also observe voicing of the initial consonant of the second root (hito → bito), which is characteristic of Japanese root formation, but, unfortunately, there is no single rule for this phenomenon; in some cases voicing occurs, but in others it does not. You can remember this only together with learning vocabulary.

5) There are hieroglyphic combinations in which part of the hieroglyphs will be read according to on, and the other part according to kun:

半年 (hantoshi) – six months

目茶 (mecha) - absurdity, absurdity

日曜日 (nichiyoubi) - Sunday

At the same time, sometimes the onn reading is in first place, and the kun reading is in second, while in other combinations we see the opposite situation. Particularly noteworthy is the last word 日曜日 (nichiyoubi), "Sunday", since in it the character 日, meaning "sun, day", is repeated twice, the first time being read as "nichi", and the second as "bi" . Where is the logic? - you ask. And you’ll be right, because it simply doesn’t exist. It is for this reason that when studying hieroglyphs, it is necessary to pay attention not only to the list of on and kun readings, but also to the combinations in which this hieroglyph is used.

6) In addition to the above, there is a special category of readings of hieroglyphic combinations, which is called ateji (当て字). Ateji arose due to the fact that some native Japanese words began to be written not with one, but with two hieroglyphs, for example:

今日 (kyou) - today

大人 (otona) - adult

一人 (hitori) – 1 person

Usually in textbooks on hieroglyphs such combinations, read in a non-standard way, are also written out and marked separately as exception words.

7) And finally, there is a special category of hieroglyphs called kokuji (国字), literally translated as “signs of the native country.” These are the hieroglyphs that were invented by the Japanese themselves, so such hieroglyphs do not have Chinese readings. They will be read only according to kun:

畑 (hatake) - vegetable garden

峠 (tooge) - mountain pass

込む (komu) - to be crowded

How long does it take to learn kanji?

We touched on the main technical problems that people face when learning kanji. That being said, the biggest problem is that learning kanji is a lot of work. Japanese is rightfully considered one of the most difficult languages to learn. Even if you learn 50 kanji per day, which is already a lot, it will take you at least 42 days to learn all 2136 kanji. In this case, you need to correctly calculate your strength so as not to abandon the learning process after a couple of weeks, which, unfortunately, happens quite often, but only if you begin to overload yourself with information. Kanjiway uses , such as memorization techniques, creating your own markers and stories, and a spaced repetition system, make learning kanji a fun and enjoyable experience without you having to waste your time trying to figure out which kanji you need to learn or repeat and in what order to do it. In addition to studying Japanese, we almost always go to work or study and mind our own business. Try to work at your own pace and if you feel that you are starting to get tired, then slow it down a little. There is absolutely no reason why you should learn exactly 20, 50 or 100 kanji per day, so don't force yourself to work towards the dates and deadlines you set when you decided to study Japanese. If you are interested in specific numbers, then learn at least 50 kanji in order to understand at least a little what this process consists of, choose the approximate number of kanji that you would be comfortable learning per day and divide the number 2136 by yours.

Learning Japanese is a marathon, not a sprint

Recommendations for beginners

To take your first steps in learning a language, you should adhere to the following recommendations:

- Set a goal - why you are learning the language.

- Exercise regularly. It's better to do it a little often than rarely and for a long time.

- Learn syllabic alphabet. First you need to learn 92 katakana and hiragana characters.

- Do not set the option to remember all hieroglyphs (5000) at once. Even the Japanese learn kanji throughout their lives. To study, it is worth using proven memorization techniques. To understand the language, only 1000 characters are enough, and to pass the test at a high level – 1500-2000 characters.

- Practice your pronunciation regularly.

- Constantly expand your vocabulary. This should be done in parallel with practicing pronunciation.

- Make contact with others who are at the same stage of learning Japanese. Communication on sites will help you stay motivated, receive valuable advice, and avoid common mistakes.

- Immerse yourself in the environment. The language environment - media, books, films, music, anime - should be everywhere.

- Study the history and culture of Japan.

Many Japanese schools offer language tours. Winning competitions can provide this opportunity for free.

Is knowing only 2136 kanji enough?

2136 joyo kanji is enough for you to know the Japanese language very well and pass the last stage of the official Japanese language proficiency exam, but the Japanese themselves usually know more. If, after learning basic kanji, you want to understand the language even better and understand it more, then it is advisable to increase your knowledge to about 3000 kanji, which Kanjiway will also help you with. Since by this point you'll likely have a good grasp of all Japanese, not just kanji, this will be even easier.

