What is Shintoism

The Shinto culture originates thousands of years ago - at the advent of a new era. In a sense, it can be called the oldest religion known to us, which has its adherents in modern times.

Formed on the basis of animistic ancient beliefs, Shintoism has now retained many of the features characteristic of primitive societies. This distinguishes it from other cultures where the animistic stage was passed and forgotten a long time ago.

Having absorbed some knowledge from neighboring religions, Shintoism was finally established by the 8th century. The main characteristic of religion can be called its teaching about the spiritual nature of all things.

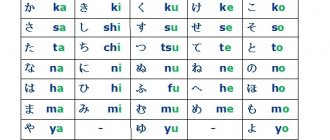

The name "Shintoism" comes from the word "Shinto", which means "sacred way" or "way of the gods" ("way of the kami"). It is noteworthy that Eastern religions are characterized by the metaphor of the path. Buddhism and Taoism also turn to this symbol.

Shintoism is an ancient Japanese religion. Its name comes from the word "Shinto" 神道 - "Way of the Gods." Shinto is based on the worship of all kinds of kami 神 - supernatural beings or spirits. The main types of kami are:

- Creator gods (Izanami and Izanagi, Amaterasu, Susanoo)

- Spirits of nature (kami of mountains, rivers, wind, rain)

- Unusual supernatural phenomena (a tree that is several thousand years old)

- Extraordinary personalities declared kami (Hachiman, Inari, Tenjin)

- Deities borrowed from other beliefs due to their “usefulness” (Daikoku, Ebisu, Jizo)

- Powers and abilities found in humans and nature (say, the kami of growth or reproduction)

- Spirits of the dead.

There are countless deities worshiped in Japan, and each village has a local patron kami. There is no particular division between spirits and ordinary people; on the contrary, there are many myths and legends about marriages between people and kami. The important point is that people (and not only people) were not created by gods, but were born from kami. Death is a transition to the world of spirits, and a child is considered the incarnation of the kami-ancestor ujigami 氏神, therefore in Japan they treat young children with great respect and until the age of five they are allowed almost everything (though then they “tighten the screws” a lot).

Kami are divided into Fuku-no-kami 福の神 ("good spirits") and Magatsu-kami 擬つ神 ("evil spirits"). A person’s task is to call on more good spirits and, if possible, make peace with the evil ones. In principle, good spirits can become evil if they are treated inappropriately and without respect. Therefore, on the islands, in many temples and chapels, parishioners and priests make sacrifices to the gods and pray for help and support. In general, everything that happens in the world in Shintoism is explained by the individual will of the kami, and not by any laws of nature or Fate.

The word "Shinto" 神道 is made up of two characters: shin 神, which symbolizes kami, and to 道, which means path. The corresponding Chinese word "shendao" in a Confucian context was used to describe the mystical laws of nature and the road leading to death. In the Taoist tradition, it meant magical powers. In Chinese Buddhist texts, the word shendao in one case refers to the teachings of Gautama, in another case this term implies the mystical concept of the soul.

In Japanese Buddhism, shendao was used much more widely - to designate local deities kami 神 and their kingdom, and kami meant ghost beings of a lower order than the hotoke 仏 Buddhas. It was largely in this sense that the word "Shinto" was used in Japanese literature for centuries following the Nihon Shoki. And finally, starting around the 13th century, the word Shinto has been used to refer to the kami religion to distinguish it from Buddhism and Confucianism, which were widespread in the country.

Unlike Buddhism, Christianity and Islam, Shintoism does not have a founder such as the enlightened Gautama, the Prophet Muhammad or the Messiah Jesus. There are no sacred texts in it, such as Sutras, the Koran or the Bible. However, there are ancient texts considered authoritative that outline the historical and spiritual foundations of Shintoism.

The oldest surviving monument of Japanese writing, the Kojiki 古事記 (“Records of Ancient Deeds”) or Furukotofumi ふることふみ, dates back to 712 AD. It describes events up to 628. The text is written in Chinese characters, but the writing style is ancient colloquial Japanese, thanks to which you can learn about the style of oral speech that existed earlier and was passed down from generation to generation.

