In the Japanese language there are many particles with the help of which the descendants of samurai express emotions (delight, agreement, surprise, exclamation, etc.). However, it must be taken into account that these particles are used exclusively in simple speech. If you need to translate text into or from Japanese, and you doubt your capabilities, it is better to seek help from the Prima Vista bureau by following the link www.primavista.ru/rus/perevod/japanese.

Cases in Japanese - 10 cases in Japanese

This is a must-have topic for learning Japanese.

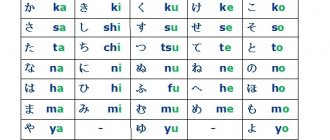

| Latin | Hiragana | Case | Question | |

| 1 | Ga | が | Nominative (rhematic) | Who what? |

| 2 | No | の | Genitive | Whose? Which? |

| 3 | Wo | を | Accusative | Who/what? |

| 4 | Ni | に | Dative | To whom; to what? From whom/what? Where? (with verbs of being) Where? When? |

| 5 | De | で | Instrumental | By whom/what? Where? (with active verbs) Of what? (with materials) |

| 6 | To | と | Joint | With whom/what? |

| 7 | E | へ | Case of direction | Where? |

| 8 | Kara | から | Original | Where? From what time? |

| 9 | Made | まで | Limit | To where? Until what time? |

| 10 | Yori | より | Initial-comparative | Regarding what? From whom? |

We will also consider a number of particles that are not cases, but often take on their function:

Wa (は) is an emphatic thematic particle.

Mo (も) is a particle meaning “also, also.”

Piece of context - 「で」

A context particle is used to describe the context in which or through which the action of a verb occurs. For example, if you are eating in a restaurant, since restaurant is not the direct target of the verb "to eat", you would not use the particle 「に」. Instead, you'll use the particle 「で」 to show that the restaurant is the context in which food consumption occurs.

Example

- レストラン - restaurant

- 日本語【に・ほん・ご】 - Japanese

- 話す【はな・す】 - to speak

- はし - chopsticks

- Cinema

- 仕事【し・ごと】 - work

- 忙しい【いそが・しい】 (and adj.) - busy

- レストランで食べる。Available in the restaurant.

- 日本語で話す。Speak Japanese. (Speak using Japanese.)

- はしで食べる。Eat with chopsticks. (Eat with chopsticks.)

- 映画館で映画を見る。Watch a movie in the cinema.

- 仕事で忙しい。Busy with work.

Cases in Japanese - Genitive NO (の)

➀ Answers whose question? Which? Marks affiliation.

Watashi no kutsu

My shoes

Gakusei no pen

Student pen

Note that in Japanese the definition always comes before the word being defined.

➁ In addition, の can be used in cases where we are talking about the content of an information medium, such as a book, textbook, dictionary, magazine, cassette, disk, etc.:

Nihongo no jisho

Japanese Dictionary

➂ There is also a use that is completely uncharacteristic for the Russian language - an explanation of who the person we are talking about is:

友だちの田中さん Tomodachi no Tanaka-san

Friend Tanaka (= Tanaka who is a friend)

Complement particle - 「を」

The particle 「を」 is used to directly indicate the object to which the action is directed.

Note

: Although technically 「を」 is the sound of the 「わ」-series, it is pronounced the same as 「お」.

Example

- 映画 【えい・が】 - movie

- 見る【み・る】 - to see; look

- ご飯【ご・はん】 - rice; food

- 食べる【た・べる】 - eat (consume food)

- 本【ほん】 - book

- 読む 【よ・む】 - read

- 手【て】 - hand

- 紙【かみ】 - paper

- 手紙 【て・がみ】 - letter

- 書く【か・く】 - write

- 映画を見る。Watch a movie.

- ご飯を食べる。There is rice/food.

- 本を読む。Read a book.

- 手紙を書く。Write a letter.

Accusative case WO (を)

➀ Answers the question “who/what?” and is used with transitive verbs, for example:

テレビを見る。Terebi wo miru.

Watch TV.

➁ Also, the accusative case suffix WO (を) is used with some intransitive verbs that denote movement on a surface, for example:

公園を散歩する。Kouen wo sampo suru.

Walk in the park.

空を飛ぶ。Sora wo tobu.

Fly across the sky.