- There is also another pronunciation - "nanori", it is mainly used in people's names, but try not to think about it for now. When starting to learn Japanese, it is better to concentrate your efforts elsewhere.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Tuesday, June 17, 2008 16:02 + in quotation book Kanji (Japanese: 漢字 (i)) are Chinese characters used in modern Japanese writing along with hiragana, katakana, Arabic numerals and romaji (Latin alphabet). History The Japanese term kanji (漢字) literally means "Letters of the (Han Dynasty)". It is not known exactly how Chinese characters came to Japan, but today the generally accepted version is that Chinese texts were first brought to the country by Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje in the 5th century. n. e.. These texts were written in Chinese, and so that the Japanese could read them using diacritics while observing the rules of Japanese grammar, the kambun (漢文) system was created. The Japanese language at that time did not have a written form. To record native Japanese words, the Man'yōgan writing system was created, the first literary monument of which was the ancient poetic anthology Man'yōshu. The words in it were written in Chinese characters according to their sound, not their meaning. Man'yogana, written in cursive script, evolved into hiragana, a writing system for women for whom higher education was not available. Most of the literary works of the Heian era with female authorship were written in hiragana. Katakana arose in parallel: monastery students simplified man'yogana to a single meaningful element. Both of these writing systems, hiragana and katakana, derived from Chinese characters, later developed into syllabaries, collectively called kana. In modern Japanese, kanji are used to write the stems of nouns, adjectives and verbs, while hiragana is used to write inflections and endings of verbs and adjectives (see okurigana), particles and words whose characters are difficult to remember. Katakana is used to write onomatopoeia and gairago (loan words). Katakana began to be used to write borrowed words relatively recently: before the Second World War, usually, borrowed words were written in kanji, either by the meaning of the characters (煙草 or 莨 tabako = “tobacco”), or by their phonetic sound (天婦羅 or 天麩羅 tempura) . The second use is called ateji. Japanese additions Initially, Kanji and Chinese Hanzi were no different from each other: Chinese characters were used to write Japanese text. However, nowadays there is a significant difference between Hanzi and Kanji: some characters were created in Japan itself, some received different meanings, in addition, after the Second World War, the writing of many kanji was simplified. Kokuji Kokuji (国字; lit. "national characters") are characters of Japanese origin. Kokuji is sometimes called wasei kanji (和製漢字, lit. "Chinese characters created in Japan"). There are several hundred kokuji in total (see list on Sci.Lang.Japan). Most of them are rarely used, but some have become important additions to the written Japanese language. These include: 峠 toge (mountain pass) 榊 sakaki (sakaki tree from the Camellia genus) 畑 hatake (dry field) 辻 tsuji (crossroads, street) 働 do:, hatara (ku) (work) Most of these kanji have only kun reading, but some were borrowed by China and also acquired on reading[1]. Kokkun In addition to kokuji, there are kanji that have different meanings in Japanese than in Chinese. Such kanji are called kokkun (国訓), including: 沖 oki (seaside; Chun gargling) 椿 tsubaki (Camellia japonica; Chun Ailant) Old and new characters The same kanji can sometimes be written in different ways: 旧字体 (Kyujitai, lit. "old characters") (舊字體 in kyujitai spelling) and 新字体 (Shinjitai; "new characters"). Below are several examples of writing the same character in the form of kyujitai and shinjitai: 國国 kuni, kok(u) (country) 號号 go: (number) 變変 hen, ka(waru) (change) The kyujitai characters were used until the end World War II and are basically the same as traditional Chinese characters. In 1946, the government approved simplified Shinjitai characters in the Toyo Kanji Jitai Hyo (当用漢字字体表) list. Some of the new characters coincided with simplified Chinese characters used in the PRC. As with the simplification process in China, some of the new characters were borrowed from the abbreviated forms 略字, ryakuji) used in handwritten texts, but older forms of some characters (略字, seiji) could also be used in certain contexts. There are also even more simplified versions of writing hieroglyphs, sometimes used in handwritten texts[1], but their use is not encouraged. Theoretically, any Chinese character can be used in Japanese text, but in practice, many Chinese characters are not used in Japanese. Daikanwa Jiten, one of the largest dictionaries of hieroglyphs, contains about 50 thousand entries, although