Another text called Nihon shoki 日本書紀 (Brush-written Annals of Japan) or Nihongi 日本紀 (Annals of Japan), which appeared eight years later in 720, recounts events that occurred before 697 of the year. It is written in Chinese and in a different style. This manuscript, unlike the Kojiki, has more details. Some events have mythological explanations and interpretations.

Shintoists value these two documents especially highly, since they contain the only ancient information that has reached us about the imperial family and several clans that gave rise to the Japanese nation. The texts talk about the origin of the imperial throne, the genealogies of some clans, and much more that formed the basis of the social system and traditions of the country. In addition, these sources contain a wealth of information about ancient Shinto rituals and customs, as well as the responsibilities and inviolable rights of individual families with regard to their participation in religious rites. These duties and rights expressed the special claims of certain clans to a role in the social structure of Japan, without which the clan system itself would almost inevitably collapse.

Kujiki 旧事紀 or Sendai Kuji Hongi 先代旧事本紀 ("Chronicles of Ancient Events"), Kogoshui 古語拾遺 - ("Selected Stories from Antiquity") and Engishiki 延喜式 - ("Code of the Engi Era") are also considered reliable sources. The Kujiki are believed to have been written around 620, a hundred years earlier than the Nihongi, but the oldest surviving version of the book is almost certainly not authentic. Kogoshui, written in 807, adds to the information on early Shintoism. Published in 927, the Engishiki is a fundamental source of knowledge about early Shintoism, ceremonies, prayers, rituals and methods of managing church affairs.

It should be emphasized that, unlike Christianity and Islam, none of the above manuscripts are considered sacred texts and are primarily historical records that, in addition to their political and dynastic significance, reveal ancient forms of faith.

Broadly speaking, Shintoism is more than just a religion. This is a combination of views, ideas and spiritual methods that have become an integral part of the path of the Japanese people over more than two millennia. Shinto is both a personal belief in the kami and a corresponding social way of life. Shinto was formed over many centuries by the influence of various merging ethnic and cultural traditions, both indigenous and foreign, and through it the country achieved unity under the rule of the imperial family.

In Shintoism, no canonical set of religious rules arose, since at first the temples were only ritual intermediaries between people and the kami deities, and later, when these temples began to be perceived as symbols of faith of a certain community of people, there was no need to create any doctrines and instructions.

The architecture of Shinto shrines comes in a variety of styles. Most often, it reflects a specific era or place where the temple was built, and sometimes it reflects historical periods that became milestones for the sanctuary. Many temple designs have continental influences, but there are two very ancient native Japanese styles that are considered the most typical of Shinto. The first of these was called "xinmei" 神明, which literally means "divine radiance", it is also known as tenchi kongen 天地根源, that is, "heaven descended to earth." This style is best represented in the architecture of Ise Temple 伊勢神宮. The second style is called "taisha" 大社, and is typified by the building of Izumo Temple 出雲大社.

Ancient temples were built from cypress and covered with miscanthus reeds or cypress bark. Nowadays, for fire safety purposes, church buildings in cities are erected from reinforced concrete, and roofs are made from tiles or copper sheets. It is extremely rare to see a temple made of natural stone. Various types of decoration of buildings indicate a significant influence of continental architecture.

A traditional Shinto shrine consists of two rooms - the haiden prayer hall 拝殿 and the honden room 本殿, which contains an item associated with the corresponding kami. An important part of the temple is the torii 鳥居 - a U-shaped gate that serves as a symbolic boundary between the world of people and the world of kami. Small shrines are often built on historical and legendary places, and places of worship are established near large ancient trees, which are also considered the dwellings of the kami.

In Shinto shrines, as a rule, there are no images or objects intended for worship - only symbolic objects are used for this purpose, which are kept in the shrine's sanctum sanctorum. No one is allowed to see them. Thus, compared to Buddhism and Hinduism, Shinto has relatively few works of visual art. However, Shintoism also contributed to art. Images of guardian animals have long been placed in temples, skilled artists and architects took part in the construction and decoration of sanctuaries, beautiful gardens were built around, and the wild, pristine nature near the temples was carefully protected.