➂ And finally, WO (を) is used when we leave somewhere:

部屋を出る。Heya wo deru.

Escape from.

Dative case NI (に)

This is perhaps the richest Japanese case in its use.

➀ Answers the question “to whom/what?”

猫にやりました。Neko ni yarimashita.

Gave it to the cat.

➁ Answers the question “from whom/from what?”

Tomodachi ni moraimashita.

Got it from a friend.

➂ Answers the question “where?” and is used with such verbs of being as the verbs imasu (います, to be), arimasu (あります, to be about inanimate objects) and sunde imasu (すんでいます, to reside):

犬は家にいます。Inu wa ie ni imasu.

The dog is in the house.

➃ Answers the question “where?” and is used with verbs of motion such as ikimasu (いきます, to go, go, leave, leave), kimasu (きます, to come, to come), kaerimasu (かえります, to return to one’s home), modorimasu (もどります, return), etc.:

アメリカに帰った。Amerika ni kaetta.

Returned to America.

➄ Answers the question “when?” and is used with those time indicators that have a number, as well as with days of the week:

8時に始まります。Hachiji ni hajimarimasu.

Starts at 8 o'clock.

Target particle - 「に」

The target particle is used to indicate the purpose of an action, whether it is time or place. It serves as an analogue of “in”, “on”, etc. as long as it denotes the goal of the action.

Example

- 【がっ・こう】 – school

- 行く【い・く】 - go

- 明日 【あした】 - tomorrow

- くる - to come

- バス - bus

- 乗る【の・る】 - to go

- 聞く【き・く】 - to ask; listen

- 前【まえ】 - before

- 立つ【た・つ】 - stand

- 友達【とも・だち】 - friend

- 会う【あ・う】 - to meet

- 学校に行く。Go to school.

- 親戚は、明日にくる。Relative(s), will come tomorrow.

- バスに乗る。Go by bus.

- 先生に聞く。Ask/listen to the teacher.

- 人の前に立つ。Stand in front of people.

- 友達に会う。Meet a friend.

Instrumental case DE (で)

➀ The instrumental case DE (で) answers the question “by whom/what” and marks the instrument of action, for example:

日本人は魚を箸で食べる。Nihonjin wa sakana wo hashi de taberu.

The Japanese eat fish with chopsticks.

➁ Also, the instrumental case DE (で) answers the question “where” and marks the space in which the action is performed. Used with active verbs (i.e. almost all verbs except imasu (います), arimasu (あります) and sunde imasu (すんでいます)).

教室で勉強します。Kyoushitsu de benkyou shimasu.

I study in the classroom.

➂ Another interesting function of the instrumental case DE (で) is its use with quantity. For example, it can be used with a number of people, indicating "how many" an action was performed (two people, alone, etc.):

二人で行きました。Futari de ikimashita.

Let's go together.

Or, for example, how much money the product was purchased for:

300円で買った。Sambyakuen de katta.

Bought it for 300 yen.

➃ In addition, the instrumental case DE (で) will indicate the material from which the object is made, in the event that this original material is visible to the naked eye:

Kono isu wa afurika no ki de tsukurareta.

This chair was made from African wood.

In case the raw material is changed so much that we no longer see it. For example, we know that sake is made from rice, but it is a clear liquid with no rice inside - then we will use the original case KARA (から), which will be presented below.

Direction case E (へ)

➀ Answers the question “where” and is used with verbs of motion:

図書館へ行く。Toshokan e iku.

Go to the library.

In this function it practically coincides with the accusative case NI (に). And although they are interchangeable in almost all cases, the NI (に) case is more likely to indicate the final destination of arrival, while when we put the E (へ) case, the emphasis is more on the path to that place. In other words, in the example above, we could go out in the direction of the library, but whether we get there or sit down on the way to eat ice cream and admire the birds is another question!

Cases in Japanese for comparison

Original comparative case YORI (より)

➀ Answers the question “relative to what?”, “in comparison with what?”.

The suffix of the original comparative case YORI (より) is used to construct comparative constructions for adjectives. The fact is that Japanese adjectives do not have a comparative degree. We can say "big" - ookii (おおきい), but the word "bigger" simply does not exist in Japanese. But we still need to compare, otherwise how will we know whose grass is greener and whose sky is bluer. Therefore, in Japanese we can indicate in relation to what an object is large. For this we will use the suffix of the original comparative case YORI (より):

Tokyo wa Osaka yori ookii desu.