most of the hieroglyphs recorded there have never been found in Japanese texts. Reading Kanji Depending on how kanji entered the Japanese language, characters can be used to write the same or different words or, more often, morphemes. From the reader's point of view, this means that kanji have one or more readings. The choice of reading a hieroglyph depends on the context, the intended meaning, combination with other kanji and even the place in the sentence. Some commonly used kanji have ten or more different readings. Readings are usually divided into onyomi (on reading or just on) and kunyomi (kun reading or just kun). Onyomi (Chinese reading) Onyomi (音読み) is a Sino-Japanese reading; Japanese interpretation of the Chinese character pronunciation. Some kanji have multiple on'yomi because they were borrowed from China several times: at different times and from different areas. Kokuji, or kanji invented in Japan, usually do not have onyomi, but there are exceptions: for example, the character 働 “to work” has both kunyomi (hataraku) and onyomi (do:), and the character 腺 “gland” (breast, thyroid and etc.) there is only onyomi: sen. They are generally divided into four types: Go-on (呉音; lit. sounding from the kingdom of Wu) a reading adopted from the pronunciation of the kingdom of Wu (the area of modern Shanghai) in the 5th and 6th centuries. Kan-on (漢音; lit. Han sound) reading borrowed from the pronunciation during the Tang Dynasty (7th-9th centuries), mainly from the dialect of the capital Chang'an. To:-on (唐音; lit. Tan sound) reading borrowed from pronunciation during the later Song and Ming dynasties. This includes all readings borrowed during the Heian era and the Edo period. Kan'yō-on (慣用音) are erroneous readings of kanji that were later made the norm of the language. The most common form of reading is kan-on. The go-on readings are most common in Buddhist terminology, such as gokuraku 極楽 "heaven". The to-on readings occur in some words, such as isu 椅子 "chair". In Chinese, most characters have a single Chinese syllable. However, there are homographs (多音字), such as 行 (Chinese han, shin: Japanese ko:, gyo:), different readings of which in Chinese corresponded to different meanings, which was also reflected when borrowed by the Japanese language. In addition to difficulties in conveying pitch stress, most Chinese syllables were very difficult to reproduce in Japanese due to the abundance of consonants, especially in Middle Chinese, in which the final consonant was more common than in modern dialects. Therefore, most onyomi consist of two moras: the second of which is either a lengthening of the vowel from the first mora (and in the case of the first, e and u in the case of o, a consequence of the drift of the language centuries after borrowing), or the syllable ku, ki, tsu, ti or syllabary n as an imitation of Middle Chinese final consonants. Apparently, the phenomenon of softening consonants before vowels other than i, as well as the syllabic n, were added to Japanese to better imitate Chinese; they do not occur in words of Japanese origin. Onyomi is most often encountered when reading words composed of several kanji (熟語 dzukugo), many of which were borrowed along with the kanji themselves from Chinese to convey concepts that did not exist in the Japanese language or could not be conveyed by them. This process of borrowing is often compared to the borrowing of English words from Latin and Norman French, since terms borrowed from Chinese tended to be narrower in meaning than their Japanese counterparts, and knowledge of them was considered an attribute of politeness and erudition. The most important exception to this rule is surnames, which most often use the Japanese kun reading. Kun'yomi (Japanese reading) Kun'yomi (訓読み), Japanese, or kun reading, is based on the pronunciation of native Japanese words (大和言葉, yamatokotoba), to which Chinese characters were selected according to their meaning. Some kanji may have several kuns at once, or may not have them at all. For example, the kanji for east (東) has the following reading:. However, in the Japanese language, before the introduction of hieroglyphs, there were two words to designate this side of the world: higashi and azuma - they became the kunami of this hieroglyph. However, the kanji 寸, which denotes the Chinese measure of length (about 4 cm), has no equivalent in Japanese, and therefore has only onyomi: sun. Kun'yomi is determined by the strong syllabic structure of Yamatokotoba: the kun of most nouns and adjectives are 2 or 3 syllables long, while the kun of verbs are shorter: 1 or 2 syllables (not counting the inflections - okurigana, which is written in hiragana, although it is considered part of the reading of verb-formers kanji). In most cases, different kanji were used to write the same Japanese word to reflect shades of meaning. For