Etiquette must be observed even in friendship. Japanese proverb

Japan is a country of high technology, sushi, sakura and Mount Fuji. Its culture is complex and mysterious. Foreigners do not understand why the Japanese allow themselves to smack their lips loudly at the table, do not open the door for women and do not let them forward.

From this article you will learn a lot about Japanese etiquette: how to greet your interlocutor, how to handle chopsticks, how to behave on public transport, etc.

Japanese etiquette is a complex “science”.

Its origins lie in Confucianism, Shintoism, and the strict hierarchical system of Japanese society.

The Japanese are almost always polite and calm. They understand that it is difficult for a European to adapt to their culture, and they treat mistakes in the behavior of tourists with kind irony. That is why a foreigner’s knowledge of Japanese traditions evokes genuine respect from them.

Magic words

Addressing your interlocutor

Nihongo no keisho are noun suffixes used in communication and added to a person's first name, last name, or profession. They indicate the degree of closeness of the interlocutors and the social connections between them. Addressing without a suffix is rude. It is permissible only in communication between schoolchildren, students and close friends, as well as when an adult addresses a child.

Basic nihongo no keisho:

- -san - used in communication between people of equal social status, younger to older, as well as unfamiliar people, to show discreet respect (something like our “You”);

- -kun – used in informal communication between colleagues, friends, as well as to address a senior to a junior (a boss to a subordinate);

- -chan - used in close communication between people of equal social status and age, as well as as an address to children (something like diminutive forms in Russian);

- -sama – used to express extreme respect, usually in official letters (something like “sir”);

- -senpai - used when a younger person addresses an older person (teacher - student, less experienced employee - more experienced);

- -kohai – reverse “-senpai”;

- -sensei – used when addressing scientists, doctors, writers, politicians and other persons respected in society.

Hello!

Greetings are an important part of Japanese culture. Most often it is expressed by bowing (more on this a little later), but the following words are also used:

- Ohayo gozaimasu - good morning.

- Konnichiwa - good afternoon.

- Kombanwa - good evening.

- Hisashiburi desu - long time no see.

Such informal variants as “Ossu”, “Yahho!”, “Ooi!” are also used. (in a male company).

Goodbye!

To say goodbye, in Japan they say:

- Sayonara - goodbye.

- Matane - bye, see you.

- Oyasumi nasai or simply oyasumi - good night.

Thank you

People in Japan say thank you like this:

- Domo - thank you.

- Domo arigato – thank you very much.

- Domo arigato gozaimas – thank you very much.

Please

And they respond to kindness like this:

- Doitashimasite – no need for gratitude.

- Kotirakoso - thank you.

- Otsukare sama – great job.

Requests

To ask for help, you need to say “onegai” or “kudasai”. But in Japan it is not customary to ask (only in the most extreme cases). Therefore, refusing help is not rudeness, but, on the contrary, a sign of respect. You can only accept someone’s support when the person expresses their willingness to help several times in a row.

Apologies

Common words of apology are “Gomen nasai” and “Sumimasen”. The latter is translated literally as “there is no forgiveness for me” and is used very often. This is how the Japanese show how much they respect their interlocutor who has been inconvenienced in some way.

Bows:They are universal gestures of etiquette; they accompany greetings, congratulations, requests, etc. and may vary depending on the situation. Bows can be performed in three positions: standing, sitting, Japanese, and European. Also, most bows have a female and a male form. When meeting, those lower in age and position bow first and with a more polite bow. According to the degree of politeness, bows can be divided into three groups: 1. standard polite bow (rei, ojigi) with a body tilt of about 30°; 2. everyday standard or lightweight (esyaku) with an inclination of up to 15°; 3. ceremonial or respectful (saikeirei) with an inclination from 45° to 90°.

Types of bows:

—Standing. Bows of this kind are most common in everyday and business communication. The bow itself is performed from the following starting position: those bowing stand opposite each other at a distance of three steps and look into each other’s eyes. While bowing, your back must be kept straight and your legs must be together. Men's hands lie freely at the seams, socks are slightly apart. Women fold their arms in front of them, and their socks may point slightly inward. Those bowing spend about two seconds in a bowed state, after which they slowly straighten up and look at each other again. The most typical situation with a bow is a greeting.

- sitting in Japanese.

Such bows are performed exclusively in rooms with Japanese interiors and are performed from an official sitting position (seiza, hiza o soro-ete suwaru): sitting, resting on your heels and knees, keeping your back straight. Men's hands rest loosely on their hips, women fold them in front of them, and their hips are closed.

- sitting in a European style. Typically performed in European room settings and in formal situations. In personal communication, they are permissible only in relation to a junior or subordinate person. They are performed in the same way as bows while standing, hands are held as when bowing while sitting in Japanese.

Urgent Requests:

Usually accompanied by ceremonial bows with the words: “Kono to: ri onegai shimasu” (“I beg you very much!”).

Requests:

The hands are folded in front of the face and the person asking bends in a slight bow. As a rule, they are accompanied by the words: “Kono to: ri desu” (polite form), “Issho: no onegai” (children’s or youth version), “Kono to: ri” (male version).

Light gratitude (or apology):

This everyday gesture is performed with the help of a light bow, silently or with the words: “Do: mo” or “Sumimasen”, i.e. (“Thank you” and “Sorry”) respectively.

Polite thanks (or apology):

Both are expressed through standard or everyday bows with the words “Do: mo sumimasen” (“Excuse me, please”) or “Arigato: gozaimasu” (“Thank you...”).

Deep gratitude (or apology):

Expressed by standard or ceremonial bows with the words: “Mo: shivake arimasen” (“Very guilty”) or “Orei no kotoba mo gozaimasen” (“There are no words to express my gratitude”). The deepest gratitude or apology can be expressed by ceremoniously bowing while sitting in Japanese: “Te o tsuite ayamaru” (literally: “asking for forgiveness by touching the ground with hands”).

PS I was shocked when a Japanese woman demonstrated types of bows on TV today. Ooh! This is beyond the capabilities of a European... The presenter was only able to bend over 5 degrees. And she was like a taut string!

Ooh! This is beyond the capabilities of a European... The presenter was only able to bend over 5 degrees. And she was like a taut string!

