October 17, 2018Art

Engraving, calligraphy and painting: Arzamas has compiled instructions on how to view Japanese art

Author Anna Egorova

Europeans became acquainted with Japanese art in the second half of the 19th century, after the invasion of the American squadron of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853. It created a sensation at international exhibitions, and everything Japanese immediately came into fashion: kimonos, screens, porcelain, prints. “Japanism” penetrated European painting and decorative arts, influencing the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Art Nouveau masters. And yet, for most, Japanese art remained a curiosity: paintings seemed like unfinished sketches, scrolls resembled wallpaper, and engravings resembled caricatures. And even today, many aspects of Japanese art are not entirely clear to Western audiences. How should we understand it?

Periodization of Japanese art

Like nowhere else in the world, in Japan the history of art is closely connected with history, more precisely, with the history of the ruling dynasties. The main periods of development of Japanese painting:

- Yamato (VI – VII century);

- Nara (mid 7th – 8th century);

- Heian (late 8th – 12th centuries);

- Kamakura (late 12th – first half of the 14th century);

- Muromachi (first half of the 14th – first half of the 16th century);

- Azuchi-Momoyama (second half of the 16th century);

- Edo (XVII – XIX centuries);

- Meiji (late 19th – early 20th century);

- modern Japanese painting.

Each of the periods differs in the way of artistic expression of the world, the manner of painting, but the predominance of landscapes remains unchanged: this is a cross-cutting motif of Japanese art. Every artist in this country, from ancient to modern, is filled with deep reverence for nature as an eternal source of life.

The most interesting artistic periods are the Yamato, Muromachi and Momoyama periods.

Architectural direction

Initially, Japanese architecture was limited to the construction of ancient traditional houses - haniwa. They were created before the 4th century, and their appearance can only be judged from surviving miniature clay models and drawings, since they have not survived to this day.

The life and everyday life of ordinary people took place here. These were a kind of dugouts, covered with a straw canopy on top. It was supported by special wooden frames.

Later, takayuka appeared - an analogue of granaries. They also consisted of special support beams, which made it possible to save the crop from natural disasters and pests.

Around the same time, in the 1st-3rd centuries, temples of the ancient Shinto religion began to appear in honor of the deities who patronized the forces of nature. They were most often built from untreated and unpainted cypress and had a laconic rectangular shape.

Ise Shrine

The thatched or pine roof was gable, and the structures themselves were built on pillars surrounded by pavilions. Another characteristic feature of Shinto shrines is the U-shaped gate at the entrance.

In Shinto, there is a law of renewal: every twenty years the temple was destroyed, and almost exactly the same, but new, was built in the same place.

The most famous such temple is called Ise. It was first built at the beginning of the 1st millennium and, according to tradition, was constantly rebuilt. Ise consists of two similar complexes located slightly apart from each other: the first is dedicated to the forces of the sun, the second to the deity of fertility.

From the 6th century, Buddhist teachings that came from China and Korea began to spread in the Land of the Rising Sun, and with it the principles of building Buddhist temples. At first they presented Chinese copies, but later a special, truly Japanese style began to be traced in temple architecture.

The structures were built asymmetrically, as if merging with nature. Laconicism and clarity of forms, a wooden frame coupled with a stone foundation, pagodas in several tiers, not too bright colors - this is what distinguishes the sanctuaries of that time.

Many of them have survived to this day. Architectural monuments include Horyu-ji of the early 7th century with its famous Golden Temple and 40 other buildings, Todai-ji of the mid-8th century in the city of Nara, which is still considered the largest wooden structure on the planet. At the same time, Buddhist architecture is closely intertwined with sculpture and painting, which depict deities and motifs from the life of the Teacher.

Todai-ji Temple

At the turn of the 12th-13th centuries, feudalism began in the state and therefore the Shinden style, distinguished by its pomp, became popular. It was replaced by the sein style, which is dominated by simplicity and some intimacy: instead of walls there are almost weightless screens, on the floor there are mats and tatami.