Moreover, in the temples, parishioners were always encouraged to present exquisite items to the kami, which inspired artisans to demonstrate the highest skill, sometimes reaching perfection. Thus, temples played their role in preserving ancient crafts and crafts for more than a thousand years. And although it cannot be said that truly Shinto literature exists, nevertheless, many poets presented their literary masterpieces to the kami. The same goes for calligraphers, painters and sculptors. It should also be noted that temples contributed to other forms of art: thanks to them, sacred dances - kagura 神楽 ("Divine Joy"), classical music - gagaku 雅楽 (literally: "exquisite music"), and court dances - have survived to this day. bugaku 舞楽 (literally: “dance theater” or “dance and music”), drama no 能 (“skill, skill, talent”) and such a rare genre of folk art as rural drama - sato kagura 里神楽.

With the development of the imperial system, the idea of a supreme kami arose - the goddess Amaterasu 天照皇大神. Accordingly, the cult of the emperor himself arose. Myths and legends about Amaterasu and her family were officially considered the beginning of Japanese history for many years, until the mid-20th century. From the moment Buddhism arrived on the islands, the process of mutual influence and interpenetration of these religions began. There is simultaneous worship of both kami and buddhas.

During the mythological era, also called the Age of Kami, the Shinto way of daily life and worship was established. The names of the mythological gods kami and the order of their appearance differ in different written sources, for example, according to the Kojiki text, the kami of the center of heaven Amen-no-minaka-nushi-no-kami appeared first and only then the kami of birth and development Taka-mimusubi-no- Mikoto and Kami-musubi-no-mikoto. However, the actual mythology of the kami begins only with the appearance of the creative couple - Izanagi-no-mikoto and Izanami-no-mikoto. These two deities, descending from the High Heavenly Valleys, gave rise to the Eight Great Islands, that is, Japan, and all things, including many kami. Three of the kami deities were the most revered: the Sun Goddess Amaterasu-o-mikami - the kami of the Highest Heavenly Valley, her brother Susanoo-no-mikoto, who ruled the Earth, and the Moon God Tsukuyomi-no-mikoto (Tsukiyomi-no-mikoto), who was kami of the Kingdom of Darkness.

According to the Kojiki, Susanoo-no-mikoto behaved so badly and committed so many follies that the Sun Goddess flew into a rage and hid in a celestial cave, causing the heavens and earth to be plunged into darkness. Amazed by this turn of events, the celestial kami staged a dance entertainment that forced her to leave the cave; and thus the light returned to the world again. As punishment for his misdeeds, Susanoo-no-mikoto was cast into the lower world, where he regained the favor of other kami with good behavior, and his descendant, kami Izumo (Okuninushi-no-kami), became a very benevolent deity, ruling the Eight Great Islands and bringing happiness to people. Very little is said about the kami of the Moon in myth.

Subsequently, the grandson of the Sun Goddess, Ninigi-no-mikoto, received knowledge thanks to which he came to Japan and began to rule it. As symbols of power, he was given three great treasures: a mirror, a sword and a precious necklace. Moreover, he was accompanied on his journey by a kami who took part in dances in front of the heavenly cave. Nevertheless, to complete the mission, Ninigi-no-mikoto had to enter into negotiations with kami Izumo, who, after a short discussion, agreed to transfer the visible world to him, leaving the invisible world behind. At the same time, Kami Izumo made a promise to protect his heavenly grandson. Emperor Jimmu, the great grandson of Ninigi no Mikoto, became the first human ruler of Japan.

This myth, very simple in structure, explained to the ancient Japanese their origin and the basis of the country’s social structure. By analyzing it, one can trace the evolution of Japanese thought about the nature of the nation: the birth of kami and all things from chaos, the separation of things and the emergence of universal order and harmony. In a sense, this myth can be considered as the simplest constitution of the country, however, in ancient texts one can find several versions of the events described, which contradict each other, since they were formed and preserved in different clans, where they were considered in a sense the only true ones.

Modern Shintoism is a continuation of the faith that arose in the mythological era. Its rituals and cult paraphernalia today are in many ways similar to those used in ancient times. The Ise Temple 伊勢神宮 (Ise Jingu) is one of the most beautiful architectural ensembles in modern Japan - built in the style of archaic ritual buildings. Shrine Shintoism, like a flower bud that bloomed in ancient times, continues to enrich the lives of the Japanese to this day.