Source: www.thegazette-forum.com

Language of the body

Words are secondary to the Japanese. They express a lot (if not all) in sign language.

The main rule in communicating with the Japanese is that personal space must not be violated.

When talking to someone you don't know, keep your distance. No familiar pats on the shoulder or hugs, no intrusion into your personal comfort zone.

Sight

“The eyes are the mirror of the soul,” we believe. The Japanese are not used to showing off their soul; they almost never look their interlocutor in the eyes.

This has been the case since ancient times: you couldn’t look into the eyes of people higher than you on the social ladder. This was considered unheard of rudeness.

Today, a direct, open gaze in Japan is a sign of aggression, a kind of challenge. For example, when parents scold their teenage children, they do not contradict them, but simply brazenly look into their eyes.

If a Japanese person constantly looks away during a conversation, you should not think that he is being cunning or hiding something. This is fine. It takes some getting used to.

Bow

Greeting, gratitude, apology, respect - the Japanese express all this through bows. Bowing (ojigi) is an integral part of Japanese culture. Some bow even when talking on the phone (automatically, unconsciously). Proper bowing is a sign of good manners.

There are three types of bows:

- Eshaku - a short, barely noticeable bow, the back bend is only 15º. Widely used in everyday life, to greet friends, as well as unfamiliar people of higher status or as a “thank you”.

- Keirei is a deeper (30º) and slightly longer bow. This is how they greet respected colleagues and business partners.

- Sai-Keirei is the strongest (45º) and longest bow, expresses deep respect for a person, it is used to greet very important people.

Types of bows in Japan

To bow correctly, you need to:

- Stay.

- Stand opposite your interlocutor.

- Press your hands to your hips or fold them in front of you (gassho).

- Make a bow.

Note that the Japanese are very progressive. When communicating with foreigners, they increasingly use handshakes familiar to Europeans (especially in business).

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Bows:

They are universal gestures of etiquette; they accompany greetings, congratulations, requests, etc. and may vary depending on the situation. Bows can be performed in three positions: standing, sitting, Japanese, and European. Also, most bows have a female and a male form. When meeting, those lower in age and position bow first and with a more polite bow.

According to the degree of politeness, bows can be divided into three groups:

1. standard polite bow (rei, ojigi) with a body tilt of about 30°; 2. everyday standard or lightweight (esyaku) with an inclination of up to 15°; 3. ceremonial or respectful (saikeirei) with an inclination from 45° to 90°.

Types of bows:

—Standing.

Bows of this kind are most common in everyday and business communication. The bow itself is performed from the following starting position: those bowing stand opposite each other at a distance of three steps and look into each other’s eyes. While bowing, your back must be kept straight and your legs must be together. Men's hands lie freely at the seams, socks are slightly apart. Women fold their arms in front of them, and their socks may point slightly inward. Those bowing spend about two seconds in a bowed state, after which they slowly straighten up and look at each other again. The most typical situation with a bow is a greeting.

- sitting in Japanese.

Such bows are performed exclusively in rooms with Japanese interiors and are performed from an official sitting position (seiza, hiza o soro-ete suwaru): sitting, resting on your heels and knees, keeping your back straight. Men's hands rest loosely on their hips, women fold them in front of them, and their hips are closed. - sitting in a European style.

Typically performed in European room settings and in formal situations. In personal communication, they are permissible only in relation to a junior or subordinate person. They are performed in the same way as bows while standing, hands are held as when bowing while sitting in Japanese.

bows from right to left

Urgent Requests:

Usually accompanied by ceremonial bows with the words: “Kono to: ri onegai shimasu” (“I beg you very much!”).

Requests:

The hands are folded in front of the face and the person asking bends in a slight bow. As a rule, they are accompanied by the words: “Kono to: ri desu” (polite form), “Issho: no onegai” (children’s or youth version), “Kono to: ri” (male version).

Light gratitude (or apology):

This everyday gesture is performed with the help of a light bow, silently or with the words: “Do: mo” or “Sumimasen”, i.e. (“Thank you” and “Sorry”) respectively.

Polite thanks (or apology):

Both are expressed through standard or everyday bows with the words “Do: mo sumimasen” (“Excuse me, please”) or “Arigato: gozaimasu” (“Thank you...”).

Deep gratitude (or apology):

Expressed by standard or ceremonial bows with the words: “Mo: shivake arimasen” (“Very guilty”) or “Orei no kotoba mo gozaimasen” (“There are no words to express my gratitude”). The deepest gratitude or apology can be expressed by ceremoniously bowing while sitting in Japanese: “Te o tsuite ayamaru” (literally: “asking for forgiveness by touching the ground with hands”). PS I was shocked when a Japanese woman demonstrated types of bows on TV today. Ooh!

This is beyond the capabilities of a European... The presenter was only able to bend over 5 degrees. And she was like a taut string!

The presenter was only able to bend over 5 degrees. And she was like a taut string!

Source: www.thegazette-forum.com

Away

The Japanese rarely invite guests (especially foreigners) into their home. And it's not a matter of inhospitality. Just your own house, not a rented one, is a rarity, and its area leaves much to be desired.

If you receive an invitation to come visit, you are greatly honored. It is extremely impolite to refuse.

Present

You cannot go on a visit empty-handed.

Gifts are an important part of Japanese culture.

They are given for holidays, special occasions, as a sign of respect, etc.

At the same time, symbolism and ceremony are very important. There is even a special term “Zoto” - the art of giving gifts.

Basic rules for giving gifts:

- The gift must be wrapped.

- A gift (like any other thing solemnly passed from person to person) should be given and received with both hands.

- You should not immediately unpack a gift (a sign of curiosity and greed).

- The gift should be practical and appropriate for the occasion (money is often given).

- The gift should not include the number 4 (a homophone of the hieroglyph for death).

- You should “apologize” for a gift (even if it is very expensive) (your modest gift still cannot express the respect that you have for the recipient).

- It is customary to write letters of gratitude in response to a gift received by mail.

sunabesyou/Shutterstock.com

So, according to the rules of Japanese guest etiquette, upon entering the house, the guest must stop in the hall (“chenkan”), where the hosts will meet him. The guest must present the gift to the hostess and apologize for disturbing them with his visit. The hosts, in turn, apologize for receiving the guest so modestly.

