Japan 19th century - our time. The history of the creation of the Japanese Empire.

In the second half of the 18th century, ships from Russia, England, the USA and France began to periodically appear in the waters near the Japanese archipelago, which competed for control over the Asian colonies.

The Japanese government continued its course of isolation and rejected the creation of diplomatic ties with these states. In 1825, the government issued decrees whose purpose was to strengthen maritime security, but could not resist foreign influence for long.

The beginning of a new era

Japan began to change in the early 19th century under the gradually increasing influence of Western powers. At the beginning of the 17th century, the government decided to limit international contacts and ban Christianity in order to preserve the internal integrity and culture of the country. These prohibitions remained in place in the first half of the 19th century, but the situation on the world stage was changing, and Japan had to adapt to new realities.

In the Land of the Rising Sun, at the beginning of the 19th century, economic growth was noted due to the development of manufactories. In the first years of the century, 90 manufactories operated, by the middle of the third decade there were almost 400. Development affected all areas of industry, the production of copper, iron, and gold mining. The period was accompanied by the formation of a progressive layer of the industrial bourgeoisie. The transition from a feudal social system to a bourgeois one was prepared by the cultural policy of recent centuries - by the beginning of the century, the level of education among the population was one of the highest in the world.

The Japanese attitude towards education is a special issue. In Japan there were samurai public and schools for the common population. Listeners were taught to write, read, count; explained the principles of Confucianism. The state encouraged a progressive educational system; Japanese studies and Dutch studies were taught in many institutions. An important element of the educational policy of the era is kokugaku, a principle laid down by Motoori Norinaga, and focused on studying the history of his native country and the development of Japanese individuality.

Country of educated people

Centralization of power

In 1871, the new government of Emperor Meiji, to prevent the collapse of his nascent power, abolished the system of han principalities and replaced them with prefectures subordinate to the center.

Before this, each of the approximately 270 principalities had its own armed forces and exercised political will within a decentralized power structure. The sudden abolition of this structure was practically a coup d'etat. The Meiji leaders decided that their government should be the sole political authority in the country so that it could fulfill the urgent task of building a modern state. The government was extremely concerned that Japan might become a colony under the control of one of the great powers. This was the fate of much of India and Southeast Asia, while China was forced to cede Hong Kong to Britain in 1842 after losing the First Opium War.

According to the government, the country needed to modernize as quickly as possible, increasing its economic power in order to strengthen its own armed forces and protect itself from invasion.

This is why many Japanese leaders and other important government officials went on Iwakura's mission, traveling, observing, and studying in the United States and Europe, just months after the revolutionary transition to the prefectural system. The mission also had many students, and its members made great contributions to the modernization of the country upon their return to Japan.

End of the century

The history of the Land of the Rising Sun in the second half of the 19th century combines traditionalism and innovation, industrial breakthroughs and dramatic social changes. They began in 1853, the year when the American president sent 4 warships to the eastern islands, demanding the establishment of international relations. American technology, new weapons, and powerful steamships delighted, impressed, and frightened the inhabitants of the archipelago so much that the Tokugawa shogunate made a historic decision to resume relations with Western countries. A year later, we signed an agreement, defining regulations for interaction between countries, and began the construction of 2 ports focused on international trade relations.

Gradually, in the second half of the century, Japan signed trade agreements with other major powers: Russia, Great Britain, and the modern Netherlands. Although the authorities faced strong opposition and were ostracized for their unconventional decisions, in the long term, opening the borders turned out to be a timely and effective decision. However, foreign policy is only part of the history of the Land of the Rising Sun in the 19th century. Conflict grew within the state, social tension increased.

An important page in the country's history opened in 1868 with the overthrow of the Tokugawa clan. The revolutionaries handed over the reins of power to Emperor Mutsuhito; the new government began a series of reforms. The authorities took into account the trends of the times: interest in Western countries, the desire to put new products into practice, a passion for learning about a different life. Most of the innovations were aimed at the bourgeoisie, the landowners, in order to make the country independent and put it on the capitalist path.

Japan greeted the end of the 19th century as a developed industrial power with a strong cultural potential and a high level of education. It became the first of its kind in the world, harmoniously combining the specifics of Western development and traditional Eastern values. On the wave of success, the country began hostilities, starting a war with China, then Russia.