Shinto Gods (some of many):

Amaterasu o-mikami 天照大神—“Great Goddess Illuminating the Earth”—Goddess of the Sun. Considered the sacred ancestor of the Japanese emperors (great-great-grandmother of the first Emperor Jimmu 神武天皇) and the supreme deity of Shinto 神道. Perhaps originally revered as a male being, "Amateru Mitama" 天照御霊 - "Spirit Shining in the Sky." Myths about her are the basis of Japanese mythology, reflected in the most ancient chronicles of the 7th century - “Kojiki” 古事記 and “Nihon Shoki” 日本書紀. Its main shrine, Ise Jingu 伊勢神宮, was founded at the very beginning of the country's history in Ise 伊勢 Province. The High Priestess of the Amaterasu cult is always one of the emperor's daughters.

Susanoo-no-mikoto 須佐之男命- God of hurricanes, the Underworld, waters, agriculture and disease. His name translates to "Impetuous 荒む well done." The younger brother of the goddess Amaterasu 天照. For a quarrel with his sister and other family members, he was exiled to Earth from the Heavenly Kingdom (which is called Takamagahara 高天原) and performed many feats here, in particular, he killed the eight-headed dragon Yamato-no-Orochi 大和の大蛇, and took three symbols from its tail imperial power - Kusanagi's sword, mirror and jasper. Then, in order to reconcile with his sister, he gave her these regalia. Subsequently he began to rule the Underground Kingdom. His main shrine is located in Izumo Province 出雲.

Tsukuyomi no Mikoto 月読命 or 月読尊is the Moon God, the younger brother of the goddess Amaterasu 天照. After he killed the goddess of food and crops Uke-mochi 受持ち for disrespect, Amaterasu did not want to see him again. Therefore, the Sun and Moon never meet in the sky.

Ninigi-no-mikoto 瓊瓊杵尊is the grandson of the Japanese Sun Goddess Amaterasu, a Japanese god. Plays an important role in the key myth of the descent of the host of gods from Heaven to Earth, leading the said action at the direction of his grandmother. During his descent, Ninigi brought with him not only many gods of the Japanese pantheon, but also characters who later became the ancestors of large families that operated in historical times and each honored their “divine” ancestor. Ninigi himself became, according to legend, the ancestor of the emperors of Japan.

Izanami イザナミand Izanagi イザナギare the first people and, at the same time, the first kami. Brother and sister, husband and wife. They gave birth to everything living and existing. Amaterasu 天照, Susanoo-no-Mikoto and Tsukiyomi 月夜見 are children born from the head of the god Izanagi after the departure of the goddess Izanami to the Underworld and their quarrel. Now Izanami is revered as the Goddess of Death.

King Emma 閻魔- Sanskrit name - Yama - God of the Underworld, who decides the fate of all creatures after their death. The path to his kingdom lies either “through the mountains” or “up to the heavens.” Under his command are armies of spirits, one of whose tasks is to come for people after death.

God Raijin 雷神- God of Thunder and Lightning. Usually depicted surrounded by and beating taiko drums 太鼓. Thus he creates thunder. Sometimes he is also depicted in the form of a child or a snake. Besides thunder, Raijin is also responsible for rain.

God Fujin 風神- God of Wind. Usually depicted with a large bag in which he carries hurricanes.

God Suijin 水神- God of Water. Usually depicted as a snake, eel, kappa or water spirit. Since water is considered a feminine symbol, women have always played a major role in the veneration of Suijin.

God Tenjin 天神—God of Teaching. Originally revered as a sky god, he is now revered as the spirit of a scholar named Sugawara Michizane 管家 (845-943). Due to the fault of court intriguers, he fell out of favor and was removed from the palace. In exile, he continued to write poetry in which he asserted his innocence. After his death, his angry spirit was considered responsible for a number of misfortunes and disasters. To calm the raging kami, Sugawara was posthumously forgiven, promoted to court rank and deified. Tejin is especially revered at Dazaifu Shrine 太宰府 Tenmangu in Fukuoka Prefecture 福岡県, as well as at its own temples throughout Japan. Also called Amatsukami 天神.

