Writing systems of Japan on Igor Garshin's website. Japanese writing

print version

| home |

| Write |

Home > Linguistics > Scripts > Far Eastern hieroglyphics > Japanese script

Alphabetical list of pages: | | | | | E (Yo) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 0-9 | AZ (English)

Chinese writing was borrowed to write Japanese words. In addition, a fairly complete syllabary alphabet (syllabary) has been developed and is used in Japan. At the same time, many Chinese logograms denoting Japanese words continue to be used in the Japanese language. Syllabic marks are used mainly with these logograms to express the grammatical elements of the Japanese language.

Sections of the page about Japanese writing systems :

- Chinese characters in Japanese (kanji)

- Japanese alphabet Hotsuma-tsutae (unknown authenticity)

- Katakana - syllabary for children and transliteration

- Hiragana - syllabary for Japanese affixes

- Japanese Writing Resources

Read about the Japanese language and modern Japanese writing on the Japanese Language page.

Pictures-plates for two channels are taken from the magnificent site Ancient Scripts

, which is already closed. But, of course, you can view it in the web archive.

Chinese characters in Japanese (kanji)

As I understand it, the Japanese learn their characters using slightly different methods than the Chinese. And their school minimum is different. It's called kyo:iku kanji

教育漢字 (“educational kanji”).

This is a list of 1006 characters (and their readings) that Japanese children learn in elementary school. Full name: Gakunenbetsu kanji haito:hyo: 学年別漢字配当表

(“list of kanji by year of schooling”). The list is developed and maintained by the Japanese Ministry of Education, which determines which kanji Japanese children will learn in each year of primary school. Although the list is specifically made for Japanese children, it can be used as a set of kanji for foreigners to learn the language at an early stage, in order to limit the number of kanji to the most used ones.

The list was first established in 1946 and contained 881 hieroglyphs, in 1977 it was expanded to 996, in 1981 it was expanded to the modern number (1006 hieroglyphs). Their study is distributed over 6 levels: 1 - 80 kanji, 2 - 160, 3 - 200, 4 - 200, 5 - 185, 6 - 191.

- Kanji SITE (Russian-Japanese dictionary of hieroglyphs)

- List of educational kanji (6 levels).

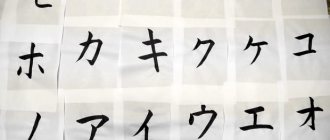

"Four Jewels of the Cabinet"

This is how calligraphy masters respectfully called the four main “tools” of ancient China. The craftsmen paid great attention to the selection and careful use of these items. These are: 1. Brush . 2. Inkwell . 3. Mascara . 4. Calligraphy paper

Masters of calligraphy in modern Japan, where this ancient art has found a new lease of life, use the following six items:

- Shitajiki : black, soft mat.

- Buntin : a metal used to press down paper while writing.

- Hansi : A special, thin writing paper traditionally made from rice straw. This is usually Washi , a traditional handmade Japanese paper.

- Fude : brush. There is a large brush for writing large characters and a small one for writing the artist's name.

- Suzuri : heavy, black ink container.

- Sumi : “writing ink” is a hard black material into which water is rubbed to produce ink, into which a brush is then dipped.

Mastering calligraphy includes: 1) learning the basic skills of writing in different stylistic manners; 2) the history of calligraphy and the theory of hieroglyphs; 3) acquaintance with traditional Japanese culture and language through calligraphy.

Japanese alphabet Hotsuma-tsutae (unknown authenticity)

| a | ka | ta | ha | sa | ma | na | ra | wa | ya | Supposedly ancient Japanese alphabet hotsuma-tsutae , which was used even before the introduction of hieroglyphs from China and the appearance of other Japanese alphabet. In fact, the appearance of the signs is very similar to simplified hieroglyphs (a complex of traits and the technique of connecting them). There is an opinion that this is “the same Veles Book.” Maybe “that”, but that’s not the main thing. This alphabet is built according to a clear system, its internal logic is admirable. If someone came up with it recently, “a flag in the hands” of this talented pasigrapher. On the basis of this syllabary system, it is possible to create a truly masterpiece not only of international writing, but also of an international language based on this writing, if each type of trait is assigned its own semantic “archetypes”. It can also be developed simply as a compact writing or shorthand, by developing an equally harmonious system for connecting a larger number of phonemes.

|

| o | ko | to | ho | so | mo | no | ro | wo | yo | |

| e | ke | te | he | se | me | ne | re | ye | ||

| u | ku | tu | hu | su | mu | nu | ru | wu | yu | |

| i | ki | ti | hi | si | mi | ni | ri | yi |

see also

- Genko Yoshi (graph paper for writing in Japanese)

