At first glance, there really is nothing sophisticated in haiku - neither clever rhyme nor complex rhythm. The translations do not even preserve the well-known 5-7-5 syllable pattern, so it seems that anyone can compose such a tercet.

What is my evidence? Please:

I’m writing an article for the magazine “Knife”... I’m procrastinating.

Why not a new masterpiece? But it's not that simple. The contours of any literature are determined by the language whose means it uses. Therefore, before setting off on a journey where frogs bravely jumping into a pond await us, irises turning into lilies in one movement, and butterflies fluttering in dreams, it is worth saying a few words about the specifics of Japanese phonetics and vocabulary.

Just a little about waifu and syllabic phonography

In the Japanese language there are no consonants that act in our usual role as individual sounds. Instead of [k], a whole string of syllables is used: [ka], [ki], [ku], [ke] and [ko]. All other consonants are also joined by one of the five vowels [a], [i], [u], [e], [o] and in rare cases ['a], ['u], ['o] (soft variety - cf. Russian "mal" [small] - "crumpled" [m'al]). This recording system is called syllabic phonography.

It is precisely because of the syllabic phonetics of the Japanese language that Japanese first and last names always end in a vowel.

This phonetic feature of the Japanese language even affects borrowed words, and, for example, the English “fork” - fork - turns into foku, and wife and husband - into waifu and hazubando, familiar to modern lovers of Japanese culture. So you shouldn’t be surprised when on the English-language Internet, in the dialogue of otaku animation fans, you come across something like this: “A waifu with a naifu will end your laifu.”

Otaku is being threatened! Source

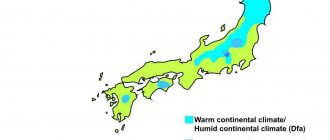

Dreams about scary Russia

Naturally, such phonetic patterns significantly reduce the number of possible phonetic combinations, since clusters of consonants are excluded in this case. Therefore, the Japanese language is extremely homonymous, that is, it is replete with identical-sounding words with different meanings. There are such in Russian: one braid is braided by a ruddy peasant woman, the second is taken off the wall by her husband and goes for hay, and the third is washed in the river from sand. The key can come out of the ground and open the lock.

Most likely, it was the high level of homonymy in the language (already imbuing the text with different meanings) that led to the fact that Japanese poetry does not gravitate towards rhymes: as can be seen in the example of the above meme about an evil waifu with a knife, you can easily collect consonant lines from only borrowed words. However, by actually excluding rhyme as an artistic means from the poetic toolkit, homonymy opens up a huge space for playing with words and meanings, making possible associative chains that cannot be built with the same grace in other languages.

A similar technique can be seen in the funny neologism kotatsumuri, composed of two words: “kotatsu” and katatsumuri - “snail”. In Japan, there is almost no central heating anywhere, so in winter the thermometer in apartments can drop quite low. And to keep warm in the cold, local residents traditionally use kotatsu - small tables covered with a thick blanket, under which there is a heater.

After a hearty lunch, many Japanese people want to crawl deeper under a warm blanket and hide there, just as the aforementioned mollusks hide in their own shell. So it turns out “kotatsumuri” - “snail on kotatsu”.

Snail kotatsu.

Source This example refers to partial homonymy, when the words do not completely coincide: in this case, the sound [a] changes to [o]. However, there is often complete phonetic identity. For example, every resident of the Land of the Rising Sun, who has visited Russia at least once, knows the word osoroshia for sure. The place name in Japanese loses the double [s] and becomes simply Roshia. And then God himself ordered to cross it with the adjective oshoroshii - “terrible”. It turns out to be a funny word that perfectly describes the feelings of foreigners who have seen the Russian winter.

How did haiku come about?

To understand what haiku is and why it’s great, you should look at the history of the genre. The name literally means “initial stanza,” which shows its historical affiliation with renga, an ancient form of versification in Japan. The independent life of the genre of poetry began in the 17th century, when Edo was the capital. In the 19th century, the haiku genre appeared, incorporating some of the poems previously called haiku.