At the same time, palaces and temples of local feudal lords began to appear. The masterpieces of this type of structure are the famous Kinkaku-ji of the 14th century, or the Golden Pavilion, as well as Ginkaku-ji of the 15th century, also known as the Silver Temple.

Ginkaku-ji Temple (Golden Pavilion)

Along with palaces and temples, landscape gardening art began to emerge in the 14th-15th centuries. Its appearance is largely due to the penetration of the contemplative teaching of Zen into Japan. Gardens began to appear around temples and large dwellings, where the main components were not only plants and flowers, but also stones, water, as well as sand and pebble mounds, symbolizing the water element.

The unique Rean-ji rock garden in Kyoto is known throughout the world.

Another type of garden is a tea garden, which is called “tyaniva”. It surrounds the tea house, where a special, leisurely ceremony is held, and a special path runs through the entire garden to the house. Having appeared in the Middle Ages, tyaniva is found everywhere today.

Sumi-e

This technique of drawing with ink on rice paper , brought in the 13th century by Chinese monks, is also called suiboku, suibokuga. Japanese artists have brought it to perfection : monochrome landscapes seem to be painted in watercolors. Typical sumi-e subjects are mountains and ponds.

The brightest representatives of the direction:

- Josetsu . A monk considered the founder of sumi-e. The most famous work is “Catching Fish with a Pumpkin”.

- Toyo Sesshu . His works are the standard of this technique, a striking example of which is “Landscape in the Haboku Style.”

- Sasson . He is interesting not only for his creativity, but also for his origin: he was a samurai. His landscapes often feature animals, as in the painting “Monkeys on Rocks and Trees.”

- Hosegawa Tohaku . Thanks to him, the sumi-e style gained extraordinary popularity. One of the peaks of his work is “Pines”.

Transitions and color solutions

When painting Japanese paintings, transitions are often used. They can be different: for example, from one color to another. On the petals of water lilies and peonies you can notice a transition from a light shade to a rich, bright color.

Transitions are also used in the image of the water surface and sky. The smooth transition from sunset to dark, deepening twilight looks very beautiful. When drawing clouds, transitions from different shades and reflexes are also used.

Ukiyo-e

This is the name given to woodblock prints that are characteristic of Japanese urban art. Their content echoed the themes of urban literature. The artists' focus is on people : geishas, kabuki performers, sumo wrestlers. Landscapes in ukiyo-e appeared much later. This type of woodcut reached its peak in the 17th century, and in the 18th century the technique of color printing .

Other types

Japanese art is multifaceted, and one can talk about it for hours. Let's talk about several more types of art that originated in ancient times.

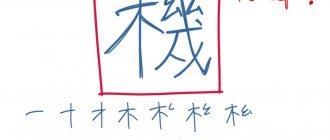

- Calligraphy

It is called sedo, which means “road of notifications.” Calligraphy in Japan appeared thanks to the beautiful hieroglyphs that were borrowed from the Chinese. In many modern schools it is considered a compulsory subject.

- Haiku or haiku

Haiku is a special Japanese lyric poetry that appeared in the 14th century. The poet is called “haijin”.

- Origami

This name translates to “paper that has been folded.” Coming from the Middle Kingdom, origami was initially used in rituals and was an activity for the nobility, but has recently spread throughout the world.

The Ancient Art of Origami in Japan

- Ikebana

The word translated means “live flowers”. Like origami, ikebana was originally used in rituals.

- Miniatures

The two most common types of miniatures are bonsai and netsuke. Bonsai are copies of real trees in a greatly reduced form. Netsuke are small figurines like talisman keychains that appeared in the 18th-19th centuries.

- Martial arts

They are primarily associated with samurai - a kind of chivalry, ninja - mercenary killers, bushido - warriors.

- Theater arts

The most famous theater, the pride of all Japanese, is the classic Kabuki theater. You can read more about theatrical art in Japan here.

Kabuki theater in Japan

Kano Art School

Her influence goes far beyond Muromachi: for 300 years , the Kano family reigned almost unchallenged in Japanese painting. This was greatly facilitated by the support of the shogunate, whose official artists were representatives of the school, starting with the founder, Kano Masanobu (1434–1530). He developed his own original style, taking suibokuga as a basis and adding light illumination with mineral paints.