example, the word naosu written as 治す would mean “to treat a disease,” while the word spelled 直す would mean “to repair” (such as a bicycle). Sometimes the difference in spelling is clear, and sometimes it's quite subtle. In order not to be mistaken in shades of meaning, the word is sometimes written in hiragana. For example, this is often done to write the word moto もと, which corresponds to five different kanji: 元, 基, 本, 下, 素, the difference in use between which is difficult to discern. Other Readings There are many kanji combinations that use both on and kun to pronounce their constituents: such words are called zubako (重箱) or yuto (湯桶). These two terms themselves are autological: the first kanji in the word zubako is read according to onu, and the second - according to kun, and in the word yuto - vice versa. Other examples: 金色 kin'iro - “golden” (on-kun); 空手道 karatedo: - karate (kun-kun-on). Some kanji have little-known readings called nanori, which are usually used when pronouncing personal names. As a rule, nanori are close in sound to kun. Toponyms also sometimes use nanori, or even readings that are not found anywhere else. Gikun (義訓) - readings of kanji combinations that are not directly related to the kuns or ons of individual characters, but related to the meaning of the entire combination. For example, the combination 一寸 can be read as issun (that is, “one sun”), but in fact it is an indivisible combination of tetto (“a little”). Gikun is often found in Japanese surnames. The use of ateji to write borrowed words also resulted in unusual-sounding combinations and new meanings for kanji. For example, the outdated combination 亜細亜 adzia was previously used to write hieroglyphically for a part of the world - Asia. Today katakana is used to write this word, but the kanji 亜 has acquired the meaning "Asia" in such combinations as to:a 東亜 ("East Asia"). From the obsolete hieroglyphic combination 亜米利加 amerika ("America"), a second kanji was taken from which the neologism arose: 米国 beikoku, which can literally be translated as "rice country", although in fact this combination means the United States of America. Choosing Readings Words for similar concepts such as "east" (東), "north" (北) and "northeast" (東北) can have completely different pronunciations: the kun readings of higashi and kita are used for the first two characters, in while "northeast" would be read in onam:to:hoku. Choosing the correct character reading is one of the main difficulties when learning Japanese. Usually, when reading combinations of kanji, their ons are selected (such combinations are called dzukugo 熟語 in Japanese). For example, the combinations 情報 joho: “information”, 学校 gakko: “school” and 新幹線 shinkansen follow exactly this pattern. If the kanji is located separately, surrounded by kana and not adjacent to other characters, then it is usually read according to its kun. This applies to both nouns and inflected verbs and adjectives. For example, 月 tsuki “moon”, 情け nasake “pity”, 赤い akai “red”, 新しい atarasiya “new”, 見る miru “look” - in all these cases kunyomi is used. These two basic template rules have many exceptions. Kun'yomi can also form compounds, although they are less common than combinations with on. Examples include 手紙 tags “letter”, 日傘 higasa “tent” or the well-known combination 神風 kamikaze “divine wind”[2]. Such combinations can also be accompanied by okurigana: for example, 歌い手 utaite - obsolete. “singer” or 折り紙 origami (the art of folding paper figures), although some of these combinations can be written without okurigana (for example, 折紙). On the other hand, some free-standing characters can also be voiced by onami: 愛 ai “love”, 禅 Zen, 点 ten “mark, point”. Most of these kanji simply do not have kun'yomi, which eliminates the possibility of error. The situation with on'yomi is quite complicated, since many kanji have several ons: compare 先生 sensei "teacher" and 一生 issho: "whole life". In Japanese, there are homographs that can be read differently depending on the meaning, like the Russian zamok and zamok. For example, the combination 上手 can be read in three ways: jozu "skillful", uwate "upper part, superiority" or kamite "upper part, upper course". In addition, the combination 上手い is read as umai “skillful”. Some well-known place names, including Tokyo (東京 tokyō) and Japan itself (日本 nihon or sometimes nippon) are read in onam, although most Japanese place names are read in kuna (for example, 大阪 Ošaka, 青森 Aomori, 箱根 Hakone). Surnames and given names are also usually read by kun (for example, 山田 Yamada, 田中 Tanaka, 鈴木 Suzuki), but sometimes proper names are found that mix kunyomi, onyomi and nanori. They can only be read with some experience (for example, 大海 Daikai (on-kun), 夏美 Natsumi (kun-on) or 目 Satsuka (unusual reading)). Phonetic clues To avoid ambiguity, along with kanji in texts, phonetic clues are sometimes