For the Japanese, haiku is not just poetry, but also a reflection of the worldview, the idea of beauty, and the philosophy of life. A small work (only three lines!) is filled with deep meaning.

It is known that haiku has roots in the lower classes: the source of the genre is among the common people. Ancient peasants had fun by composing poems reflecting their life. Initially, the public loved the five-line poems, which consisted of two stanzas: the first with three lines and the second with two. The meaning, the essence of the work was stabbed into the first lines.

This is how the courtiers’ tradition of composing beautiful poetry arose. Each emperor considered it necessary to have a court poet who came from a simple family, who proved his talent through poetry, and not through family and friendly ties.

Tercetics are related to the renga genre

I'll wait for you by the pine tree

From the earliest times, Japanese poets willingly used homonymy in their works, both jokingly and seriously. Thus, matsu can be the verb "to wait" and the noun "pine", and word play based on such phonetic coincidence is often found in classical poetry. When mentioning this tree in their poems, their authors almost always introduced the theme of waiting for a meeting into the work. Here is a short song from the oldest poetic anthology “Man'yoshu” (VII-VIII centuries) translated by Anna Gluskina, which uses this technique:

Without taking your eyes off the green pine

, What grows near my house, I will

wait

for you, Come back to me soon, Oh, before I die of melancholy!

The Japanese poetess used the word matsu once, but in both mentioned meanings at the same time, and the Russian translator needed two lines to convey the meaning contained in it.

In a very similar song from the same collection, a girl is reminded of her lover by a pine tree, which they traditionally planted together:

Oh, if you had not come here, it would still be a green pine

The one who was planted together with you, so that she could serve as a memory for us,

wait for

, my dear.

Peculiarities

The haiku tercet is a lyrical work reflecting human life, natural beauty, and the unity of the seasons. This philosophy, along with the rules for creating a poem, formed the basis of the Code of Poetry. Each work of this form is an example of a stable style and a laconic but capacious image.

It is very difficult to collect all the beauty of the world into 17 syllables, so a successful work leaves a lasting impression. Researchers note: reading haiku, everyone feels capable of creating such beauty.

Each stanza of haiku is a sketch of the surrounding world. It doesn't say anything, it looks simple and concise. The Japanese compare the work of a talented poet with the hospitality of a host, in whose house you feel like your own.

An amazing feature of haiku is forgiveness of banality. Every word in a work of this form is a reflection of everyday life. The Code allows the poet to choose his own symbols to reflect the meaning, to use minimal means to create a complete, deep image. Haiku is not full of meaning, which makes it different from Western works. There is no place for reasoning or redundant symbols. Poetry is characterized by lyrical feeling, but lyrical silence takes on special significance.

Getting rid of the strained search for meaning is the essence of Zen, a religion that has greatly influenced the cultural sphere of Japan. Zen is opposed to unsound, excessive meaning, careless statements. Haiku, following the philosophy of Buddhism, strives for linguistic smoothness and does not allow the overlap of meanings or the layering of symbols.

Japanese poetry reflects the philosophy of Buddhism

How the iris turned into a lily

The most elegant example of the use of homonymy can be found in the collection of short stories “Ise Monogatari”, which has become a standard of refined literature. It consists of short stories, each of which features a tanka. At first glance, these five lines appear as isolated episodes, but upon deeper study it turns out that we are dealing with stories from the life of an unnamed “gentleman” - a court aristocrat and poet. In one of the short stories, the hero, along with several friends, goes on the road and stops in the marshy town of Yatsuhashi in Mikawa Province to eat dried rice.

They dismount and hang their outerwear on the trees. The wind ruffles its floors, bringing melancholy to everyone: the heroes are far from the capital, where the gentleman still has his beloved.