Tokyo is bigger than Osaka. (=Tokyo is big compared to Osaka).

➁ In addition, it has one more function - actually, originality. In this it is similar to the KARA (から) case. This is a rather archaic usage and is currently used, perhaps, only in letters:

Yamada yori

From Yamada

★★★

The question of correct placement of cases depends entirely on the verb and those constructions that are at the end of the sentence. It is important to understand that nouns themselves do not need cases, in other words, while a chair is just a chair existing in space, it does not need cases. Cases will appear when we see this chair, sit on it, go to it, etc., that is, this or that control will appear. In this regard, it is very important to pay attention to which cases a particular verb is combined with and remember verbs either with a case, or even in conjunction with a noun. For example, the verb AIMASU (会います), "to meet" will be ruled either dative NI (に) or collateral TO (と):

友達と会った。 Tomodachi to atta.

Met a friend.

熊に会った。Kuma ni atta.

Encountered a bear

Cases in Japanese are the basis for forming sentences, so you need to master this topic to communicate competently.

Case markers は “wa” and が “ga” in the context of classroom translation practice

As practice shows, students studying Japanese are introduced to “wa”, as a rule, in their first Japanese grammar lesson. In the textbook they read: 私は学生です。Watakushi wa gakusei des. I am a student. This phrase forms the cornerstone of the “building” called “Japanese Grammar,” which students will now build together with the teacher. Students read the sentences: あの方は先生です。Anokata wa sensei des. That person is a teacher. これはいすです。.Kore wa isu des. This is a chair. あの人はだれですか。Anohito wa dare des ka. He who? Etc.

Having begun their acquaintance with the case indicator “va” with such sentences, students conclude that the word with “va” is the subject of the sentence. And few people pay attention to the explanations in the textbook and the teacher’s words that “va” “emphasizes subject as the topic of the statement”, that “the subject with “va” contains already known old information, and new information in such sentences is contained in the predicate”, etc. At this stage, students tend to equate the word with “va” and the subject of the sentence. Therefore, the feelings of surprise and confusion that arise among students when the topic “indicator of the nominative case “ha”” appears in the next lesson is understandable.

“Why do we need another nominative case if we already have “va”?” – the students are perplexed. And this bewilderment is understandable. After all, the teacher, explaining this or that topic of Japanese grammar, draws parallels with the native language, i.e. in Russian. (As practice shows, this approach makes it easier for students to understand and remember the material.) In the native Russian language, there is only one nominative case. And, if in Japanese the nominative case is “ga”, then what is “wa”? What is its role and function in the sentence? Indeed, in the Russian language there is no case similar to the Japanese “wa”. And this circumstance creates certain difficulties in learning.

Let's look at the terminology first. In Japanese linguistic literature, “wa” and “ga” are called 助詞 (joshi) or 格助詞 (kakujoshi), which are translated into Russian as “function words”, as well as “particles” or “case particles”. In the domestic linguistic literature, each researcher offers his own name, such as “case postpositions”, “word morphemes”, etc. Russian teachers often use the word “case indicators” when working with students. There are many case indicators in Japanese. Here we consider only two of them: “ga” and “va”. In Russian, が "ha" is called the "nominative case". And は “va” has several names: “thematic nominative case”, “distinctive case”, “distinctive particle”, etc. There is nothing like this, as we know, in the native Russian language.

Let's look at different uses of "va". And then we turn to the use of the nominative case “ga”.

The fact that “va” has many names is explained by the different functions that “va” performs in a sentence.

Firstly, “va” is the subject case. 田中さんは技師です。Tanaka san wa gishi des. Tanaka is an engineer. In this function it coincides with "ha" as a nominative case. However, mechanically replacing it with “ga” in the above example will entail the need to shift the emphasis when translating into Russian, changing the logical stress. We will talk about this in detail below.

Secondly, “va” is the so-called “thematic” or “logical” subject in a sentence where there is a “grammatical” subject. For example: 東京は人口が多い。To:kyo:wa jinko:ga oi. Tokyo has a large population. 象は鼻が長い。Zou: wa hana ga nagai. An elephant has a long trunk (literal nose).