Unity of East and West

Fall of the Shogunate

In June 1853, the US navy under the leadership of Matthew Perry approached the Japanese shores, which forced the Japanese to receive a message from the US President calling for trade relations. The head of the Japanese government, Abe Masahiro, guaranteed a response within a year and assembled a council of the aristocracy to discuss this demand. However, they did not come to a common opinion on this issue, and the fact that they were convened shook the authority of the shogunate. In January 1854, Perry again sailed to the Japanese Islands and, through intimidation of invasion, achieved Japanese acceptance of US terms. In accordance with the agreement, Japan opened two ports for American ships, and in addition, allowed the creation of American missions and settlements in them. A short time later, similar agreements were drawn up with the Russians (Treaty of Shimoda), the British and the French. In 1858, the Japanese government again yielded to European countries and signed the unequal Ansei contracts, which removed customs sovereignty from this eastern country.

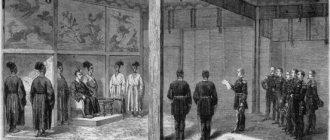

Engraving of Perry (center)

As a result of political defeats and inflation, a protest public association “Long live the Emperor, down with the barbarians!” was formed in Japan. Its leadership was persecuted by the shogunate. Among those repressed were the philosophers Yoshida Shoin and Tokugawa Nariaki. In retaliation, in 1860, the opposition killed the head of the government, the instigator of repression, which is why the authority of the shogunate fell again.

The centers of protest against the government were the western provinces of Choshu-han and Satsuma-han. Against the backdrop of xenophobic beliefs, they launched the Shimonoseki and Satsuma-British wars in 1863, but were defeated. Realizing that Japan was far behind Europe and the United States in technical terms and, having comprehended the threat of colonization, the provinces began to modernize their troops and negotiate with the emperor’s house. In 1864, to pacify the rebels, the shogunate launched the first punitive expedition against Choshu and changed his leadership. But a year later, a revolution occurred in the province, and the opposition took power into their own hands again. In 1866, with the support of Sakamoto Ryoma, Choshu and Satsuma created a secret coalition whose task was to overthrow the shogunate and revive the rule of the emperor. This helped defeat the second punitive expedition sent by the shogun to Choshu.

In 1866, the inexperienced Tokugawa Yoshinobu assumed the title of shogun. However, after the death of Emperor Komei, his fourteen-year-old son Meiji ascended the throne. The shogun sought to establish a new government instead of the shogunate, which would consist of the Kyoto nobility and provincial rulers, in which he himself would become prime minister. To do this, he renounced the title of shogun and on November 9, 1867 returned full rule to the Emperor. The anti-shogunate alliance took advantage of this, and on November 3, 1868, it unilaterally created a new leadership and, on behalf of the emperor, issued a decree to re-establish the reign of the emperor. The Tokugawa Shogunate was destroyed, and the ex-shogun lost power and lands. This coup ended the Edo period and the five-hundred-year dominance of the samurai in the Japanese government.

Shimonoseki War

Yoshinobu's Abdication

Results for Japan

The 19th century gave the Land of the Rising Sun:

- strong industry;

- capitalist direction of further development;

- social change;

- new government;

- strengthening the already powerful institution of education;

- new opportunities for citizens regardless of social class;

- international relationships;

- rapid economic growth.

Exception country

The Japanese population of the second half of the 19th century according to memoirs and works of Russian travelers

The second half of the 19th century was marked by a number of important changes in the domestic political and international situation of Japan. The country's crisis led to the forced "opening" of Japan to trade and diplomatic contacts. In 1853, permanent diplomatic relations were established between Russia and Japan, which had a certain impact on the further development of both states. Russia's attempts to establish relations with Japan have taken place since the 17th century, but were unsuccessful due to Japan's policy of self-isolation. Unlike the Western powers (USA, England, France), Russia tried to peacefully achieve the opening of Japanese ports and did not interfere in its internal affairs. Due to the strengthening of contacts between Russia and Japan in the second half of the 19th century, the country was visited by many travelers, traders, and diplomats, who left numerous travel notes, letters, and descriptions of Japan and its population. In this regard, it seems relevant to study the image of the Japanese population of the second half of the 19th century in the works and descriptions of Russians.

The body of sources is quite large; in this work, sources of personal origin and materials from periodicals were used. Among the sources of personal origin are “Travel Notes of Archpriest V. Makhov”, “Sketches with pen and pencil from a circumnavigation around the world” by A. V. Vysheslavtsev, Venyukov M. I. “Sketches of Japan”, “From the memories of two years of service in Japan” by M. I. Mechnikova, “From Memories of Japan” by A. Cherevkova, memoirs of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich and many others. The sources contain a wide variety of information about the Japanese population - character traits and mentality, information about trade, craft production, the state of the army, navy, everyday life; A characteristic feature is that the authors paid little attention to the political side of life in Japan.