And suddenly travelers notice that Japanese kakitsubata irises are blooming in all their glory in the swamps. Seeing this, the friends invite the main character to write improvised stanzas that should reflect their melancholy. But as an additional condition, they require that it be an acrostic poem - a poem where the first letters or syllables of each line form a certain word. “Kakitsubata” - “iris” was chosen as such.

Ka

ra koromo

Ki

tsutsu nare ni shi

Ts

uma shi areba

Ha

rubaru kinuru

Ta

bi o shi zo omou

According to the rules of the Japanese language, “ha” in the fourth line is voiced (turns into [ba]). Thus, five syllables add up to the required word “kakitsubata”.

Translating these lines into Russian is incredibly difficult. First, you need to save the acrostic. Secondly, homonym words come into play, which actually turn one expression into two due to the fact that the associative chain creates a touching subtext. The word tsuma can mean both "robes" and "wife." The verb nareru (here nare) is usually translated “to get used to” - however, it is used in relation not only to inanimate things, such as clothes, but also to another person, and in the second case we are already talking about a long-term love affair. Harubaru - “to flapping in the wind” and “very far away.”

A literal translation would sound something like this:

I look at the court clothes that I am used to wearing: the wind ruffles their floors. And I think with sadness - We have come far on our journey.

But if we take into account the second meanings of the listed homonyms, a completely different picture is created:

I left far away in the capital my beloved wife in exquisite clothes. And I think with sadness: We have come far on our journey.

In fact, we have before us not one, but two completely different works. In the first, the court clothes fluttering in the wind, hanging on tree branches, evoke melancholy on the poet, because he remembers the splendor of the capital he left, where all the aristocrats wear a similar outfit. In the second, the experiences are much more intimate, personal: the beloved wife of the lyrical hero, dressed in a luxurious dress, remained in that very capital. When translating into Russian, “packing” both meanings into short five lines, and even preserving the acrostic with the word “kakitsubata”, is almost impossible.

Here's how the great Soviet Japanese painter Nikolai Iosifovich Conrad coped with this task:

L

left

my beloved in the clothes

And

the beautiful ones there, in the capital

And

with sadness how

I am

from her...

Obviously, it will not work to put the word “iris” into a five-line tanka in the form of an acrostic, since it only has four letters. Therefore, the translator is forced to replace “iris” with “lily” and focuses on the second, more lyrical semantic layer, where the poet mourns the separation from his beloved woman.

Screen "Irises". Author: Ogata Korin. Source

Family tree of Japanese poetry

The above examples of lyrics refer to waka poetry, which for many centuries was considered the standard of versification. The tradition of haiku (or “hoku”, as it is often called in Russia) arose later and acquired its final features around the 16th century, while the heyday of tanka occurred in the Heian period (7th–12th centuries). However, although these forms are separated by entire eras, they are related by another Japanese poetic genre associated with both of them - renga chains.

The latter are somewhat reminiscent of a freestyle rap battle: one poet composes a tercet or takes well-known literary lines (haiku) in the 5-7-5 syllable format, for which the second must come up with a final couplet (ageku) according to the 7-7 scheme. All together they form the five lines of the tank that are already familiar to us. Then the first participant in the competition adds three of his own to the previous two lines, composing a reverse tanka, after which his colleague ends the work with a new couplet, turning the previous three lines into a new tanka with his stanza.

However, despite the apparent complexity of the rules and the severity of the form, the renga genre arose as literary hooliganism. Here is an example of a very shocking couplet from such a chain, which begins quite innocently and even artistically:

The haze robe was wet at the hem.

The poet is trying to show the image of mountains, the tops of which are far from the viewer, so they look lighter, and the dark foothills are shrouded in fog and resemble the wet hem of a dress. But in the following lines the author explains this metaphor in an original way:

Then spring has come - And now the goddess Sao is urinating while standing.