God Toshigami 年神- God of the Year. In some places he is also revered as the god of the harvest and agriculture in general. Toshigami can take the form of an old man and an old woman. Toshigami prayers are offered on New Year's Eve.

God Hachiman 八幡— (literally: “Eight Banners”) - God of Military Affairs. Both the deified Emperor Ojin and the famous oracle are venerated under this name. Hachiman is especially revered at the Usa Nachimangu Shrine in Oita Prefecture 大分県, as well as at his own shrines throughout Japan.

Goddess Inari 稲荷—Goddess of Abundance, rice and cereals in general. Often worshiped in the form of a fox. Inari is especially revered at the Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine 伏見稲荷大社, as well as at his own shrines throughout Japan. Sometimes Inari is also revered in a male form, in the form of an old man.

Jizo 地蔵—Treasury of the Earth—patron of children and fear on the border with the other world. Monk with staff and gem. The Hase-dera Temple in Kamakura contains one hundred thousand small figurines in memory of deceased children.

Seven Gods of Good Luck Shichifuku-jin - 七福神- Seven Divine Beings who bring Good Luck. Their names:

- Ebisu 恵比寿- the patron saint of fishermen and merchants, the god of luck and hard work, is depicted sitting in a court costume with a fishing rod in his right hand and a fish in his left

- Daikoku 大黒- patron of peasants, god of wealth, depicted as a fat man with a wish-granting mallet and a huge sack of rice

- Jurojin 寿老人- the god of longevity, is depicted as a bald, bearded old man with an elongated head and with a shaku staff, to which a scroll of wisdom is attached, and a crane, turtle or deer, sometimes depicted drinking sake

- Fukurokujin 福禄寿- the god of longevity and wise deeds, depicted as an old Taoist with a huge pointed head with a staff and fan

- Hotei 布袋—the god of compassion and good nature, depicted as a reclining old man with a large belly, a staff and a linen begging bag

- Bishamon 毘沙門- the god of wealth and prosperity, depicted as a mighty warrior with a spear and in full samurai armor

- Benten 弁天or Benzaiten 弁財天- the goddess of luck (especially at sea), wisdom, arts, love and thirst for knowledge, depicted as a buxom naked girl with a biwa 琵琶 - the national Japanese instrument).

Sometimes they include Kishijoten 吉祥天—Bishyamon’s sister, depicted with a diamond in her left hand. They are revered both together and individually. They travel on the wonderful Treasure Ship - Takarabune 宝船, filled to the brim with all sorts of riches. Their cult is very important in the daily life of the Japanese.

The Four Heavenly Kings of the Shi-Tenno 四天王are four deities who protect the cardinal directions from the invasion of demons. They live in palaces located in the mountains at the ends of the Earth. In the east - Jikokuten 持國天or治國天("Governor of the Earth" or "Overseer of the Earth"), in the west - Komukuten 廣目天("All-Seeing"), in the south - Jochoten増長天("Grower" or "Patron of Growth") and in the north - Tamonten 多聞天("All-Hearing") or Bishamon 毘沙門- one of the seven gods of Fortune.

Dragon Lord Rinzin 龍神is the strongest and richest of all dragons, lives in a huge crystal palace at the bottom of the ocean, filled with all sorts of riches. He is the richest creature in the world. Rinzin is revered as the god of the seas and oceans under the name Umi no Kami 海の神. There are legends that Rindzin often visited the human world in human form, leaving behind many children - beautiful boys and girls with green eyes, long black hair and the ability to perform magic.

Ookuninushi 大国主 - “Great Master of the Country”, in Japan is revered as the main one over the earthly gods and is contrasted with Amaterasu - the main heavenly goddess. Although, according to state myth, Ookuninushi voluntarily ceded power on earth to the descendants of the heavenly gods, he remains the “second”, alternative main god throughout Japanese history, and at the same time changes his functions several times. This can be seen by comparing the images of Ookuninushi in different shrines. The first mystery of this god is what his name actually is, which of the names is the original, and which are substitute dignifications. Perhaps the most ancient name is Oonamochi (Oonamuti), "Possessor of the Great Name" or "...of many names." The most common name is Ookuninushi, and there is also Ookunitama, “Great Spirit of the Country”, Utsushi-kunitama, “Spirit of All Visible Lands”, Oomononushi, “Great Master of All Things” (or “... all spirits”), Ashiharasikoo no kami, "The Ugly God of the Reed Plain."