- Iteration mark (Japanese duplication marks)

- Japanese typographical characters (characters without kana and kanji)

- Japanese Braille

- Japanese language and computers

- Japanese manual syllabary

- Chinese writing system

- Okinawan writing system

- Kaida glyphs (Yonaguni)

- Ainu language § Writing

- Siddhaṃ script (Indian alphabet used in Buddhist scriptures)

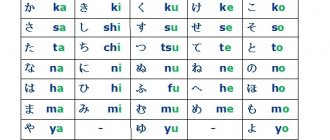

Katakana - syllabary for children and transliteration

Online resources for katakana:

|

In one book I read a recommendation to study hiragana first, then katakana. But for me personally, it’s more effective exactly the other way around, because... It is difficult to find mnemonic images for ornate hiragana characters, but easy to find for simpler katakana characters (at least for half of the characters). Oh, because Some of the signs of both kana are mutually similar, then after quickly mastering the “kata” it will be easier for you to start memorizing “hiru”.

Here are my mnemonics in katakana (at first I came up with it myself, then I borrowed successful mnemonics from Stout’s book):

- ワ va - VALIK; Valenok; Wow!

- ラ ra - the crayfish is boiling (lifting the lid); robber (masked)

- I ヤ - “Yes, it’s ME!”; Fury bursts from the chest; scimitar

- ma マ - tangerine seed; sail on the mast

- ha

ハ - robe wide open; WAVE - na

ナ - insect, string; our hanger (stuffed animal, knife); cross - ta タ - slipper; that Leaning Tower of Pisa

- sa サ - sled on top; barn (its door or fence nearby); Bench (without K)

- ka

カ - KATANA, POCKET; like (without top line) - a ア - stork on the roof; rock

- ri リ - rice shoots, marks (serifs, dashes)

- mi ミ - sweet stroke :); mustache of a CUTE cat; three flashes

- hee ヒ - the sly one giggles while driving

- ni

ニ - two threads, ni = 2 - ti チ - quiet in the churchyard; target at the shooting range; crossed out DASH; Tiger striped on top

- si シ - tits :), cigarettes in the palm of your hand; beautiful smile

- ki キ - brush; mast at KIL; throw

- and イ - i with a bar; music stand; ibis stands

- ru

ル - HANDS; RUslo; Such roots cannot be cut down quickly - yu ユ — yulu launchYu (pressYu); funny gallows without rope

- mu ム - sift flour with a sieve

- fu フ - “Fu, sharp angle!”

- well ヌ — ; Well, seven!

- tsu ツ - zucchini, candied fruits (?); tsunami (with 2 drops)

- su ス - stern judge in a hat

- ku ク - ; SECOND, short seven

- u

ウ - iron - re レ - cut with a knife; RIVER meander; raindrops perform rap

- me メ - sword

- he ヘ - hill starting with the letter He; HuangHe bend

- ne

ネ - NEtsuke - te

テ - letter TE; telephone - se セ - ; sandwich

- ke ケ - Kat; kangaroo

- e エ - eras; these (elevator) doors, this press

- o ヲ - ; Yell with your mouth open and your tongue hanging out

- ro ロ - quadRO music; square mouth; ROBOT head

- ё ヨ - letter Ё inverted; shelves with YOGURT

- mo モ - BRIDGE (section with a pile); skein of thread; can be baited on a hook

- ho ホ - mansions; laughter to tears

- but ノ - But!, stretch out your ACHING back; horse (dog) nose, dorsum of the nose

- to

ト - TOpor, poplar - so

ソ - SOkha; sleep with a smile - ko

コ - box on the side - o

オ - axis; Aspen, Alder, hazel; experienced figure skater (dancer) - n ン - nose with a smile;

It should be noted that some katakana signs are quite similar to each other, differing only in the inclination of the strokes, and, at first, you can make a mistake when you see them. Also, these syllabems can differ by only one line. Therefore, I grouped them into the following groups of similarities, so that the differences can be seen more clearly and remembered in groups, perhaps it will be easier:

- oblique with or without 1-2 dashes: ノ but; ン n, ソ so; シ si, ツ tsu

- stick with a branch: ア a (similar to ヤ i and マ ma), イ i, ト that; (it’s close here ヒ hee)

- stick with crossbar (crooked crosses and swords): ナ na, メ me, ヤ ya, セ se (like ヒ hi)

- complicated crosses: オ o, ホ ho; ネne

- stick with 2 crossbars (double cross): モ mo, チ ti (close to テ te), キ ki

- a pair of sticks (ski tracks): ハ ha, リ ri, ル ru (also close are the one-and-a-half sticks レ re and the crossed two-fingers サ sa and カ ka)

- rotated G with features (left quasi-F): ユ yu (close to エ e), コ ko (close to ロ ro), ヨ yo (similar to ミ mi)

- curves turned G with lines, branches, crossbars: フ fu, ラ ra, ワ wa; ウ u, ク ku, ケ ke; ヲ o, ヌ well (close タ ta), ス su

- ム mu and ヘ he remained outside the groups.