After such an exchange of pleasantries, you can enter the house.

Shoes

Here a catch awaits the foreigner. In America and Europe, it is not customary to take off your shoes when entering a living space. This is mandatory in Japan.

Entering a house with shoes on is a gross violation of Japanese etiquette. The Japanese forgive many mistakes made by inexperienced foreigners, but not this one. In the Land of the Rising Sun, in some provincial cities, shoes are taken off even when coming to work.

Therefore, before you cross the threshold of a Japanese house, you need to take off your shoes.

Sometimes you will be offered slippers, sometimes not. Here the second catch awaits the guest - always make sure that your socks are clean and intact.

The third catch was lurking near the restroom. Near the entrance to the bathroom or toilet in a Japanese house there are another, special slippers (most likely even flip-flops, with special inscriptions). “And let them stand,” the foreigner will think and cross the threshold in slippers or barefoot, thereby risking exposing himself to ridicule. To use the restroom, you must change your shoes.

In Japan they use special “toilet” slippers

Communication and etiquette in Japan: bows

article translated from tofugu.com

Everything you ever wanted to know about when and how to bow and when not to.

It seems that many people, whether they are preparing for an upcoming short trip to Japan or live there full-time, often have difficulty figuring out how to properly bow as part of Japanese etiquette. Of course, they have a vague understanding of when to bow, but they are afraid of offending their colleagues or friends by accidentally being polite without knowing the subtle nuances.

Bowing is so rooted in Japanese culture and is an integral part of it that the Japanese themselves, doing it intuitively, do not think about certain algorithms and situational conditions. And, in fact, there are a lot of rules! Thus, when in Japan, most foreigners are likely to be puzzled by the question of whether or not bowing is necessary in any given everyday situation. The Japanese understand this and forgive us our ignorance.

But, to be fair, it should be noted that a timely and correctly executed bow will certainly help you win the favor of the Japanese, and this time we have prepared a bowing etiquette guide for you! Here we will introduce you to the basic types of bows you need to know and explain step by step how to perform them.

Why do you need a bow at all?

It is believed that bowing began to spread during the Asuka and Nara periods (538-794 AD) with the arrival of Buddhism from China to Japan. According to this version, bowing was used to differentiate the social status of interlocutors - if you met a person of higher social rank, you should put yourself in a “vulnerable” position. This is similar to how smaller dogs fall on their backs and expose their bellies at the sight of larger ones, and thereby express their submission to show that they are not aggressive towards their opponent and are not going to fight, accepting their loss in advance.

In modern Japanese society, bowing serves many functions far beyond its original purpose. Most often you will bow in the following cases:

- Saying hello and saying goodbye

- Starting and ending a lesson, meeting or ceremony

- In gratitude

- Apologizing

- Congratulating someone

- Making a request

- While performing rituals at the sanctuary

Rather than simply learning these social situations, it is more important to remember that bowing serves to express different emotions, such as gratitude, respect, or remorse. When you learn the technique of bowing, you should also remember that by bowing you are conveying a certain message with your body, and this will determine how deeply and for how long you bow to the interlocutor.

Standing bows or sitting bows?

Before we start talking about the different types of bows you can perform, let's briefly touch on the two starting positions from which you will bow.

The first position is the sitting position, which is called seiza (正座 seiza). Seiza is the position in which to sit in all formal situations, from participating in a tea ceremony to a funeral. To enter seiza from a standing position, you need to start from the knee. A man should rest on one knee first, while a woman should place both knees on the floor at the same time, if possible. When the back of your foot is flat on the floor and your toes are behind you, lower your body onto your shins and heels. Keep your arms by your sides as you sit down, and then place your palms on the top of your thighs. Try to sit as straight as possible. If you have never sat in seiza for an extended period of time before, we recommend that you practice at home, as it will take time until you get used to it and the position becomes comfortable for you.

There is also a standing bow called 正立(seiritsu). To enter seiritsu, stand and look straight ahead at a distance of approximately 5 m 40 cm. If you are a man, place your feet approximately 3 cm apart from each other; if you are a woman, place your feet together. Place your palms loosely on your thighs diagonally, checking that you can stick your fist from your elbow to your body. Finally, breathe from your diaphragm to appear more focused.

Proper bowing etiquette in Japan: the basics

Now that we have looked at the two starting positions of seiza and seiritsu, let's look at three rules that must be followed.

First : Remember that your back, neck and back of your head should form one straight line. An easy way to make sure your back is straight is to have the collar of your shirt touching the back of your head.

Second: When you bow from the seiritsu position, make sure that your feet remain in the same position throughout the bow. In other words, don't push your pelvis back. To understand what the position of your legs should be, imagine that you are standing with your back and legs pressed against the wall as you bow.

Third: Begin the bow as you inhale, hold down as you exhale, and return to your starting position again as you inhale.

We bet you didn't realize there were so many rules for such a simple gesture, did you?

But we hope this part doesn't scare you away. Now we will look at several of the most commonly used variations of bows.

Nod and bow with gaze instead of traditional bow

All rules have exceptions. When you communicate with people you know well, friends or relatives, there is no need to bow. Instead, simply tilt your head slightly.

In very democratic situations, you can even get by with a “respectful look” by bowing only mentally. This form of politeness is called mokurei (目礼 mokurei), a word that includes the characters 目 (eye) and 礼 (bow).

*This word also has the homophone MOKUREI 黙礼 (mokurei) which can be translated as “silent bow”. Don't confuse them.

Esjaku: 15° bow “greeting”

Video

When you meet someone who is your equal in position or social status, such as a colleague or a friend of a friend, you will use eshyaku (会釈).

standing

- Get into seiritsu.

- Lean forward 15° at a natural pace.

- At the same time and at the same speed, lower your hands 3-4 cm along the front of your legs.

- As you bend over, move your gaze, looking straight ahead at a distance of approximately 180 cm.

- Return to seiritsu at a natural pace.

Sitting

- Sit in seiza position.

- Lean forward 15° at a natural pace.

- At the same time and at the same speed, move your hands down to your knees.

- Place your fingertips (lightly touching) on the floor, in line with your body, so that they extend slightly forward.

- Keep your gaze at a natural level.

- Return to the seiza position at the same pace.