According to the mythological codes of the 8th century, Ookuninushi is a descendant of the god Susanoo, expelled from heaven to earth, and the earthly goddess Kushinada-hime, whom Susanoo saved from an eight-headed serpent: according to “Nihon Shoki” - a son, and according to “Kojiki” - a descendant in the sixth generation . Ookuninushi's birthplace is the country of Izumo on the west coast of the island of Honshu; according to other sources, other lands on the Japanese Islands or even on the Korean Peninsula. It is not entirely clear whether the same god appears every time under the name Ookuninushi in myths. For example, Ookuninushi of Izumo and Ookuninushi of Mount Oomiwa may be different deities; however, Japanese priests and interpreters of legends about the gods began to identify different Ookuninushi, Oomononushi and Ookunitama quite early. All of them are united by the function of a powerful earthly, “local” god, the marten-kami. In general, the question of the unity of the lands is the most important for the state myth, and it is resolved in two ways. Or the wild, dark earthly gods all live separately, and they are united by the descendants of the heavenly gods (Ninigi, Jimmu, Odzin, and in fact, every sovereign does this). Or, on earth, the deities are already light and inclined to order, and therefore they are drawn together, united under the authority of the supreme earthly god, and he already cedes power to the deity from heaven. None of these decisions displaces the other, which is understandable: after all, every god has a violent soul and a soft soul, the whole ritual is based on the fact that there are always two souls.

Basics of Shintoism

Shintoism is based on the concept of "kami". It is central to the entire religion, which is why Shintoism is often called the “religion of kami.” Kami is the soul, the spiritual essence of the object. The spirit of kami can be found not only in living beings or partially adjacent plants, but also in other objects and phenomena.

Kami can be good or evil. They ask the good for protection, and try to protect themselves from the evil with the help of amulets. Totemism is one of the characteristic features of Shintoism, along with multiple magical practices.

The concepts of good and evil in Japanese beliefs are very different from European ones, not having an unambiguous character. There are no universal definitions of godly actions; one should proceed from one’s own morality. The main benefit is the ability to live in harmony with oneself and the world around us.

It is important to note that initially bad does not exist. The world was a priori created ideal, and people sinless. But evil spirits bring discord both in hearts and throughout life.

The surrounding world is inhabited by spirits - kami, who, along with people, are full members of life. They embody the souls of deceased ancestors, who are always close to their descendants, watching them, evaluating their actions. A follower of Shintoism must resist demonic forces, seek protection from wise kami and not disrupt the course of life intended by nature.

Shintoists go to shrines to pray, although this is not obligatory. It is believed that a kami lives in every home - people build a small altar to this spirit and bring him offerings so that he will guard the family.

You can find altars for some kami that are not served by priests, but people take care of them themselves. For example, an altar to Inari, the patroness of the home and crafts, is often found. It can be recognized by the image of a fox, which symbolizes this goddess.

Altar of Inari

It is important to undergo a purification ritual before turning to the gods. It includes washing, changing clothes, washing hands, rinsing the mouth. A person who has recently touched something forbidden (blood, a corpse) or even seen it is not allowed to the altar.

The concepts of pure and unclean are of great importance in Shintoism; Shintoists also regularly undergo ritual cleansing from the priest - in this way their inner world is freed from filth.

Shinto shrines

Shinto shrines are places of worship and homes for the kami. Most shrines regularly celebrate festivals (Matsuris) to expose the kami to the outside world. Shinto priests perform Shinto rituals and often live on the shrine grounds. Men and women can become priests and are allowed to marry and have children. The priests are assisted by young women (Miko) during rituals and at shrines. Miko wears a white kimono, is supposed to be unmarried, and is often the daughter of a priest.

Just as Buddhism has temples, Shinto has shrines, sometimes no bigger than a wooden box with a statue in it, somewhere on the side of the road. But also great gates (Torrii) such as Fushimi Inari-Taisha in Kyoto and Meiji Shrine in central Tokyo. Here you will find altars, buildings, ponds and gardens that are in harmony to worship the Path of the Gods.