Thirdly, “wa” is an excretory particle that can stand with secondary members of a sentence, such as an object, circumstances, etc. For example: 本は読みません。Hon wa yomimasen. Doesn't read books. 日曜日には行きます。Nichiyo:bi ni wa ikimas. I'll go on Sunday.

And fourthly, “wa” is a morpheme in verbal and adjectival forms.-ではありません。de wa arimasen. no, -is not (someone, something); してはなりません。-site wa narimasen. you can't (do something); しはします。-si wa simas. I do something I do. Etc.

Let's look at different uses of "va".

In the previously given example: 私は学生です (Watakushi wa gakusei des. I am a student.) the particle “wa” functions as a nominative case, and the member of the sentence followed by “wa” is also the subject in translation into Russian. However, this is not always the case.

Take, for example, sentences such as: 今は日本語の授業です。Ima wa nihongo no jugyo: des. Now it's a Japanese lesson. ここは教室です。. Koko wa kyo:shitsu des. There's an audience here. In these sentences, the words 今 ima now and ここ koko here, followed by “wa,” are translated into Russian by the circumstances of time and place, respectively.

Let us now turn to the role of “va” as a thematic particle or, in other words, the thematic case. In this role, “va” follows an isolated thematic subject, which, in turn, is so called because it is associated not with a specific predicate, but with the entire sentence as a whole. For example: 教科書はネチャエワ先生の教科書を使います。 Kyo:kasho wa Netyaeva sensei no kyo:kasho o tsukaimas. We use the textbook by Nechaeva L.T. (As for the textbook, we use the textbook by L. T. Nechaeva)

Students of Japanese tend to translate such sentences with a separate thematic subject, starting with the words “as regards” or “if we talk about such and such”, etc. Without even suspecting it, they go back to the etymology of the particle は “wa”, the origin of which Japanese grammarians themselves associate with the conditional form ば “ba” - if. As you can see, both are written with the same letter of the Japanese alphabet.

Students will learn that in Japanese sentences, in addition to the grammatical subject, there is a so-called “logical” subject. This is a specially highlighted word that represents the topic of the statement. When we translate such a sentence into Russian, the logical or thematic subject, designated by the word with “va,” turns into other members of the sentence: circumstances of place, time, etc. (See example sentences above and below.)

As students further learn the language, they often encounter sentences with a thematic subject with “va.” Let's give a few simple examples.

この野菜は葉を食べます。 Kono yasai wa ha o tabemas. The leaves of these vegetables are eaten. (As for these vegetables, the leaves are eaten.)

会場は裏の地図をご覧ください。 Kaijo: wa ura no chizu o goran kudasai. The location of the event is indicated on the map on the back. (For location, see map overleaf.)

私はコーヒーだ。 Watashi wa ko:hi: yes. I'd like some coffee. (Literally: I am coffee.)

Kare wa kondo mo ko:hi: dake de atta. And this time he only drank coffee. (And this time it's only coffee.)

I remember the case of Russian students during an internship at a Japanese university. On a Tokyo subway train, there was a poster advertising the famous department store "Isetan" with the inscription: 贈り物は伊勢丹へ。Okurimono wa isetan e. One of the students expressed admiration for the “capacity” of the Japanese language, which allows, in such a condensed form, as she put it, to convey an idea that sounds quite lengthy in Russian. Namely: “If you need to choose a gift, we recommend visiting the Isetan store.” To which her colleague, quickly getting her bearings, offered the same “compact”, like the original, version in Russian: “For a gift, go to Isetan!”

But let’s go back to the first year, when the student, getting acquainted with common sentences of the Japanese language, including minor members, such as complements and adverbials, encounters another function of “wa” - excretory. 今度の日曜日には上野へ行きます。Kondo no nichiyo:bi ni wa ueno e ikimas. Next Sunday I will go to Ueno. The excretory particle “va” follows additions and circumstances (in this particular example, the adverbial time), highlighting and strengthening them, as is clear from its name. In some cases, it comes after the case indicator, and in some cases, at the will of the author, it can displace the case indicator of the noun. The accusative case indicator を “o” is always replaced by the particle “va”. It must be said that students, trying to imitate the use of “va” that they see in the texts they study, at first experience confusion, and then begin to put “va” where they should and shouldn’t. especially true for the circumstances of place and time . neither va, de va when? Where? The student himself cannot explain why he put “va”. To give a sense of the meaning of “va” as an excretory particle, it is necessary to give many examples of sentences, including pairs of sentences that differ only in the presence or absence of “va”.