From such initially crudely humorous tercets, composed according to the 5-7-5 scheme, an entire genre of poetry grew, which in the 20th century would take over the whole world, captivating with its modest beauty and philosophical mood.

Cheat Sheet of Poetic Forms and Japanese Poetry

=========================== CHEET SHEET ====================== ===== In Japanese poetics there is a term “after-feeling”. The deep echo generated by the tanka does not subside immediately. A feeling, compressed like a spring, opens up, an image sketched in two or three strokes appears in its original integrity. The ability to awaken the imagination is one of the main properties of Japanese poetry in small forms. A short poem (just a few words) can become a powerful capacitor of thought and feeling. Each poem is a small poem. She calls you to think, to feel, to open your inner vision and inner hearing. Sensitive readers are co-creators of poetry. Tanka, literally “short song,” originated in the depths of folk melodies in ancient times. It is still recited in a chanting manner, following a certain melody. Thangka is just five verses. The metric system of the tank is extremely simple. Japanese poetry is syllabic. A syllable consists of a vowel sound or a consonant combined with a vowel; There are not very many such combinations. Frequent repetitions create a melodious euphony. Tanka contains many constant poetic epithets and stable metaphors. There is no final rhyme; it is more than replaced by the finest orchestration, a roll call of consonances at the beginning and in the middle of the verses. (from the preface by Vera Markova to the book “Japanese five-line. A drop of dew”) https://www.stihi.ru/diary/svetlanavalent/2015-07-12 Tanka (otherwise waka or uta) is a traditional genre of Japanese poetry, a syllabic five-line in size 5-7-5-7-7 syllables. *(In the competition, deviations from the canon of the form are allowed for a 5-syllable line - 4-6 syllables, for a 7-syllable line - 6-9 syllables. However, the form 5-7-5-7-7 is preferable.)

At my gate There are ripe fruits on the elm trees, Hundreds of birds are nibbling them, having flown in, Thousands of different birds have gathered, - But you, beloved, are not there... Unknown author (translation by A. Gluskina.)

“According to the classical canon, the tanka should consist of two stanzas. The first stanza contains three lines of 5-7-5 syllables, respectively, and the second - two lines of 7-7 syllables. The total is a five-line verse of 31 syllables. This is what form is all about. I draw your attention to the fact that a line and a stanza are different things. The content should be like this. The first stanza presents a natural image, the second - the feeling or sensation that this image evokes. Or vice versa." (Elena One of the most accurate definitions of yugen can be recognized as Tanka Fujiwara Toshinari, who created his teaching about yugen in poetry:

In the twilight of the evening, an autumn whirlwind over the fields pierces the soul... A quail's complaint! Village of Deep Grass.

Yugen is a feeling of the fragility of existing things, but poets loved the state of “wandering in uncertainty” (tadayou). If aware is light yang, then yugen is impenetrable yin...

TANKA 5-7-5-7-7 is a short song * has no rhyme * The first three lines of a tanka are haiku, or haiku * In general, the first three lines should be one sentence. * must consist of TWO stanzas (not formally divided by a space). - The first stanza represents a natural image, - the second - the feeling or sensation that this image evokes. * has styles: aware - light yang, yugen - impenetrable yin, intimate, secret, mystical tadayou - wandering in uncertainty" * ! past tense is not allowed in tanka *! There is a controversial issue regarding pronouns. (FUJIWARA SADAIE also uses them) “...Only I have not changed here, Like this old oak tree” (M. Basho) - Here you have both the pronoun and the past tense