Important features of Shinto art are temple architecture and the cultivation and preservation of ancient art forms such as Noh theatre, calligraphy, and court music (gagaku), an ancient dance music that originated in the courts of Tang China (618-907).

Shinto mythology

Myths that demonstrate Shinto ideas are contained in the Nihongi and Kojiki collections. The emergence of Shintoism is described in them along with descriptions of the life of two eras. The first of them is the so-called “Era of the Gods”, then – the reign of the emperor, at which the collections end the story.

Nowhere is it mentioned how long the Age of the Gods lasted. It is only known that it began with the creation of the world and continued until the gods transferred power to their descendants - the emperors.

According to Shinto mythology, chaos preceded the creation of the world. It contained everything that exists, but in a formless, disordered form. Gradually it divided into a plain and islands. Then the gods arose and quickly created couples. From marriages, new natural objects and phenomena were born, as well as kami - their souls.

The most famous mythical divine couple are the gods Izanagi and Izanami. It was from their union that the islands, later inhabited by people, arose. From them other gods appeared. The emergence of people is not discussed separately in Shinto myths. The Japanese do not see much difference between living people and kami; their existence has always been parallel. From myths come the origins of many rituals that are strictly observed to this day.

The myth of Susanoo laid the foundation for the rituals of sacrifice. Susanoo, the god of wind, once seriously offended his sister Amaterasu with unworthy behavior. To earn forgiveness, he brought her gifts of thousands of tables with the most exquisite dishes.

Since then, setting a rich table for the mercy of the gods has been one of the traditions. Sacrificial food should belong to different categories, be both prepared and donated by living beings (caviar, eggs). The Japanese even bury treats in the ground, believing that the kami treat them there, or display them in front of temples. Spirits live everywhere, and food is offered to them everywhere too.

Later myths tell of the struggle between gods and kami for power over territories. From there we learn about the god Ninigi, who was the first to descend to earth to rule people. It was from him that the line of emperors descended. Some legends contain information about five more gods ruling the earth, who laid the foundation for other imperial clans.

Relationships with other religions

Shintoism does not intend to contradict other beliefs and never speaks of their falsity. In its depths, manifestations of many religious teachings exist freely.

Shintoism and Buddhism

Japan is characterized by religious syncretism (the phenomenon in which people profess several religions at once). Therefore, along with Shintoism, the overwhelming number of Japanese also profess Buddhism. This is manifested in the observance of the rituals of two religions at the same time. The vast majority of Japanese celebrate traditional Shinto weddings, and funerals are carried out according to the requirements of Buddhist teachings.

Buddhism, which came to Japan from neighboring China, introduced its own features and itself borrowed some norms from Shintoism. He turned his attention away from the cult of dead ancestors, switching it to more pragmatic things. Along with Buddhism came ideas about statehood and social order.

Considering that the origins of Shintoism in its current form largely come from Buddhism, the two religions have many similarities.

- religions are united by the theme “The Path”. In the first case, this is the path of the Buddha, in the second, the path of the kami;

- the presence of a temple and priests, similar stylistic design of prayer places;

- common gods and rituals that migrated from one religion to another as a result of confusion.

But the two religions still have differences:

- Shintoism has no founder and, moreover, it is impossible to reliably calculate even the age of its appearance. While the era of Buddhism begins with the enlightenment of Buddha;

- Buddhism does not accept the cult of the souls of deceased ancestors;

- Despite the recognition of some Shinto gods, veneration does not extend to inanimate objects sacred to Shinto.

There were many attempts to prevent the mixing of Shintoism and Buddhism - syncretism did not suit one side or the other. But assimilation still happened. Now it is no longer possible for people professing both religions to choose in favor of only one of them.

Shintoism and Christianity

At first glance, these two religions have nothing in common. They cannot be combined into any one category. What they have in common is only a massive following. Although Christianity wins in this regard, especially since it is characterized by different forms and community for many people on different continents.

Shintoism also has several movements, but they are concentrated mainly in one country. It is also not monotheistic - there is no creator and founder of religion. In addition, Shintoism involves imparting spirituality to inanimate objects, which Christianity considers a terrible sin.