東京にありません。—東京にはありません。To:kyo:ni arimasen. Not in Tokyo. (Neutral). To:kyo: ni wa arimasen. But not in Tokyo. (Keeping in mind that somewhere in other cities, for example: in Osaka or Nagoya, maybe there is. But specifically in Tokyo, not.)

Hiru gohan o tabemas. I'm eating lunch. (Neutral). Hiru gohan wa tabemas. I'm eating lunch. (Keeping in mind that I (maybe) skip breakfast, I can’t say about dinner. But specifically, as for lunch, I eat lunch.)

あなたには言いません。Anata ni wa iimasen. I won't tell you. (I might tell someone, but not you.)

東京からは遠い。To:kyo:kara wa tooi. Far from Tokyo. (I’m not talking about other cities. But it’s far from Tokyo specifically.)

君とはけんかしない。Kimi to wa kenka shinai. I won’t quarrel with you (specifically, with you).

東京には住みたくない。To:kyo:ni wa sumitakunai. Where, where, but I don’t want to live in Tokyo.

京都へはいつお出かけですか。Kyo:to e wa itsu odekake des ka. When are you going to Kyoto? (I know that you travel to different cities. But now I’m only interested in Kyoto.)

The teacher himself can give many similar examples until the meaning of “va” as an excretory particle becomes clear to students.

To check their mastery of the material, you can ask students to independently explain what the difference is between several sentences with the same meaning and with the particle “va” with different minor members. For example, the sentence: “Yesterday I did not go to Kobe.”

1.私は昨日神戸へ行かなかった。2.私は昨日は神戸へ行かなかった。3.私は昨日神戸へは行かなかった。First: Watashi wa kino: ko:be e ikanakatta. Yesterday I did not go to Kobe. (Neutral). Second: Watashi wa kino: wa ko:be e ikanakatta. Denies "yesterday". Those. I went on other days, but not yesterday. Third: Watashi wa kino: ko:be e wa ikanakatta. Denies Kobe. Those. Yesterday I went to other cities, but didn’t get to Kobe.

And finally, the function “wa” in various verbal and adjectival forms, starting with a simple negation - ではありません, usually does not present difficulties, but requires simple memorization. 学生ではありません。Gakusei de wa arimasen. Not a student.

Later in the grammar course, students become familiar with various grammatical constructions that contain “wa”, for example: 読みは読んだ. Yomi wa yonda. I read something. And many others.

Students are advised to memorize such grammatical constructions in their entirety after the teacher explains what parts they consist of.

Let us now turn to the nominative case が ga. A beginner learning Japanese usually becomes familiar with it after “wa”. The teacher explains that the subject of a sentence is in the nominative case “ha” when logical stress falls on it, and the information conveyed by the subject is new. Phrase: “アンナさんが学生です。Anna san ga gakusei des.” Anna is a student." — is the answer to the question: “だれが学生ですか。Dare ga gakusei des ka. Who is the student?

Sentences with "ga" answer the questions: Who or what is someone or something? Who is doing something? What has such and such properties? Etc.

Question words as subjects are in the nominative case “ga”. だれがしますか。Dare ga shimas ka. Who will do it? 何がありますか。Nani ga arimas ka. What is (is available)? どの本があなたのですか。Dono hon ga anata no des ka. Which book is yours?

Accordingly, in answers to such questions, the subject is also formalized with the “ha” case. Provided that the same word order is preserved as in the question, i.e. the subject and predicate do not change places. For example: どなたが山田さんですか。―私が山田です。Donata ga Yamada san des ka. Who is Yamada? -Watashi ga Yamada des. I am Yamada.

Dore ga kyo :kasho des ka . Where (which subject) is the textbook? - Sore ga kyo: kasho des. Here's the tutorial.