+++ Deep in the mountains, a moaning deer tramples a red maple leaf

I hear him crying... all the autumn sadness is in me

HAIKU-Hoku 5—7—5

* haiku text is divided in a 12:5 ratio - either on the 5th syllable or on the 12th. * the central place is occupied by a natural image, explicitly or implicitly correlated with human life. * the text must indicate the season - for this purpose kigo - “seasonal word” is used as a mandatory element * haiku is written only in the present tense: the author writes down his immediate impressions of what he has just seen or heard. * haiku has no name * does not use rhyme * The art of writing a haiku is the ability to describe a moment in three lines. * every word, every image counts, they acquire special weight and significance * Saying a lot using only a few words is the main principle of haiku. * Haiku poems are often printed on a separate page. This is done so that the reader can thoughtfully, without rushing, penetrate the atmosphere of the poem. ++++ A raven sits alone on a bare branch. Autumn Evening (Matsuo Basho)

RUBAI - quatrains that rhyme like

* aaba, - the first, second and fourth rhyme...... less often - * aaaa, - all four lines rhyme.

++++ Flowers in one hand, a permanent glass in the other, Feast with your beloved, forgetting about the whole universe, Until a tornado of death suddenly tears off the petals from a rose, the shirt of mortal life. (Omar Khayyam)

I went out into the garden in sorrow and was not happy about the morning. The nightingale sang to Rose in a mysterious way: “Show yourself from the bud, rejoice in the morning, How many wonderful flowers this garden has given!” (Omar Khayyam)

SINQWINE 2—4—6—8—2

* used for didactic purposes, as an effective method for developing figurative speech * useful as a tool for synthesizing complex information, as a cross-section for assessing students’ conceptual and vocabulary knowledge. * Sinkwine 1 line - a noun denoting the theme of syncwine 2 line - 2 adjectives, revealing some interesting, characteristic features of the phenomenon of the object stated in the theme of syncwine 3 line - 3 verbs, revealing actions, influences characteristic of this phenomenon, the subject 4 line - phrase , revealing the essence of a phenomenon, an object, reinforcing the previous two lines; line 5 is a noun that acts as a result, conclusion

Reverse syncwine - with the reverse sequence of verses (2-8-6-4-2); Mirror syncwine is a form of two five-line stanzas, where the first is a traditional syncwine, and the second is a reverse syncwine;

Cinquain butterfly - 2-4-6-8-2-8-6-4-2; Crown of cinquains - 5 traditional cinquains forming a complete poem; A garland of cinquains is an analogue of a wreath of sonnets, *a crown of cinquains, to which is added a sixth cinquain, where the first line is taken from the first syncwine, the second line from the second, etc.

Strict adherence to the rules for writing syncwine is not necessary. For example, to improve the text, you can use three or five words in the fourth line, and two words in the fifth line. It is possible to use other parts of speech. Writing a syncwine is a form of free creativity that requires the author to be able to find the most significant elements in information material, draw conclusions and formulate them briefly. In addition to the use of syncwines in literature lessons (for example, to summarize a completed work), it is also practiced to use a syncwine as a final assignment on the material covered in any other discipline.

WEDSING - ultra-short poetic form

*poem of two lines with a total of six syllables. 3+3 or 2+4. * there should be no more than five words * there should be no punctuation marks.

++++ Japanese butterfly (Alexey Vernitsky)

Siberia hyperlink (Roman Savosta)

where we are good there (Oleg Yaroshev)

Continuation

https://www.stihi.ru/2015/07/09/8554 Self-study in writing Japanese poetry, part 1

Senryu (Japanese; “river willow”) is a genre of Japanese poetry that emerged during the Edo period. The form coincides with a haiku, that is, it is a tercet consisting of lines of 5, 7 and 5 syllables in length. But, unlike the lyrical genre of haiku, senryu is a satirical and humorous genre, far from admiring the beauty of nature. It is characteristic that senryu usually do not contain kigo - indications of one of the four seasons, mandatory for classical haiku.

In Japan's laughter culture, humor has always prevailed over satire. T. Grigorieva writes about this in the book “Japanese Artistic Tradition”. Therefore, haiku in the senryu genre were not persecuted by the authorities, as would happen with satirical works. Satire can end up in opposition to power even when it does not touch upon social issues: through the constant denunciation of morals, if the spiritual authorities consider this a violation of the monopoly of the top on criticism. But the senryu did not engage in moral denunciation of ordinary human vices. It is rather, even in satirical poems, a genre of joke, anecdote, sketch.