The creator of Kano’s signature style was Masanobu’s son, Motonobu (1476–1559). He combined writing with ink and the use of paints, but most importantly, the national tradition of Yamato-e was developed in his work. Motonobu also turned out to be a successful entrepreneur: he opened a network of art studios, which grew year by year.

Monotobu's grandson, Eitoku (1543–1590), can perhaps be considered the best master of the Kano school. Screens - an integral element of Japanese interiors - in his design became a symbol of Momoyama's exquisite luxury and a picturesque standard for years to come. The complex landscape, carefully painted on a golden background, is full of many subtle details that elude a quick glance, but bewitching upon closer examination.

The last outstanding representative of Kano was Sansetsu (1589–1651), who worked already in the Edo period, when strict simplicity became fashionable. And although he still worked with gold paintings, it was his ink paintings that brought him fame.

The Kano school is an integral phenomenon , despite the huge number of artists belonging to it. The subject matter of the paintings covers all traditional motifs - landscapes, animals, everyday scenes. The monochrome paintings on silk made by Kano masters are excellent, which are characterized by a combination of a realistic foreground and an abstract background: it depicts clouds, waves, and fog.

In the 19th century, when Japan was no longer introverted and hidden from the world, it was for some time under strong European influence . In art, this was manifested by the competition between traditional and Western styles. But this struggle died out quite quickly, and classical Japanese painting again took a central place in the country's culture.

About personal experience

— Tell us a little about your students.

We started classes in 2014, and a whole army of students has already grown. Many now teach themselves. As the Japanese say, everyone should find their “gigai”, that is, a calling, something that makes a person wake up joyfully in the morning and look forward to doing what he loves, something that nourishes and fills him with strength. It's great that people have found something they love. Especially for women, it is very important to be creative. A woman is the center of the family; the atmosphere at home depends on her. If it is harmonious, then through it love spreads to all family members.

As the Japanese say, everyone should find their “gigai,” that is, a calling, something that makes a person wake up joyfully in the morning and look forward to doing what he loves, something that nourishes and fills him with strength.

— How do you plan your time?

Of course, there is little free time. I am writing plans for the week ahead. At the same time, I have a flexible schedule. I wouldn't be able to go to work every day from bell to bell. I like to be on the move. I plan my time myself. To prepare for my classes, I draw teaching materials. I work a lot, in addition to teaching sumi-e, I do children's watercolor illustrations. As a result, I have one day off, during which I put the house in order. And, naturally, I find time to devote it to myself, my family, and my child. My daughter sometimes gets offended by me, saying, Mom, you’re all busy at work, come and I’ll hug you! She is tall and we have now switched places. I’m sitting on her lap, it’s so funny: “Mom, come to me, sit on my lap”:)

— Tell us about your plans and inspiration.

The plans are very big: I want to make a book of step-by-step drawing of sumi-e. I know this is very relevant and will be in demand by students. There are separate selective lessons, they can be found on the Internet. However, a full-fledged textbook has not yet been published.

Literally everything inspires! Nature, books, children's drawings... The child made a blot, got upset, and I said: “Look, it’s not a blot, it’s a bird!” – a couple of strokes – and already a smile on the child’s face! This is how you teach them to see an object in every blot and understand that everything can always be corrected. Art is designed to bring light into the depths of the human heart. When a person begins to engage in art, he does not feel the meaninglessness of his existence, his life is filled with joy and light. This is great! Man creates another reality with art. And he can create it the way he wants.

— What is your life philosophy?

Love, creativity, children - these are the three pillars on which everything rests. I love children, I love to create, I am a person who is in feelings. Love is important to me because nothing nourishes a creative person like love. People won't remember what you said to them, but they will always remember how they felt when you were around them.

The attitude towards people is very important to me. I want you to feel good and comfortable next to me. After all, we leave a trail, a halo of communication, and I want my students to leave my classes with an atmosphere of warmth and comfort.

People won't remember what you said to them, but they will always remember how they felt when you were around them.