Content

- 1 Using scripts 1.1 Kanji

- 1.2 Hiragana

- 1.3 Katakana

- 1.4 Ramaji

- 1.5 Arabic numerals

- 1.6 Hentaigana

- 1.7 Additional mechanisms

- 1.8 Examples

- 1.9 Statistics

- 5.1 Kanji import

- 6.1 Label styles

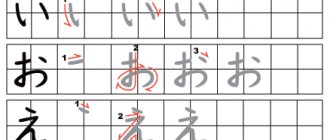

Hiragana - syllabary for Japanese affixes

Online resources for katakana:

|

Let’s try to come up with images for memorization for hiragana, and, first of all, these will be similar katakana signs, for which images have already been invented:

- あ a

- い and

- うу

(Ear) - え e

- お about

- ゃ I am cat. ヤ (rage from the chest)

- ゅ yu (and similar to Yu)

- ょ ё (Christmas tree after the holiday)

- か ka - cat. カ (katana)

- き ki (English key [ki:] - key) - cat. キ (~ BRUSH)

- く ku (2 right strokes K without the stick itself, or angular C)

- け ke (kent)

- こko (claws)

- きゃ kya

- きゅ kyu

- きょ kyo

- さ sa (samurai sitting in seiza) {present in the honorific postfix -san}

- しsi

- す su; {included in the narrative ending -mas and in the ending -des “is, is”}

- せ se - cat. セ (sandwich)

- そ with

- しゃ xia

- しゅ syu

- しょ sho

- た that

- ち ti

- つ tsu (tsunami)

- て te (as in Greek tau);

- と then; {joint case}

- ちゃ cha

- ちゅ tu

- ちょ cho

- な on

- に ni (thread); {dative-accumulative-transformative case and places of condition}

- ぬ well

- ね ne

- の but (like the ampersand @

); {possessive} - にゃ nya

- にゅ nude

- にょ no

- は ha {at the end of a noun - -wa - thematic case}

- ひ hi (sly nose)

- ふ fu

- へ he {after a noun - e - directive case} - cat. ヘ (HuangHe Hills)

- ほho

- ひゃ hya

- ひゅ hyu

- ひょ hyo

- ま ma; {part of the narrative ending -mas}

- み mi (cute horse)

- む mu (fly over the nose)

- め me (the ram tilted his head: meh!)

- も mo - cat. モ (skein of thread; can be crocheted); {adjunctive case}

- みゃ me

- みゅ mu

- みょ myo

- や I

- _

- ゆyu

- _

- よ ё

- _

- ら ra

- り ri - cat. リ (2 marks)

- る ru

- れ re

- ろ ro

- りゃ rya

- りゅ ryu

- りょ ryo

- わ va

- ゐ vi

- _

- ゑ ve

- を in / o {after a noun - o - accusative case}

- ん n

- がha; {rhematic case}

- ぎ gi

- ぐ gu

- げ ge

- ご th

- ぎゃ gya

- ぎゅ gyu

- ぎょ gyo

- ざza

- じ ji

- ず zu

- ぜze

- ぞ dzo

- じゃ jia

- じゅju

- じょ jo

- だ yes

- ぢ (ji)

- づ (zu)

- でde; {creative locative case (tool or place of action); and at the end -des “is, is”}

- ど to

- ぢゃ (ja)

- ぢゅ (ju)

- ぢょ (jo)

- ば ba

- びbi

- ぶbu

- べbae

- ぼbo

- びゃ bya

- びゅ byu

- びょ byo

- ぱ pa

- ぴpi

- ぷ pu

- ぺ pe

- ぽ by

- ぴゃ pya

- ぴゅ pyu

- ぴょ pyo

Further, as for katakana, hiragana syllabic characters can also be divided into groups according to the similarity of their outlines (but the groups are small, usually pairs):

- あ a, お o; ゐ vi; わ va

- い and, こ ko

- に neither, た ta

- そ so, ろ ro, る ru; ゐ vi; わ va

- つ tsu, う u

- さ sa, ち ti

- ぬ well, ね ne; る ru; ゐ vi

- の but, め me, ぬ well; ねne

- さ sa; き ki; ま ma, ほ ho

- け ke, は ha

The most important hiragana syllabems [in my opinion] are conveying grammatical affixes (highlighted above in red), primarily case postfixes: monosyllabic -wa, -ga, de-, -e, o-, -ni, -no, -mo , -to and two-syllables -made (まだ) - extreme [achievement] case, -kara (から) - initial case, -yori (ょり) - comparative case.