- As you can see, you don't need to deliberately linger in any part of the bow, just take your time and move naturally.

Senrei: 30° bow “courtesy”

Video:

When you are in a semi-formal setting and want to express mild gratitude or a sign of respect, you will use senrei 浅礼 (senrei), the most common type of bow in everyday life.

Note: This bow is performed only in a sitting position.

- Sit in seiza.

- Lean forward 30°.

- At the same time and at the same pace, move your hands lower to your knees.

- Men place their palms on the floor, at a distance of 3 cm from the body. Women touch their fingertips to the floor just in front of their knees, with their thumbs touching each other.

- Direct your gaze to the floor opposite you at twice the distance of your height in a sitting position.

- Stay in this position for one second.

- Return to the seiza position at the same pace as you bowed.

Take the time to practice this bow, it should look natural and precise.

Futsurei and Keirei: bow of “respect” from 30° to 45°

Video

If you interact with someone who is socially superior to you, older, or has some kind of dominance over you, such as your boss or in-laws, you will perform futsurei 普通礼 (futsu:rei) or keirei 敬礼 (keirei). Futsu 普通 futsu:) translates to "common" and the character kei 敬 (kei) means "respect", so take these bows as expressions of respect in all appropriate situations.

standing

- Get into seiritsu position.

- Bend forward 45°, taking one full breath.

- At the same time and at the same speed, move your hands down the front of your thighs.

- Leave your hands 7-10 cm above your knees.

- Return to seiritsu while exhaling slowly.

Sitting

- Sit in seiza.

- Lean forward for 2.5 seconds until your head is 30 cm from the floor.

- Then place your hands on the floor so that your thumbs and index fingers form a triangle.

- Keep your forearms close to your body and your elbows slightly off the floor.

- Direct your gaze in the direction of your index fingers, bending your face parallel to the floor.

- Hold this position for 3 seconds.

- Slowly straighten your body for 4 seconds and return to the starting seiza position.

Saikeirei: "reverent" or "respectful" bow from 45° to 70°

Tourists and foreign nationals living in Japan rarely have the opportunity to make a saikeirei 最敬礼 (saikeirei), as this bow expresses the deepest respect or repentance. In addition to the religious context, which we will now discuss, this bow is used to express extreme repentance or during an audience with the emperor. In other words, you shouldn't use it for random people.

standing

Video

- Get into seiritsu position.

- Lean forward for 2.5 seconds.

- At the same time and at the same pace, lower your hands down the front of your legs.

- Leave your hands at knee level.

- Direct your gaze towards the floor at a distance of 80 cm from you.

- Hold this position for 3 seconds.

- Slowly straighten your body for 4 seconds and return to the starting position

Sitting

- Sit in seiza position.

- Lean forward for 3 seconds until your face is 5 cm from the floor.

- At the same time, move your hands down towards your knees, starting with your right hand.

- Place your hands in front of you at a distance of 7 cm so that a regular triangle is formed.

- Form an acute angle in the inner space between your hands, so that your index fingers touch.

- Direct your gaze straight down - your face should be parallel to the floor.

- Your posture should look compact, with your chest lightly touching your hips and the inside of your forearms touching the outside of your knees.

- Stay in this pose for 3 seconds.

- Gradually, over 4 seconds, straighten up into seiza, moving your left hand a little faster than your right.

- Look at the point between you and the interlocutor to whom you just bowed.

When you practice this bow in a sitting position, pay special attention to point No. 9 of returning to the starting position. Do this movement thoughtfully and diligently, taking a short break before straightening up completely. This way, you will visually prolong the bow and show even greater politeness.

Also, since this bow lasts 10 seconds, there are breathing guidelines here. You should bend over as you inhale, then exhale as you remain in a static position with your face parallel to the floor. After exhaling, take a short break and, as you inhale, straighten into seiza.

Nirei-nihakushu: “ritual” bow

When you visit a Shinto shrine, you can make a wish and ring a suzu (special bell). After you do this, you need to bow to nirei-nihakusyu 二礼二拍手(nireinihakusyu).

- Perform 2 keirei bows.

- Clap your hands twice at chest level with your hands pointing upward.

- Perform a saikeirei bow.

Dogedza: bow "request for mercy"

Video

These days, you're likely to only see dogeza 土下座 in yakuza or samurai movies. Someone who is accused of having done something truly unacceptable and unforgivable should do dogeza, hitting his face on the floor, filled with shame or fear. I hope you never have to do this type of bow, because it is essentially groveling and a great humiliation.

Special circumstances

- If you work in Japan, you may find that your company has specific bowing rules that differ from the ones we've outlined here. For example, your superiors may tell you to hold your hands a certain way when bowing or to bow to a certain level. In this case, just follow the instructions and follow the example of your colleagues.

- If you are bowing while sitting on a chair, leave some space between your back and the back of the chair and sit with your back straight. Women should bring their knees and feet together, while men should spread their knees and feet 15-20 cm apart. The angle of inclination is the same as in a standing position.

Too many subtleties?

If you're still confused about when, how deeply, and for how long to bow, here are some quick tips to help you be polite to your interlocutor in Japan without having to learn the ins and outs of bowing etiquette.

First, return your bow with a bow. This applies to all situations, except when you are greeted in a store or when handing out leaflets on the street - then it will look, at least, strange.

Second, when in doubt, bow 30°. It is universal in any situation, as it is the middle link between extreme respect and familiarity.

Third, use knowledge of the other person's age and social status to decide what depth of bow is appropriate. You can save yourself from guessing his age and easily find out the social status of your interlocutor by inviting him to exchange business cards. People in Japan hand out business cards like candy, so this shouldn't be a problem.

If all of the above methods do not work, simply hold the bow a little longer than your interlocutor (politeness is never excessive). If you are in a group, then respond with a longer bow to your immediate superior and observe how he behaves with others, based on the examples you have seen.

What are the common mistakes we make when using bows in Japan?

- Do not place your palms together and against your chest when you bow. Indeed, this is the original form of bowing that came from China with Buddhism, but it is no longer relevant except for religious rituals.

- In a business setting, never bow while walking, even if it is just a greeting. Stop, bow, and then continue moving.