given in the form of hiragana, typed in small point “agate” above the characters (the so-called furigana) or in the line behind them (the so-called kumimoji). This is often done in texts for children, for foreigners learning Japanese, and in manga. Furigana is sometimes used in newspapers for rare or unusual readings, and for characters not included in the list of basic kanji (see below). Total Number of Kanji The total number of kanji in existence is difficult to determine. The Daikanwa Jiten dictionary contains about 50 thousand characters, while more complete and modern Chinese dictionaries contain more than 80 thousand characters, many of which are unusual forms. Most of them are not used in either Japan or China. In order to understand most Japanese texts, knowledge of about 3 thousand kanji is enough. Spelling Reforms and Kanji Lists After World War II, beginning in 1946, the Japanese government began developing spelling reforms. Some characters received simplified spellings called 新字体 shinjitai. The number of kanji used was reduced, and lists of hieroglyphs were approved that were to be studied at school. Variant forms and rare kanji have been officially declared undesirable for use. The main goal of the reforms was to unify the school curriculum for the study of hieroglyphs and reduce the number of kanji used in literature and periodicals. These reforms were of a recommendatory nature; many hieroglyphs that were not included in the lists are still known and often used. Kyoiku kanji Kyoiku kanji 教育漢字 ("educational kanji") is a list of 1006 characters that Japanese children learn in elementary school (6 years of schooling). The list was first established in 1946 and contained 881 characters until 1981, when it was expanded to the modern number. The list is divided by year of study, full name: Gakunenbetsu kanji haito:hyo: 学年別漢字配当表. Jōyō Kanji The List 常用漢字 contains 1,945 kanji, including all kyoiku kanji and 939 kanji taught in high school. Kanji not included in this list are usually accompanied by furigana. The Jōyō kanji list was introduced in 1981, replacing the old list of 1,850 kanji called Toōyō kanji 当用漢字 (“general-use kanji”) which was introduced in 1946. kanji The Jinmayō kanji 人名用漢字 list includes 2 928 hieroglyphs, of which 1,945 completely repeat the list of Joyo kanji, and 983 hieroglyphs are used to write names and place names. Unlike Russia, where the number of names given by newborns is relatively small, in Japan, parents often try to give children rare names, including rarely used hieroglyphs. In order to facilitate the work of registration and other services that simply did not have the necessary technical means for recruiting rare signs, in 1981 a list of Jimmeyo Kanji was approved, and names of newborns could only be given from Kanji included in the list, as well as from the hiragana and catacans. This list is regularly updated with new hieroglyphs, and the widespread introduction of computers that support Unicode has led to the fact that the Japanese government is preparing to add from 500 to 1000 new hieroglyphs to this list in the near future. Giji Gijii (外字), the letters “External hieroglyphs” are Kanji that are not represented in existing Japanese codes. This includes variant forms of hieroglyphs, which are needed for reference books and links, as well as non -niroglyphic characters. Giji can be either systemic or user. In both cases, there are problems in data exchange, since the code tables used for Giji vary depending on the computer and the operating system. Nominally, the use of Hiji is prohibited by JIS X 0208-1997 and JIS X 0213-2000, since they occupy coden cells reserved for Giji. Nevertheless, Giji continues to be used, for example, in the I-Mode system, where they are used for fring signs. Unicode allows you to encode Hiji in a private field. Classification of Kanji Confucian thinker Xu Shen (許慎) in his composition Shoveen Zzetsza (說文 說文 解字 解字), approx. 100 years divided Chinese hieroglyphs into six categories (六 書 書 書 書 書 書 ricuso). This traditional classification is still used, but it is difficult to correlate with modern lexicography: the boundaries of the categories are quite blurry and one kanji can belong to several of them at once. The first four categories belong to the structural structure of the hieroglyph, and the other two to its use. SYo: Kay-Moji (象形 文字 文字) hieroglyphs from this category are a schematic sketch of the depicted object. For example, 日 is the sun, and 木 is a tree, etc. Modern forms of hieroglyphs are significantly different from the original drawings, so it is quite difficult to solve their value in appearance. The situation with the printed font signs, which sometimes retain the shape of the original drawing. Hieroglyphs of this kind are called icon (so: cay - 象形, a Japanese word to designate Egyptian hieroglyphs). This kind of hieroglyphs