But still some common features can be identified. First of all, both religions talk about the soul and consider it important to take care of it. Modesty, the desire not to judge others, to be generous and selfless are also encouraged. Ritual cleansings take place in temples, which have common features. Similar symbolism is characteristic of many religions.

As for the attitude of Shintoists towards Christianity, it has always been wary. The need to serve only one god from the point of view of monotheists seems to be a betrayal of all other gods. Since Shintoism is more than a religion (it is a worldview, part of a culture), Christianity did not take root on Japanese soil.

Shinto then and now

Shinto, "The Way of the Gods"

Several conflicts followed with the advent of Buddhism in the 6th century, but the two religions were soon able to coexist and even complement each other. Many Buddhists viewed kami as manifestations of the Buddha.

In addition to this practice, Shinto also developed as an organized religion; between 1868 and 1945 it was the state religion. Shinto priests became government officials, important shrines received government funding, Japan's creation myths were used to reinforce a national identity with the Emperor at its center, and efforts were made to separate and liberate Shinto from Buddhism. After World War II, Shinto and the state were separated.

People seek support from Shinto by praying at home altars or visiting shrines. A range of talismans are available at shrines for traffic safety, good health, business success, safe childbirth, good exam results, as guidance which means a lot in martial arts, and much more.

A large number of wedding ceremonies are held in the Shinto style. Death, however, is considered a source of impurity and is left to Buddhism. Consequently, there are virtually no Shinto cemeteries, and most funerals are conducted in the Buddhist style.

Confucianism

There are seven different types of Shinto shrines, namely imperial shrines, Inari shrines, Hachiman shrines, Tenjini shrines, Sengen shrines, and local shrines.

Purification pool next to a Shinto shrine.

What does a typical Shinto shrine ?

- Torris - Red gate that usually stands at the entrance or passageway to a Shinto shrine

- Komainu - A pair of guard dogs or lions guarding the entrance.

- Washing area - Before you can enter the temple, you must first rinse your hands and mouth.

- The main hall for offerings - "Sopaki", also called the main hall, and "Hayden" for offerings offer a price in the center of the temple.

- Ema - Visitors write their wishes here on wooden boards in the hope that they will come true. Usually it is about achieving success or the health of others

- Omikuji - Omikuji are future-predicting documents that can be drawn at random. They usually predict part of your future.

- Shimenawa is a rope with zigzag paper strips that represent a shrine. You'll usually find them near the entrances in the Torris area or on old trees or altars in towns.

Shinto shrines.

Views: 4,484

Share link:

- Tweet

- Share posts on Tumblr

- Telegram

- More

- by email

- Seal

Modern Shintoism

Currently, Shinto continues to play a vital role in the spiritual life of Japan. There are tens of thousands of temples across the country, and two universities train Shinto clergy. Traditional rituals are regularly performed in churches, and religious holidays are widely celebrated.

But traditions are observed not only in temples. Shinto rituals have become firmly established in the life of modern Japanese, and he follows them. It is noteworthy that even that part of the people who do not consider themselves Shintoists cannot avoid not performing traditional rituals: cleansing the house, completing transactions with a loud clap in the palm, etc.

Despite the high development of the Land of the Rising Sun, more than 90% formally fulfill all the requirements of Shintoism. This is largely due to the fact that Shintoism does not interfere with the development of high technology and does not put forward any prohibitions on social life. This religion is a purely individual faith that addresses the personal moral component of a person.

Moreover, even denying your religiosity, it is impossible to deny culture and not fulfill those cultural requirements that were absorbed from childhood. That is why only a person brought up in a characteristic environment can be a true Shintoist.

Kami ranks

In the past, some of the kami had ranks similar to those operating at the imperial court. These ranks were assigned by the emperor himself and largely influenced the rank of the corresponding kami of the jinja sanctuary. If officials had 13 “bun” ranks, then the kami had 15. The number of “kun” and “hin” ranks for people and kami coincided - 12 and 4, respectively. In this case, there was an attempt to transfer to Japan the Chinese religious model, in which the internal organization of the gods repeated the state organization. However, the bureaucratization of the kami failed, and they never became full-fledged counterparts to government officials[5].