- Bowing while sitting on a chair is also unacceptable in a business setting. A good rule to remember is that if the person you want to bow to is standing, you should also stand.

- Do not talk while bowing. If you have something to say, say it and then bow. This rule is called gosengorei 語先後礼(ごせんごれい) (literally “words first, then bow”). The only exception is when you are apologizing. An apology spoken out loud along with a bow will make it clear to your interlocutor that you are sincerely worried about what happened. But be careful: such an exception to the rules can have unpleasant consequences if your interlocutor is a strict conformist and tries to adhere to standard forms in everything. Just be guided by the situation.

- When you bow while standing on a ladder, do not do so from the top step towards your opponent. Wait until the person you are greeting is on the same level as you.

- Do not bow when it is obvious to the other person that you are angry with him or experiencing other negative emotions. Bowing is a way of showing respect, so every part of your body should convey this message.

- Some men put their hands in the back pockets of their pants when bowing, but this is not the correct form (unless your company has a rule like that). As we discussed earlier, your hands should rest on the front of your legs.

- Some women place their hands at their sides or hold them in front of them, placing one hand on top of the other. This is an incorrect form of bowing, although it has gained popularity among young people, perhaps because it looks more graceful and feminine. This cannot be called a mistake, because culture is a living and constantly changing phenomenon, just remember that this is a non-traditional form of bowing.

Other fun facts about the role of bowing in Japan

We must warn you that once you start using bows, it will be difficult for you to stop! In this part, we have collected for you some everyday situations in Japanese life that may seem quite unusual to you.

Japanese style of bowing over the phone. Bowing has become such a part of the everyday life of the Japanese that they often bow, for example, when talking on the phone, that is, when the interlocutor cannot even see them. Usually in such cases they use a bow-nod, but some people go further. If you find yourself bowing during a phone conversation, it means you've spent enough time in Japan.

The Japanese custom of bowing to the train. If you have ever waited at a station for your Shinkansen, you may have noticed men and women there bowing to the departing train as it leaves the platform. Usually such people are employees of a transport company, stewards or cleaners, such a gesture shows their gratitude towards customers.

Video

You will also see people bowing to elevators in shopping malls. This is dedication!

Video

Who bows last? As you may have noticed, politeness is something of an art form in Japan. Sometimes it can also be a competition, especially between people of the same social status and social position. When two such people bow to each other, they will often be forced to return every bow the other person makes. "ABOUT! “He bowed,” one will think, “I better bow again!” The interlocutor, seeing this, will say to himself: “Oh, no, he bowed again, so I will have to bow again too!” This leads to them bowing to each other repeatedly, making the bow less profound each time. Eventually, when the bows become so small that they cannot even be identified as bows, they may stop and go their separate ways. The point is that no one wants to be thought of as not showing enough humility and respect.

We hope that the article we have prepared for you was interesting and informative, and now you will feel a little more confident the next time you communicate with Japanese people. If you still have any questions about how to bow correctly in Japan, write in the comments and we will try to answer them.

We recommend:

In transport

In Japan, there are several important rules of conduct in public places, including transport:

- You cannot shout (you should not loudly call out to a person in a crowd, even if it is someone you know).

- You can’t be rude and respond to pushes (people push and step on feet in public transport often (imagine the passenger flow of the Tokyo subway), but no one breaks down or makes a row, everyone tolerates it).

- You cannot talk on a mobile phone at a station, stop, and especially on a train - this disturbs the peace of other passengers and is considered the height of incivility (everyone writes SMS).

- You cannot board a carriage for women if you are a man (in the evenings, on some lines, trains run with carriages intended only for female passengers, in order to protect them from harassment during the crush).

- You can't blow your nose in public.

- You should not give up your seat to grandmothers (there are special seats for pensioners and disabled people, which no one would think of occupying illegally).

Japanese people don't talk on the phone on public transport.

Japanese etiquette: National characteristics

Japanese etiquette is a complex “science”. Its origins lie in Confucianism, Shintoism, and the strict hierarchical system of Japanese society.

The Japanese are almost always polite and calm. They understand that it is difficult for a European to adapt to their culture, and they treat mistakes in the behavior of tourists with kind irony. That is why a foreigner’s knowledge of Japanese traditions evokes genuine respect from them.

Bowing in Japan

In this country it is customary to bow everywhere, but the Japanese bow differently. For example, bowing to the emperor just 15 degrees is a great insult. How to understand Japanese bowing etiquette? Is it necessary to bow to waiters in restaurants and hotel staff? Imagine, the Japanese bow, even just when talking on the phone - they have absorbed bows so much since their mother’s milk.

So, the duration and depth of the Japanese bow can be different. Moreover, the depth of the bow should be directly proportional to the status of the interlocutor. A nod of the head is enough for a friend, a boss deserves a bow of about 45 degrees, but an elderly person receives 70 degrees. However, since you are a gaijin, you can get away with just bowing your head or bending a little at the waist.

By the way, tourists are not required to bow to hotel staff, taxi drivers, waiters and shop assistants, since they pay for their services.

Magic words

Addressing your interlocutor

Nihongo no keisho are noun suffixes used in communication and added to a person's first name, last name, or profession. They indicate the degree of closeness of the interlocutors and the social connections between them. Addressing without a suffix is rude. It is permissible only in communication between schoolchildren, students and close friends, as well as when an adult addresses a child.

Basic nihongo no keisho: -san - used in communication between people of equal social status, younger to older, as well as unfamiliar people, to show discreet respect (something like our “You”); -kun – used in informal communication between colleagues, friends, as well as to address a senior to a junior (a boss to a subordinate); -chan - used in close communication between people of equal social status and age, as well as as an address to children (something like diminutive forms in Russian); -sama – used to express extreme respect, usually in official letters (something like “sir”); -senpai - used when a younger person addresses an older person (teacher - student, less experienced employee - more experienced); -kohai – reverse “-senpai”; -sensei – used when addressing scientists, doctors, writers, politicians and other persons respected in society.

Views

Looking into the eyes of your interlocutor for a long time is considered a sign of aggression in Japan. There is another interesting point: if the interlocutor looks away for too long, they may think that he is hiding something or lying. Therefore, you need to maintain a golden mean between a modest downward gaze and an unwavering gaze.