Although outwardly, in their content, senryu are similar to European jokes, there is a fundamental difference between senryu and the European laughter tradition. Senryu had a serious ideological justification, and senryu masters did not consider themselves poets inferior in aesthetics to the poets of past eras. Laughter in Japanese is "okashi". Here is what T. Grigorieva writes about the laughter culture of 18th-century Japan: “It is not surprising that Hisamatsu puts okashi on a par with aware, yugen, and sabi. They have equal rights. Each time has its own feeling: the severity of Nara, the beauty of Heian, the sadness of Muromachi, the laughter of Edo. Society removed what it was losing interest in and brought to the fore what it needed. The criterion of beauty remained constant.”

Senryu got their name from the poet Karai Senryu (;;;;, 1718-1790), thanks to whom the genre gained popularity.

Useful links https://haiku.ru/frog/def.htm Alexey Andreev WHAT IS HAIKU? https://www.haikupedia.ru/ Haikupedia - encyclopedia of haiku https://tkana.zhuka.ru/kama/ugan/ In the style of yugen https://www.stihi.ru/2015/07/06/4101 meetings at star bridge V. competition poems Haiku competition (judging rules) https://www.stihi.ru/avtor/rengekonkurs Ryoanji Garden Competitions https://www.stihi.ru/2015/07/03/140 goodbye forever... acro- tank... attempt 6 https://termitnik.dp.ua/poem/152528/ TERMITnik of poetry Classics (Acro-tank) Konstantin

https://www.stihi.ru/avtor/wanadis Tania Vanadis https://www.stihi.ru/avtor/cunamisan Tsunami San https://www.stihi.ru/2013/01/07/7485 Dictionary of Russian kigo - seasonal words

1. Haiku or haiku - (initial stanza) unrhymed tercets of 17 syllables (5+7+5). 2. Tanka - (short song) unrhymed five lines of 31 syllables (5+7+5+7+7). The roots of poetry are in the human heart. 3. Kyoka - (crazy poetry), size like a tanka. 4. Rakushu is a satirical type of tank. 5. Teka or Nagauta - (long song), tanka size, up to 100 lines. 6. Busoku-sekitai - (the soul of nature - the soul of man) translated - “Trace of the Buddha” - unrhymed six lines of 38 syllables (5+7+5+7+7+7). 7. Sedoka - (song of the rowers) unrhymed six lines of 38 syllables (5+7+7+5+7+7). 8. Shintaishi - (new verse) - the beginning, like a tanka, the total volume is unlimited - romantic poetry was approved by the poet Shimazaki Toson at the beginning of the twentieth century. 9. Cinquain - unrhymed five-line verse of 22 syllables (2+4+6+8+2) - was invented and put into use at the beginning of the twentieth century by the American poetess A. Crepsi.

SEDOKA - A genre of Japanese poetry - six lines in which the syllables in the lines are arranged as follows: 5-7-7-5-7-7

The eyes are sad, Wrinkles are like paths. Left behind by life... Where is the surgeon, What does plastic surgery of the Body and soul?... KLARA RUBIN, LITO MEMBER, ... We have been coexisting for a very long time. But they didn’t have time to talk. It would be nice in heaven for us to be in the same squadron. ALEXANDER FREIDLES, MEMBER OF LITO, ... It's drizzling rain. My pride is crying, Saying goodbye to you in my thoughts - Captive of feelings. The soul will perk up a little. Wash away the tears from your face. KIRA KRUZIS IS A MEMBER OF LITO.

PS: Do not use the cheat sheet as the basis for everything... it was collected from what was available on the Internet at that time (it was created for me)

© Copyright: My Sun, 2015

https://www.stihi.ru/2015/07/09/5249

And yet, which is correct: haiku or haiku?