Writing difficulties

The Japanese language has a very limited number of sounds. Besides the fact that it does not have an "L", very few consonants can be mixed together, and each syllable must end with a vowel or N. Because of this, the Japanese language is filled with words that are pronounced the same but have different meanings.

In fact, there are so many homonyms that without kanji it's hard to tell which one you're talking about. Of course, you could write " koutai " in hiragana asこたたい, but "koutai" can mean "replacement", "antibody" or "retreat". Because of this, if you want to get your point across, you're much better off using the kanji, 交代, 抗体, or 後退 to clarify which kotai you're writing about.

- Japanese writing generally does not put spaces between different words. It sounds like it could turn every sentence into a confusing mass of frozen language fragments , but written Japanese tends to fall into patterns in which kanji and hiragana alternate, with kanji forming the base vocabulary and hiragana giving them grammatical context.

For example: “Watashi ha kuruma wo mita,” or “I saw a car,” written with the usual mixture of kanji and hiragana.▼

Right away we can see the kanji-hiragana-kanji-hiragana-kanji-hiragana pattern, which quickly tells us that we have three main ideas in the sentence.

- 私は: Watashi (I) and ha (subject marker)

- 車を: kuruma (car) and wo (object marker)

- 見た: mi– (verb “to see”) and – ta (marking the verb as past tense)

Without the combination of kanji and hiragana, these breaks would be much more difficult to detect. This is what it would look like in hiragana only.

▼ Writing all text in Hiragana also takes up much more space.

Suddenly it becomes much more difficult to tell where one idea ends and another begins, since it is all one continuous thread of hiragana. Trying to read something written only in hiragana is like trying to read “ solid text with no spaces .”

However, the rhythm that comes from combining kanji and hiragana makes written Japanese a clear way to communicate ideas rather than a mad dash to the finish line.

Sources

- Gottlieb, Nanette (1996). The Politics of Kanji: Language Politics and Japanese Writing

. Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0512-5. - Habein, Yaeko Sato (1984). History of Japanese Writing

. University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 0-86008-347-0. - Miyake, Mark Hideo (2003). Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction

. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-30575-6. - Seely, Christopher (1984). "Japanese Writing Since 1900". Visible language

.

XVIII. 3

: 267–302. - Seely, Christopher (1991). History of Writing in Japan

. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2217-X. - Twine, Nanette (1991). Language and the Modern State: Reform of Written Japanese

. Rutledge. ISBN 0-415-00990-1. - Unger, J. Marshall (1996). Literacy and Writing Reform in Occupied Japan: Reading Between the Lines

. POU. ISBN 0-19-510166-9.

Recommendations

- Serge P. Shokhov (2004). Advances in Psychological Research

. Nova Publishers. paragraph 28. ISBN 978-1-59033-958-9. - Kazuko Nakajima (2002). Learning Japanese in a Networked Society

. University of Calgary Press. paragraph xii. ISBN 978-1-55238-070-3. - "List of Japanese Kanji". www.saiga-jp.com

. Retrieved 2016-02-23. - “How many hieroglyphs are there?” japanese.stackexchange.com

. Retrieved 2016-02-23. - "How to Play (and Understand!) Japanese Games." GBAtemp.net -> Independent Video Game Community

. Retrieved 2016-03-05. - Joseph F. Kess; Tadao Miyamoto (January 1, 1999). Japanese mental lexicon: Psycholinguistic studies of kana and kanji processing

. John Benjamin Publishing. paragraph 107. ISBN 90-272-2189-8. - Richard Bowring and Peter Kornicki, eds.

,

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 119-120. - Chikamatsu, Nobuko; Yokoyama, Shoichi; Nozaki, Hironari; Long story short, Eric; Fukuda, Sachio (2000). "Frequency List of Japanese Logographic Characters for Cognitive Science Research." Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers

.

32

(3):482–500. Doi:10.3758/BF03200819. PMID 11029823. S2CID 21633023. - ^ a b

Miyake (2003: 8). - Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2002). 韓国人の日本偽史 — 日本人はビックリ! (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-402716-7.

- Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2007). 韓 vs 日「偽史ワールド」 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-387703-9.

- Twine, 1991

- Seeley, 1990

- Hashi. "Hentaigana: How the Japanese Language Went from Illegible to Legible in 100 Years." Tofugu

. Retrieved 2016-03-11. - Unger, 1996

- Gottlieb, 1996