Requests

To ask for help, you need to say “onegai” or “kudasai”. But in Japan it is not customary to ask (only in the most extreme cases). Therefore, refusing help is not rudeness, but, on the contrary, a sign of respect. You can only accept someone’s support when the person expresses their willingness to help several times in a row.

Apologies

Common words of apology are “Gomen nasai” and “Sumimasen”. The latter is translated literally as “there is no forgiveness for me” and is used very often. This is how the Japanese show how much they respect their interlocutor who has been inconvenienced in some way.

Language of the body

Words are secondary to the Japanese. They express a lot (if not all) in sign language. The main rule in communicating with the Japanese is that personal space must not be violated.

When talking to someone you don't know, keep your distance. No familiar pats on the shoulder or hugs, no intrusion into your personal comfort zone.

Runny nose

If you have a runny nose in Japan, then you will have to become a real ninja and master the art of quickly hiding from others before using a handkerchief (which is not accepted here) or a special napkin. But sniffling - even during a business meeting - is quite normal, and no one will judge you for it.

Collectivity

In general, it is considered indecent not only to blow your nose, but also to attract undue attention to yourself in any way - speaking loudly or communicating on a mobile phone in public transport. Any schoolchild in the Land of the Rising Sun will tell you that there is no worse misfortune for a person than individuality, and the most important thing in life is the collective. And he will immediately run away to his own people.

What you need to know about a Japanese house

When entering a Japanese house, you must take off your shoes. For you and me there is nothing strange in this, but Europeans and Americans often make mistakes with this.

The oddities begin further: you should take off your shoes when entering the office. Both in the office and at home you will be offered special slippers. However, even in these slippers, no one living dares to step on the tatami - otherwise you will definitely provoke the wrath of the dragon! When entering a room covered with these mats, you should take off your shoes completely.

Shoes

Here a catch awaits the foreigner. In America and Europe, it is not customary to take off your shoes when entering a living space. This is mandatory in Japan.

Entering a house with shoes on is a gross violation of Japanese etiquette. The Japanese forgive many mistakes made by inexperienced foreigners, but not this one. Sometimes you will be offered slippers, sometimes not. Here the second catch awaits the guest - always make sure that your socks are clean and intact.

The third catch was lurking near the restroom. Near the entrance to the bathroom or toilet in a Japanese house there are another, special slippers (most likely even flip-flops, with special inscriptions). “And let them stand,” the foreigner will think and cross the threshold in slippers or barefoot, thereby risking exposing himself to ridicule. To use the restroom, you must change your shoes.

Away

The Japanese rarely invite guests (especially foreigners) into their home. And it's not a matter of inhospitality. Just your own house, not a rented one, is a rarity, and its area leaves much to be desired. If you receive an invitation to come visit, you are greatly honored. It is extremely impolite to refuse.

Present

You cannot go on a visit empty-handed. Gifts are an important part of Japanese culture. They are given for holidays, on special occasions, as a sign of respect, etc. Symbolism and ceremony are very important. There is even a special term “Zoto” - the art of giving gifts.

Basic rules for giving gifts:

The gift must be wrapped. A gift (like any other thing solemnly passed from person to person) should be given and received with both hands. You should not immediately unpack a gift (a sign of curiosity and greed). The gift should be practical and appropriate for the occasion (money is often given). The gift should not include the number 4 (a homophone of the hieroglyph for death). You should “apologize” for a gift (even if it is very expensive) (your modest gift still cannot express the respect that you have for the recipient). It is customary to write letters of gratitude in response to a gift received by mail.

So, according to the rules of Japanese guest etiquette, upon entering the house, the guest must stop in the hall (“chenkan”), where the hosts will meet him. The guest must present the gift to the hostess and apologize for disturbing them with his visit. The hosts, in turn, apologize for receiving the guest so modestly. After such an exchange of pleasantries, you can enter the house.

Feast

At the table in Japan, it is customary to sit on the tatami in the seiza position: legs tucked under oneself, back straight, like reeds on Lake Mashu. Men can simply sit “Turkish style” - in the agura position, but only with friends or relatives. A woman is only allowed to move her legs slightly to the side when sitting in seiza, and then only if she is a foreigner.

But stretching your legs, and even more so sitting so that your socks point at someone present or, Buddha forbid, these socks touch them - even the fact that you are a gaijin will not save you.

Touching a Japanese man with the lowest point of his own body is a terrible insult akin to the one for which Bill was killed.

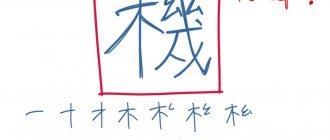

Khasi

Hashi is the name for Japanese chopsticks. Some Japanese are still surprised when they see how easily foreigners can handle them. If only they knew how many sushi bars there are in one Russian quarter...

If you still don’t speak hashi very well, then don’t be afraid to seem funny or clumsy - even the Japanese are not all friends with this device. However, there are a few things that you absolutely should not do with hashi.

What not to do with hashi

Chopsticks are not just a cutlery, but also a part of culture and history. That is why there are special etiquette and unspoken rules for using chopsticks.

Mayobashi is strictly prohibited! Simply put, you cannot draw with chopsticks on the table or point at something with them.

Sashibashi - under no circumstances! You can't pierce food with chopsticks. If all else fails, then in a circle of close friends, men can take sushi with their hands, and women can move their legs a little more to the side.

Tatebashi is even more impossible. If you stick chopsticks into a bowl of rice, this is for the deceased... because it is reminiscent of the sticks of incense that are given to deceased relatives.

Saguribashi is also not allowed! It is considered bad form to touch a piece of food with chopsticks and not take it.

In Japan, utensils are handled only with your hands, so you should not move the utensils with chopsticks.

Do not clench your chopsticks into your fist, as the Japanese may perceive this as a threatening gesture!

The Japanese also attach great importance to symbolic meanings, so they should not put food with chopsticks on another person’s plate, because this reminds them of transferring the bones of the deceased to close relatives after cremation in an urn.

After finishing a meal, in Japan it is customary to place the chopsticks on a stand, on the table, or on the edge of the plate, but you should not place the chopsticks across the cup.