Students memorize some typical sentences and grammatical constructions with a topic word with “va” and a grammatical subject with “ga.” Like, for example: 冬は夜がながい。Fuyu wa yoru ga nagai. In winter the nights are long. 私のねこは目が青いです。Watashi no neko wa me ga aoi des. My cat has blue eyes. 日本語の教室は天井が高いです。Nihongo no kyo:shitsu wa tenjo: ga takai des. The Japanese language auditorium has high ceilings.

Such sentences begin with a word with “va”, which is usually called the thematic subject, because it “states” the topic of the sentence, where there is a proper subject in the nominative case with “ga”.

To make the translation of the sentence 冬は夜がながい。Fuyu wa yoru ga nagai different from the translation of the sentence 冬の夜がながい。Fuyu no yoru ga nagai, it is recommended to translate the first sentence (with the thematic subject with “wa”) starting with the word with “wa”, highlighting it, as the Japanese author wants, namely: “The nights are long in winter.” Not “Long Winter Nights.” And further: “My cat has blue eyes,” and not “My cat’s eyes are blue,” etc.

Let's give an example when, within the same sentence, moving “va” and “ga” changes the logical meaning of the statement. 1. 太郎は頭が悪い。Taro: wa atama ga warui. Tarop thinks poorly. (The sentence characterizes the qualities of a person named Taro.) 2.太郎が頭が悪い。Taro: ga atama ga warui. Tarot doesn't think well. (The sentence answers the question: Who doesn’t think well?) 3.頭は太郎が悪い。Atama wa Taro: ga warui. But Tarot doesn’t think well. (The topic of the sentence is mental abilities. As for mental abilities, we can cite the example of the Tarot, which is not doing well.)

Students should remember that some Japanese words, such as 好き、きらい、上手、下手、ほしい、分かる、できる and others that students learn, control the word in the nominative case "ga". 私は果物が好きです。Watashi wa kudamono ga ski des. I like fruits. 友達は料理が上手です。Tomodachi wa ryo:ri ga jo:zu des go. My friend is a good cook. 車がほしい。Kuruma ga hoshii. I want a car. 日本語が分かる。Nihongo ga wakaru. Understand Japanese. スケートができる。Suke:to ga dekiru. Know how to skate.

In the future, students will learn grammatical constructions that contain “ga”. For example: する事ができる。-suru koto ga dekiru.-can do. したことがある。-shita koto ga aru. - happened to do. Etc.

Let us turn to the question of choosing “va” or “ha” with the subject. Let’s make a reservation at the beginning that the Japanese themselves do not see this as a problem, and their inner instinct tells them when to put “wa” and when to “ga”. However, Japanese linguists, describing the phenomena of Japanese grammar, began to explore the topic of 「"は"と"が"の使い分け 」Wa to ga no tsukaiwake back at the beginning of the 20th century. When to use “va” and when to use “ga”. Research in this area continues to this day. Each Japanese grammarian offers his own vision of the problem, as well as his own approaches and criteria for choosing “wa” or “ga”. Nevertheless, several general indisputable provisions can be identified regarding when to put “va” and when to put “ha” with the subject.

Firstly, this is the principle of “new and old”. When new information is contained in the subject, a “ga” is placed after it. If the subject is something that we knew about before, then it is “va”. Here it is appropriate to compare the cases “ha” and “va” with the English articles “a(an)” and “the”, respectively. A typical example is fairy tales, when in the very first sentence the subject is with “ga”, and in the next sentence the same subject is with “ wa ” . 👍 Mukashi mukashi aru tokoro ni oji :san to oba:san ga sunde imashita. Oji:san wa itsu mo yama e shibakari ni ikimashita. Oba: san wa kawa e sentaku ni ikimashita. Once upon a time there lived an old man and an old woman. The old man went into the forest to chop wood, and the old woman went to the river to wash clothes.

Sentences with a subject with “va” contain a judgment, the speaker’s conclusions about an event or situation. Whereas a sentence with a subject with “ga” describes what is happening, records an event or situation. For example: バスが来た。Basu ga kita. The bus has arrived. 雨が止んだ。Ame ga yanda. The rain has stopped. 風が吹いている。Kaze ga fuite iru. The wind blows.