Trick question! It depends on which poet we are talking about: some wrote haiku, others wrote haiku, and still others even wrote haikai.

Let's try to figure it out.

As already mentioned, the term “haiku” refers to the tercets in the renga chain. So if we are talking about a poet who participated in a Japanese rap battle, then, of course, he composed them (and perhaps also ageku). However, haiku cannot be considered a separate genre - it was originally a technical name for a specific part of a larger work.

Subsequently, haikai tercets also branched off from renga. In form, they look the same as haiku - 5-7-5 syllables, but have a certain set of characteristics, which will be discussed later. Poets who lived before the 19th century, including the “great trinity” Basho, Buson and Issa, certainly composed haikai.

“Haiku” is a neologism proposed by literary theorist Masaoka Shiki in the 19th century. He advocated the return of the seemingly extinct genres of tanka and haikai to Japanese versification. As the name suggests, Shiki combined the first syllable of haikai with the last syllable of haiku to create a term for new poetry in the old style. So if our contemporary writes Japanese tercets, haiku come from his pen.

But the neologism Shiki took root in literary criticism and replaced the term “haikai”, so even the works of early poets are often called it, although, of course, they themselves did not know about such a genre and could not have known.

Masaoka Shiki. Source

About haiku

Haiku , or haiku, is probably the most popular genre of Japanese poetry throughout the world. This genre originated in the 14th century. But haiku became an independent genre only in the 16th century. In general, haiku originally meant the first stanza of renga, or the first stanza of tanka. The term haiku is an author's one; it was proposed by the Japanese master, poet and critic Masaoka Shiki only in the 19th century. The role of haiku is difficult to overestimate, because haiku was aimed at democratizing Japanese poetry. Haiku at that time was a new trend in poetry, but even then it freed everything from canons and rules. It was a real revolution in the field of posing. The haiku school attracted educated people from among the intelligentsia into its ranks, and there was a kind of “descent” of poetry to the masses.

By the way

Haiku grew from simple peasant entertainment into court poetry. At the court of every Chinese and Japanese emperor there was a poet who composed haiku. Often such poets came from simple families, but their skill in writing haiku was excellent and the emperor bestowed upon them wealth and titles.

The main themes of haiku were court intrigue, nature, love and passion.

Poetic one palm clap

As we see, haiku go back simultaneously to tanka pentaverses with their exquisite play on words, homonymy, sensual admiration of nature, and to humorous renga chains, in which the ability to preserve the theme set by the previous author was valued, while changing it in an unexpected way and creating a new artistic "refraction". But, in addition to the poetry of previous centuries, the formation of the genre was also influenced by religious philosophy, primarily Zen Buddhism. His followers (including those who were endowed with literary gifts) perceived the world in a special way.

Unlike the aristocrats who composed tanka, the haijin - the poet who writes haiku - did not use the surrounding reality as a mirror reflecting the subtle experiences and mental fluctuations of a person.

He lived “in the moment”: for him, a raven perched on a branch is a reason to contemplate the world and seek enlightenment in the ordinary. It is not surprising that many haiku are so similar to Zen koans.

The poem in the epigraph about an old pond into which a frog jumps, making a splash in the silence, subtly recalls the koan about the clap of one palm.

And here are the beautiful lines of Kaga no Chiyojo:

Tell me, butterfly, What did you see in your dream, flapping your wings?

Most likely, the poetess was referring to a well-known parable about the Chinese thinker, popular among Zen circles: “Once Zhuang Tzu dreamed that he was a butterfly, a cheerfully fluttering moth. He enjoyed it wholeheartedly and did not realize that he was Zhuang Tzu. But suddenly he woke up, was very surprised that he was Chuang Tzu, and could not understand: did Chuang Tzu dream that he was a butterfly, or did the butterfly dream that she was Chuang Tzu?!