Other table rules

The meal begins only after the word “Ittadakimas”. This is such an abbreviated version of the prayer, meaning approximately “let us eat what is given.” If no one says it, and you’re already pretty hungry, you can say it yourself, just don’t forget to fold your hands palm to palm.

You shouldn’t just start drinking either. First, one of those present must make a toast ending with another magic word - “kampai”. This is an analogue of our “drink to the bottom”, but it is not necessary to understand it literally...

Drinking to the bottom is dangerous. As soon as the pourer sees an empty glass, he will immediately fill it. By the way, if you pour the drinks, then fill your glass last. End of the meal

It is bad form to leave the table silently. You must definitely thank the one who fed you (the owners of the house, the chef of the restaurant), even if he does not hear you. To do this you need to say “Gochisosama”. A couple more tips

Don't be surprised by loud smacking at the table - this is how the Japanese express pleasure from food. Don't try to tip - it's not accepted.

In transport

In Japan, there are several important rules of conduct in public places, including transport:

You cannot shout (you should not loudly call out to a person in a crowd, even if it is someone you know). You can’t be rude and respond to pushes (people push and step on feet in public transport often (imagine the passenger flow of the Tokyo subway), but no one breaks down or makes a row, everyone tolerates it). You cannot talk on a mobile phone at a station, stop, and especially on a train - this disturbs the peace of other passengers and is considered the height of incivility (everyone writes SMS). You cannot board a carriage for women if you are a man (in the evenings, on some lines, trains run with carriages intended only for female passengers, in order to protect them from harassment during the crush). You can't blow your nose in public. You should not give up your seat to grandmothers (there are special seats for pensioners and disabled people, which no one would think of occupying illegally).

By the way…

According to the experience of numerous Japanese tourists, their behavior abroad often causes indignation or grinning among foreigners.

In order to avoid inappropriate behavior while traveling, Japanese tour operators have compiled a list of cultural differences and, as a result, things that residents of the Land of the Rising Sun should avoid.

Thus, the main aspect that causes hostility among foreigners is sipping while eating, while in Japan this is not only acceptable, but also encouraged: the Japanese believe that sounds at the table show approval of a delicious dinner and praise for the owner.

Next on the list is photography: most disapprove of a stranger's decision to capture them on camera, drawing an analogy to an animal in a zoo; others are fine with this, adding, however, that they would not mind if they were asked first. Japanese tourists are famous for their love of photography - it is natural for them to capture any passerby they catch their eye.

Also, tour operators in Japan say that arriving at a meeting ten minutes in advance is considered late in the country, while in Europe and the USA, arriving too early will be regarded as an insult to the hosts, because by doing so the guest puts them in an awkward position. Thus, for at least thirty minutes the Japanese will be the only guest in the house.

Japanese people are being urged to avoid chewing gum in Singapore, where it is considered an insult. Hygienic procedures, such as blowing your nose at the table, are considered a common natural thing for Japanese residents - the British express the greatest indignation on this issue.

As you can imagine, these rules are just the tip of the massive iceberg of Japanese etiquette. On which, perhaps, cherry blossoms...

Source: russiahousenews.info, lifehacker.ru

At the table

Start of the meal

Before the start of lunch (according to the classical canons), a damp hot towel is served to clean the hands and face - “oshibori”. But if you eat at a regular restaurant, there may not be oshibori.

But wherever you eat, before you start eating, you need to say “Itadakimasu” (I accept this food with gratitude). This is instead of "bon appetit."

As for the sequence of dishes (again, in a traditional lunch), you should first try the rice, then the soup, and only then try any other dishes.

Sticks

Khasi are traditional chopsticks. Hasioki is a stand for them. The ability to use chopsticks correctly is an indicator of a person’s culture.

There are a number of strict taboos against the Khasis. Read more about this in the material “How not to use chopsticks.” [new_royalslider id=”94"]

Toasts

"Kanpai!" - this is what the Japanese say, raising a glass of sake (or other alcohol) and clinking glasses. Translated, this means “Drink to the bottom!”

But drinking to the bottom is dangerous. As soon as the pourer sees an empty glass, he will immediately fill it. By the way, if you pour the drinks, then fill your glass last.

End of the meal

It is bad form to leave the table silently. You must definitely thank the one who fed you (the owners of the house, the chef of the restaurant), even if he does not hear you. To do this you need to say “Gochisosama”.

A couple more tips

- Don't be surprised by loud smacking at the table - this is how the Japanese express pleasure from food.

- Don't try to tip - it's not accepted.

Bowing as a means of expressing respect for your interlocutor

Master the Japanese language # learn Japanese quickly # Japanese textbooks for the Japanese language # Japanese teachers at the Japanese language center # fall in love with the Japanese language #

Bowing among the Japanese is a universal non-verbal form of etiquette, which, depending on the situation, can express greeting, congratulation, request, apology, and obedience. Probably, the habit of bowing is associated with the need to demonstrate humility and submission by bowing the head or kneeling in order to avoid conflict with a stronger opponent. Bowing has become a recognized form of expression of submission in religious communities. The Japanese expanded their understanding of the bowing ritual, brought it to the level of art, and even went further. In Japanese society, bowing even took the form of non-alternative communication. In the Middle Ages, if a bow was made at the wrong time or in the wrong form, it could cost a person his life. Therefore, children begin to be taught the art of bowing before they learn to walk and begin to master the basics of the Japanese language. Even today, Japanese children are taught to make traditional bows throughout the day in kindergarten and school.

How to remember Japanese characters # secrets of learning Japanese # Japanese language learning center # Master spoken Japanese # be a master of Japanese # Japanese calligraphy and Japanese language #

The Japanese bow to each other several times a day. If a Japanese meets with a senior in age or position, for example, in an institution, then the first time he makes a regular bow, and at subsequent meetings during the same day he only needs to make a slight bow. Greetings and bows are designed to create a favorable atmosphere of communication and harmonize interpersonal relationships. A greeting is a sign of good intentions towards the person to whom it is addressed. According to Japanese speech etiquette, each person must be able to demonstrate his respect for another. So, if you want to sit in a vacant seat on a train, you need to turn to the person already sitting next to you and say in Japanese “shitsurei shimas” (translated from Japanese as “I apologize for sitting next to you”). Japanese speech etiquette requires an initially clear definition of the social status of the participants in communication. Based on this, the forms of verbal communication also differ. Therefore, bowing in Japan is more than a bow, since, among other things, it includes a whole layer of important information to convey to the interlocutor.