The authors pay quite a lot of attention to revealing the internal qualities of the Japanese population, and for most memoirists they are approximately the same; Almost everyone names such qualities as accuracy, politeness, modesty, hard work, and curiosity. The authors consider one of the most important features to be a strong sense of patriotism and love for the motherland, for example, the Russian missionary Archimandrite Andronik writes that “every Japanese in childhood acquired the conviction that his country occupies first place in the world.” [1, p. 46]. Among the negative qualities, the authors note secrecy, cunning, and insincerity.

All Russians who visited Japan describe in great detail the daily life of the Japanese population, and during the second half of the 19th century the nature of the descriptions did not change significantly. All sources pay attention to descriptions of the homes of the Japanese, the internal arrangement of their houses, diet, clothing, etc. The Japanese family, the position of the woman in the family, children, etc. are described in detail.

The life and daily life of the Japanese is described in detail in the memoirs of Archpriest V. Makhov, who was one of the first Russians to visit Japan in 1853.

The climate and high seismicity determined the specificity of the buildings - houses in Japan were wooden, one-story, each house had a garden or front garden, window openings were covered with screens, which also served as walls between rooms. This type of housing allowed them to quickly restore buildings after devastating earthquakes and hurricanes. The houses of ordinary residents were located close to each other due to the dense population of cities and the country as a whole. There was no furniture in the houses, it was replaced by mattresses and mats, and the houses were heated by a fireplace. [6, p. 62]. Both residential and commercial buildings were built according to the same model, and the temples differed from them in their beauty. An important fact is that in the city of Edo - the capital of Japan during the era of the Tokugawa shogunate - according to Makhova, the buildings were worse than in the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate, which indicates a higher level of their development compared to the capital.

Many authors note a similar internal structure of houses; In houses, great importance was attached to the hearth, which burned continuously. It played a vital role in the life of the common population and served not only for cooking and heating, but also for family unity and strengthening psychological ties between family members. A. A. Cherevkova in her book “Memories of Japan” noted that the houses of the Japanese were not heated with anything other than burning coals and in winter it was quite cold in them; we can conclude that the Japanese thus easily tolerated the cold, as noted in the source: “... the Japanese continued to walk around in their kimonos, the fluttering hem of which revealed completely bare feet in wooden sandals, worn on thin socks. And the children, dressed in the most frivolous way, rushed through the streets, not paying any attention to the snow.” [10].

Many authors noted the obvious poverty of the Japanese diet - they ate vegetables, cereals, fish, herbs, seaweed, and rice; preference was given to hot food and drinks. V. Makhov writes: “They don’t drink cold drinks or anything uncooked at all; wood is constantly burning under the hearth, a copper kettle with water and tea hangs over the fire day and night. To the incessant drinking of tea and smoking tobacco, both men and women, and often even children, are terrible hunters.” [6, p. 64]. The Japanese practically did not eat meat, which is also mentioned in other sources, for example, Archimandrite Andronik in his memoirs argued that the reason for this was the lack of livestock and pastures among the Japanese. A. A. Cherevkova noted that many Europeans do not like Japanese food, because... fish and vegetable dishes seem bland and insufficiently nutritious to them. [10].

The clothes of the Japanese were wide robes (kimonos) made of cotton fabric and silk of different colors. In cold weather, the number of robes could reach several dozen. The clothing of the Japanese remained unchanged for centuries, and only at the end of the 19th century, already during the Meiji era, it underwent certain changes, which was associated with the desire of the emperor to change clothing in a European manner. As a result, some wealthy Japanese began to wear European clothing, but the majority of the population continued to wear traditional clothing. [9, p. 220].

A. V. Vysheslavtsev in his book “Pen and Pencil Sketches from a Trip Around the World” makes an interesting remark that even the Japanese poor had a penchant for a comfortable life, this explains their extreme cleanliness and good manners. He pays great attention to the description of the Japanese family. The Japanese got married when they were young and tried to avoid unequal marriages. The woman, as a sign of love for her chosen one and to demonstrate that she no longer wanted to attract other men, painted her teeth black: “When the bride is brought into the groom’s house, she is covered with a white veil, as a sign that she has died for her family, and should live only for her husband.” [4, p. 340]. Despite this, women in Japan, unlike women in other Asian countries of the same period of time, enjoyed respect in society and a certain freedom: “The position of women, although they are subordinate to their husbands, is more bearable here than anywhere in Asia; they take their place in society and share all pleasures with their husbands, brothers and fathers; In general, they enjoy a certain freedom, and rarely use it for evil.” [4, p. 342]. Women could leave the house, go for a walk or visit. In addition, divorce was not prohibited; women could remarry (however, this did not apply to those women who were convicted of cheating on their spouse). However, this situation of women can only be discussed in cities; Peasant women were completely dependent on men and subordinated to them. Women, along with men, received a basic education: they learned to count, write, and studied the history of Japan. In this, the position of the Japanese woman was radically different from the position of women in other countries. Women in Japan preferred bright clothes and jewelry; The author especially notes the passion of Japanese women for using cosmetics, and notes that this only spoils their faces. [4, p. 345].