The listed sentences with a subject with “ha” reflect a specific event. Let's compare a few more sentences: 雨が降っている。Ame ga futte iru. It's raining. 雨は水滴だ。Ame wa suiteki da. Rain is drops of water. In the first phrase with "ha" the speaker reports what he saw. The second phrase with “va” carries a conclusion. However, the following sentence is also possible: 雨は降っている。Ame wa futte iru. It is raining. This phrase was born as a result of the speaker wondering: “What's with the rain? Maybe he wasn't there? Or did it exist, but ended? But no, it turns out it’s coming. It is raining. Thus, this contains the conclusion that the speaker draws after assessing the situation.

After “va” you can always pause in speech. And after “ga” you can’t. Some statements, especially interrogative ones, end with “va”. For example: これは梅の木です。Kore wa ume no ki des. This is a (tree) plum.― じゃ、それは?Jia, sore wa? And this? -それは桃の木です。Sore wa momo no ki des. it a peach ? What about that? ―あれは桜の木です。Are wa sakura no ki des. And then Sakura.

Precisely because a sentence with “wa” is perceived as a conclusion made after deliberation, as a result of reflection, in Japanese proverbs and in idiomatic expressions the subject usually comes with “wa”. 花は桜、人は武士。Hana wa sakura,hito wa bushi. Real flowers - sakura; real man - samurai. 男は度胸、女は愛嬌。Otoko wa dokyo:,onna wa aikyo:. The main thing in a man is courage, in a woman - charm.

Now it becomes clear why in negative sentences the subject is with “va”. After all, before we deny something, we must think and make a judgment. 私は学生ではありません。Watashi wa gakusei de wa arimasen. I am not a student. — It is impossible to replace “va” with “ga” in this case. The phrase 私が学生ではありません Watashi ga gakusei de wa arimasen does not exist in Japanese.

And finally, it follows about “va” extends to the entire sentence to the end. Whereas the “strength” of “ga” is only enough to reach the nearest verb or predicate. Therefore, there is a rule that in complex sentences the subject of the main sentence comes with “va”, and the subject of the subordinate clause with “ga”. For example: 私たちは彼が買った本を読んだ。Watashitachi wa kare ga katta hon o yonda. We read the book he bought. 私はアンナさんが来ないと思う。Watashi wa Anna san ga konai to omou. I think Anna won't come.

Let us give a few examples to illustrate how far the influence of “va” and “ha” extends in a sentence.

鳥が飛ぶときには空気が動く。Tori ga tobu toki ni wa ku:ki ga ugoku. When birds fly, the air trembles. 鳥は飛ぶときに羽根をこんな風にする。Tori wa tobu toki ni hane o konna fu: ni suru. Birds make these movements with their wings when they fly.

The next two pairs of sentences differ only in “va” and “ga”. 彼はコートを脱ぐとハンガーにかけた。Kare wa ko:to o nugu to hanga: no kaketa. 彼がコートを脱ぐとハンガーにかけた。In the first sentence, “the man, having taken off his coat, hung it on the hanger himself,” which follows from “va” with the subject. As for the second sentence, “he took off his coat,” but it’s hard to say who hung the coat on the hanger. Because the subject “he” is framed in the case “ha”.

花が咲く時にはいい匂いがする。Hana ga saku toki ni wa ii nioi ga suru. When flowers bloom, there is a fragrance. 花は咲く時にはいい匂いがする。Hana wa saku toki ni wa ii nioi ga suru. Flowers release a scent when they bloom.

In conclusion, we can say that by drawing students’ attention to “va” and “ga” in a sentence each time, the teacher teaches them to understand the deeper meaning of the text, and not just mechanically translate words. Teaches you to catch the intonations and accents that the author makes using “va” and “ga”. Otherwise, the student’s ignoring the difference between “va” and “ga” can lead to serious translation distortions when the logical connection of the narrative is lost. This happens especially noticeably in senior years, when students deal with complex texts and, although correctly translating words and understanding grammar, nevertheless cannot convey the author’s thought, the key to which is often hidden behind “va” and “ga.”

Literature:

- Konrad N.I. Japanese language syntax. L., 1937.

- Lavrentyev B.P. Practical grammar of the Japanese language. M., 1998.

- Masuichi Kieda. Grammar of the Japanese language. M., 1958.

- Nechaeva L.T. Japanese for beginners. M., 2006.

- 松下大三郎.「改撰標準日本語文法」紀元社, 1974.

- 1985.

- 1996.