is a little among modern Kanji. Sidzi-Modzi (指事 指事 文字) Sidzi-Moji in Russian are called ideograms, logograms or simply “symbols”. Hieroglyphs from this category are usually easy to draw and reflect abstract concepts (directions, numbers). For example, Kanji 上 denotes “above” or “above”, and 下 “from below” or “under”. Among the modern kanji there are very few such hieroglyphs. Kayi-Modzi (会意 文字) are often called “composite ideograms” or simply “ideograms”. As a rule, they are combinations of pictograms that make up the general value. For example, Kokuji 峠 (that: he, “mountain pass”) consists of signs 山 (mountain), 上 (up) and 下 (down). Another example is Kanji 休 (yas “rest”) consists of a modified hieroglyph 人 (man) and 木 (wood). This category is also few. Caisay-Moji (形声 文字 文字) such hieroglyphs are called “phono-semantic” or “phonetic-ideographic” symbols. This is the largest category among modern hieroglyphs (up to 90 % of their total). Usually they consist of two components, one of which is responsible for the meaning or semantics of the hieroglyph, and the other for pronunciation. The pronunciation belongs to the original Chinese hieroglyphs, but often this trace is also traced in modern Japanese onnaya reading of Kanji. Similarly, with the semantic component, which could change over centuries since their introduction or as a result of borrowing from the Chinese language. As a result, mistakes often occur when instead of a phono-semantic combination in the hieroglyph is trying to make out the constituent ideogram. As an example, you can take Kanji with the key 言 (speak): 語, 記, 訳, 説, etc. All of them are somehow connected with the concepts of “word” or “language”. Similarly, Kanji with the key 雨 (rain): 雲, 電, 雷, 雪, 霜, etc. - all of them reflect weather phenomena. Kanji with the key 寺 (temple) located on the right, (詩, 持, 時, 侍, etc.) usually have it with Xi or Ji. Sometimes about the meaning and/or reading these hieroglyphs can be guessed from their components. However, there are many exceptions. For example, Kanji 需 (“requirement”, “request”) and 霊 (“spirit”, “ghost”) have nothing to do with the weather (at least in their modern use), and at Kanji 待 待 待 待 待 待 待 待 tie. The fact is that the same component can play a semantic role in one combination and phonetic - in another. Tentu: -Moji (転注 文字) This group includes “derivatives” or “mutually explaining” hieroglyphs. This category is the most difficult of all, since it does not have a clear definition. This includes Kanji, whose meaning and application were expanded. For example, Kanji 楽 denotes “music” and “pleasure”: depending on the meaning, the hieroglyph is pronounced differently in Chinese, which is reflected in different it: the “music” and cancer “pleasure”. Kasyaku-Modzi (仮借 文字) This category is called "phonetically borrowed hieroglyphs." For example, the hieroglyph 来 in the ancient Chinese was a icon denoting wheat. His pronunciation was an homophone of the verb “come”, and the hieroglyph began to be used to record this verb, without adding a new meaningful element. Auxiliary signs of the repetition sign (々) in the Japanese text mean a repetition of the previous Kanji. So, unlike the Chinese language, instead of writing two hieroglyphs in a row (e.g. 時時 Tokidoki, “sometimes”; 色色 Iroiro, “different”), the second hieroglyph is replaced by a repetition sign and is also voiced as if if instead of it There was a full -fledged Kanji (時々, 色々). A repetition sign can be used in the names of its own and toponyms, for example, in the Japanese surname Sasaki (佐々木). The repetition sign is a simplified record of Kanji 仝. Another frequently used auxiliary symbol is ヶ (a reduced kae kae signs). It is pronounced as KA when it is used to indicate the quantity (for example, in combination 六 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月 ヶ月, “six months”) or as ha in toponyms, for example, in the name of the Tokyo Kasumigaseki area (霞ヶ関). This symbol is a simplified record of Kanji 箇. Kanji dictionaries to find the desired Kanji in the dictionary, you need to know his key and the number of features.

Chinese hieroglyph can be divided into the simplest components called keys (less often, “radicals”). If there are many keys in the hieroglyph, one basic is taken (it is determined by special rules), and then the desired hieroglyph is searched in the key section by the number of features. For example, Kanji Mother (媽) must be sought in the section with a three -legged key (女) among hieroglyphs consisting of 13 features. Modern Japanese uses 214 classical keys. In electronic dictionaries, a search is possible not only on the main key, but for all possible components of the hieroglyph, the number of features or reading. Tags:

Japan

Cited 1 time

Like share

0

Like

- I liked the post

- Quoted

- 0

Saved

- Add to quote book

- 0

Save to links

Liked

0