Song Chuang Tzu. Source

Haijin Poet's Cookbook

The main canons of haiku were formed as a result of the fusion and reinterpretation of the characteristic features of those genres to which this form historically dates back - lyrical and refined tanka, renga with their unexpected outcome and Zen Buddhism, which proclaims a contemplative and philosophical view of the world.

1. The rhythm of 5-7-5 syllables, which is almost never preserved in translation, since Russian words are usually longer than Japanese ones.

2. Kireji - a “cutting word”, emphasizing the rhythm and breaking the text in the proportion of 5/12 or 12/5 syllables - depending on whether it is in the first or second line. For example, a joyful exclamation “I” or a thoughtfully drawn-out “kana” can be used in this capacity.

3. Kigo - “seasonal word”. There are a huge number of them, so special collections are published for haijin.

And the seasons themselves in Japanese culture are not four, like Europeans, but more: their number could reach 72, and each had its own kigo.

Seasonal words are the names of plants and animals that bloom at a certain time, and designations of weather phenomena characteristic of this time. For example, in the spring it would be appropriate to use the image of sakura as a kigo, since it blooms in March-April.

4. Haiku is contemplative creativity “on occasion”, the transmission of momentary thoughts and emotions. Although there were “armchair” poets, it is believed that a good poem should be written at the moment in question.

5. A comparison of images that “overlap” each other, which is why very often unexpected parallels arise between two seemingly completely unrelated phenomena. For example, in Kobayashi Issa’s haiku dedicated to the Buddha statue in the city of Kamakura, the poet speaks of the “eternal” - a huge statue of the deity - and the “transient” - a tiny swallow:

Buddha on high! A swallow flew out of his nostril.

It seems that it is almost impossible to squeeze everything listed into such a compact form. But here is Basho’s poem about a pine tree that is waiting (or not waiting) for winter:

Shigure o ya Modokashi gari te Matsu no yuki

In D. Smirnov’s translation it sounds like this:

Drizzling rain - Sad pine dreaming about snow.

The exclamation ya is used here as a kireji (the translator emphasizes the logical pause with a dash). Drizzle is a seasonal kigo word that refers the reader to late autumn: the imagination immediately draws a bright picture - a pine forest wet from cold rain.

The comparison of precipitation here is a kind of inversion: the poet draws a visible image of damp autumn - and instantly breaks it, making us remember the light snow that settles on the thorny branches.

And thanks to the already familiar homonyms matsu, that same duality arises: the pines are either waiting for it to snow, or are already dusted with it. Therefore, in Vera Markova’s translation, the same verses sound differently:

Bored with the long rain, At night the pines drove him away... Branches in the first snow.

And here is Basho’s “culinary New Year’s” haiku:

Mochiyuki wo Shiraito to nasu Yanagi kana

Kigo mochiyuki is snow falling in large flakes. But the mochi part can also mean mochi, a Japanese rice cake usually prepared for New Year's Day. Shiraito is another name for a traditional winter food: mochi cut or stretched into long, thick noodles. Looking at the snowfall, the poet remembers the New Year's delicacy and thinks that soon the flakes will settle on the willow branches, turning them into snow-white shiraitomoti noodles.

The word “kana” serves as kireji, which is almost always omitted in translation. In this case, it stands at the very end of the verse, giving it internal completeness.

Under the mochi flakes, Willow twigs turned into snow noodles...

Translation by the author of the article

And in conclusion, let’s look at an example of the work of a modern haijin poet - Japanese professor of Russian studies Hidetake Kawaraji - translated by Anna Semida, author of the Haiku Daily project. Haiku is a description of a modern picture of everyday life, but using the same classical techniques. Here we find the kigo “rainy season”, and momentary contemplation of the world, and an unexpected juxtaposition of two completely different elements:

It's the rainy season. And everything around has turned green. On the old stamp - Gagarin.

Perhaps like this.

Source