Poetry of the Japanese language # hieroglyphic textbooks of the Japanese language # Japanese linguistic center # Read the text in Japanese without a dictionary # Representative office of the Japanese Institute of Foreign Languages in Moscow - teaching Japanese

Japanese etiquette distinguishes four main types of bows:

The most polite bow in Japanese is “saikeirei”. As a rule, they are greeted by especially important people, the top management of the partner company, or they are used when making a request or apology. In this case, your hands should be held in front, along your knees, and your body should be tilted at an angle of 45°.

The usual bow – in Japanese – is “keirei”, which is used to bow at the first meeting or with visitors. The fingers should be strictly extended, and the hands themselves should be strictly along the knees, the body should be at an angle of 30°.

A slight bow - in Japanese - “eshaku”, is not burdened with great social significance. This bow can be used to greet colleagues, acquaintances and friends. The body is at an angle of 15°, the arms are connected in front, the legs are moved together.

A nod and a greeting with a glance - in Japanese - “mokurei”. In accordance with etiquette, you should nod your head while looking into the eyes of your interlocutor. This type of greeting can be used in places with limited space, for example, in an elevator, on an escalator, or if the interlocutor is at some distance.

Japanese language courses in Moscow # Japanese linguistic center # Japanese language learning center # Conversational Japanese language courses # Japanese linguistic center # Japanese center in Moscow

Bows can be performed from three positions: standing, sitting in Japanese or sitting in European style. Most bows also have a female and a male “variety”. When meeting, those younger in age and lower in position bow first and perform the more polite, i.e. lower bow.

According to the degree of politeness, etiquette norms suggest three types of bows:

- Everyday standard or lightweight (≪esyaku≫) with an inclination of up to 15°;

- Standard polite bows (rei, ojigi) with a body tilt of about 30°;

- Ceremonial and respectful (≪saikeirei≫) with an inclination from 45° to 90°.

The importance of bowing in modern society is so great that a foreigner studying Japanese should include this type of non-speech element in his science course.

Japanese language - there is so much in this sound!# I want to learn Japanese# Japanese linguistic center# Explore Japan through the Japanese language# Spoken Japanese for communication

The Japanese Linguistic Center offers to start learning Japanese!

Business conversation

The Japanese know a lot about business. To earn the trust and respect of Japanese partners, you need to know several basic rules of national business etiquette.

Lateness

The Japanese are never late. Making a Japanese wait is disrespectful. It's better to arrive early for a meeting than to be late.

No!

Hearing a direct refusal from a Japanese businessman is nonsense.

The Japanese don't say "No".

Even if they are not completely satisfied with the terms of the deal. Instead, the Japanese will nod and give abstract, evasive answers (“We’ll think about it,” “It’s difficult,” etc.). The origins of this behavior are in “timmoku” (the Japanese art of silence) - it is better to remain silent than to offend a person with a refusal.

If the deal completely suits the Japanese, you will hear a clear and unambiguous “Yes”.

Business cards

The exchange of business cards is an important ceremony in Japanese business communication. Firstly, a business card is a kind of cheat sheet (the Japanese have difficulty with European names, just like we have Japanese ones). Secondly, the position is indicated on the business card, which allows you to choose the right course of action. Thirdly, it is a sign of respect from your partner.

A business card, like a gift, is handed over with both hands.

Business cards are exchanged at the first meeting during the greeting. They are passed and received like a gift, with both hands. The business card should be neat, printed on good paper, the text should be written in (at least) two languages – Japanese and English.

If you go to a foreign country, follow its customs. Japanese proverb

Japanese etiquette is complex and sometimes incomprehensible. The above is just the tip of the iceberg. If you know other secrets of Japanese etiquette, share them in the comments.

from Journeying.ru

Bowing (o-jigi) is probably a feature of Japanese etiquette that is well known outside the country. "O" is an honorific prefix, but it cannot be omitted under any circumstances. O-jigi is part of everyday life. By bowing, people greet each other, congratulate, apologize, thank, say goodbye, and so on. In modern Japan, handshakes, akushu, have become widespread as a form of greeting, but many Japanese, especially the older generation, still cannot get used to them. Handshakes are common between Japanese and foreigners, at special events, and meetings between public figures.

The Japanese have been taught the art of bowing since childhood; many companies provide their employees with the opportunity to learn how to bow correctly in special courses. The longer and deeper the bow, the more a person tries to express the degree of respect that he feels for his interlocutor; he may be senior in age or occupy an important position. Bowing has been a way of showing respect to another person for centuries in East Asia. In general, bows can be divided into three main types - informal, formal and extremely formal. Greetings between friends may be accompanied by a nod of the head (“eshaku”) and a raise of hands, as if in passing.

Men bow with their arms extended to their sides and their palms pressed to their bodies. They tilt their heads slightly to the left (so as not to hit their heads). Women – arms crossed in front of themselves. If they are sitting on a chair, they stand up to bow. If you are sitting on a zabuton, then stand slightly with the zabuton and bend over, placing your hands forward. When bowing, they do not look each other in the eyes.

They say that after living in Japan for some time, a foreigner begins to bow automatically and even when talking on the phone, as most Japanese do. Apologetic bows are deep and last much longer than regular bows. When apologizing, a person can bend over several times, bending 4 degrees.

Dogedza is the highest degree of absolute respect or extreme submission. In the past, dogeza (“prostrate”) was considered a formal bow, but these days it is explained as complete self-contempt and is not used in everyday life. The Gishiwa Jinden, the oldest Chinese historical account of encounters with the Japanese, mentions bowing customs in the Land of Yamatai (Yamatai koku). If a simple person met a nobleman on the road, then he fell in front of him on the spot, while folding his palms as if for prayer (= kashiwade). This is a very old Japanese custom, as evidenced by the oldest artifacts, haniwa (funerary ceramic figures) from the Kofun period. However, there is such a term as “dogeza-gaiko” - flattering diplomacy or servile foreign policy.

In extreme cases, a person can kneel and bend so that their forehead touches the ground. This bow is called saikeirei (the deepest or most respectful bow).