Freedom of morals in relation to Japanese women is evidenced by such a source as the “Book of Memories” of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich Romanov. He spent two years in Japan, and described in his memoirs the tradition of Russian officers “taking as wives” Japanese women during their stay in Japanese cities. “Marriages” were not accompanied by official ceremonies and were concluded for a period of one to three years, then the woman could remarry or return to the family. Among the Japanese, this practice was considered normal and even encouraged: “Their relatives not only did not ostracize them for their connections with foreigners, but considered their way of life to be one of the forms of social activity open to their sex.” [2, p. 71].

Children occupied the most important place in the life of the Japanese family. M.I. Venyukov, in his study of Japan in the 19th century, gave a detailed description of the life of one Japanese resident from birth to death. The Japanese never left small children alone; they were always carried either by their mothers or older brothers or sisters on their backs, so they did not interfere with their work. At the age of five, the child’s education began. In wealthy families, children studied until they were 15 years old. An important feature of the Japanese, according to Venyukov, is their literacy and education. The author notes that in Japan, unlike Europe, “there is not a single illiterate person.” [3, p. 204]. According to the data given in the source, many young people got married at the age of 18-20, girls - at the age of 14-15. The author sees both positive and negative sides in early marriages. Early marriage helped improve the morals of Japanese society and saved young people from many vices. On the other hand, as the author writes, it contributes to a lack of height and physical strength among the Japanese, as well as premature aging of women. This fact is also cited in other sources, in particular, in the memoirs of L.I. Mechnikov: “It is difficult to meet a woman over 30 years old who is not a completely ugly old woman. Early marriage and the habit of carrying children on special supports behind the back spoil the figure of a Japanese woman early and lead to frequent curvature of the ridge.” [7, p. 85].

The daily activities of the Japanese are housekeeping and service; Their leisure time was relaxing at home, with their family. The authors note the Japanese’s great love for entertainment and visiting guests. In the summer they took country walks to contemplate nature; They had a great love for boating, dancing and music, and only women were allowed to dance. Sources note the Japanese's passion for theatrical performances. A. A. Cherevkova describes in detail her visit to the Japanese theater. The roles were performed exclusively by men, and performances could last all day. [10].

Street shows were very popular among the poor - performances by acrobats, magicians, and traveling musicians. The Japanese population had a passion for various holidays and amusements, but sources indicate that they felt quite constrained in the company of foreigners.

Thus, the sources touch on many aspects of the daily life of the Japanese population, which indicates a certain interest of the authors in this side of Japanese life. In general, we can conclude that Russian authors who wrote about Japan paid the main attention to the personal qualities of the Japanese population, describing their way of life and way of life, cities and their attractions, and relationships between the Japanese. The image that is created on the pages of sources is quite stable and has not undergone significant changes for fifty years.

Reforms in Japan in the 19th century

To gain independence, stabilize the economy, and develop capitalism in the 19th century in the Land of the Rising Sun:

- formed a regular army;

- replaced principalities with prefectures subject to centralized authority;

- abandoned the untouchable caste;

- gave samurai the right to choose a profession;

- introduced the yen;

- defined free trade;

- moved the capital to Tokyo;

- opened the University of Tokyo;

- abandoned princely, samurai property;

- land transactions were allowed;

- paid for the construction of industrial enterprises from government funds;

- adopted the Constitution.

Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895)

In 1876, Japan began the “discovery” of Korea in much the same way that the Americans “discovered” Japan itself. In Korea, she entered into an acute conflict with China, which led in 1894-1895. to the Sino-Japanese War. The battle between the two largest Far Eastern states ended in a decisive victory for Japan, which now became a leading regional power.

Japan captured Taiwan, gained its "zone of influence" in China and forced it to give up all rights to Korea. The huge indemnity received from China accelerated the industrialization of Japan and the development of its military industry. At the same time, a revision of old unequal treaties began, thanks to which Japan soon acquired equal rights with the Western powers in international relations and in world trade.

Agriculture and industry.

The agrarian reform carried out in 72-73 of the nineteenth century was quite radical. Thanks to this, private ownership of land appeared. Land plots were received by those who actually owned them at the time of the reform. These were mainly wealthy peasants. Many land owners lost their rights because they could not pay the tax and did not have the funds to buy them back. Many peasants received negligible plots of land. They had no choice but to become hired workers and tenants, some were sent to the cities.