Japan in the 19th century was one of the largest states, which is located in East Asia and consists of 4 thousand small islands. For two hundred years during the reign of the Tokugawa dynasty, the Land of the Rising Sun was completely isolated from foreign interference. This certainly had an impact on the formation of culture and the further development of Japan in the 19th century.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the country began to feel the active influence of the West. In the first half of Japan of the 17th century. The government decided to stop all contacts with the West, as they feared an invasion by Christian missionaries who could bring a large army with them. As a result, residents of Japan could not leave the country, and foreigners could not enjoy the amazing culture and nature of the Land of the Rising Sun.

Economic development of Japan

The bourgeois transformations carried out in Japan after the revolution of 1867-1868 directed the country along the path of capitalist development. The Japanese government took industrial development under its patronage, generously subsidizing the construction of enterprises and railways. The government paid special attention to the creation of the military industry. The expansion of industry was accompanied by its concentration. Two giant concerns began to play a major role in Japan:

- Mitsui and

- Mitsubishi,

competing with each other. They united banks, coal mines, factories and many other enterprises.

However, as a result of the incompleteness of the bourgeois revolution, many remnants of feudalism remained in Japan. The political sphere was dominated by an absolute monarchy. In the villages, enslaving conditions for peasants renting land from landowners continued to exist. The miserable existence of peasants and the extremely low (much lower than in Europe) wages of workers narrowed the domestic market. This circumstance strengthened the desire of Japanese capitalists to seize colonial possessions.

In order to implement an aggressive imperialist policy, the Japanese big bourgeoisie established an alliance with the samurai - the so-called Japanese nobility and the military that came from its midst.

Agriculture

With the beginning of peaceful life, the Japanese actively began to develop their agriculture. By order of the authorities, old flood fields were expanded and new ones were created by developing previously untouched virgin lands and carrying out large-scale irrigation work. During the first century of the shogunate, the area of arable land doubled. At the same time, labor productivity increased, which was facilitated by the appearance of new tools - hoes and a thousand-tooth thresher, as well as the use of fertilizers - rapeseed oil and dried sardines. The cultivation of commercial crops—cotton, hemp, rapeseed, tea, indigo dyes, and safflower—reached a wide scale.

Introduction of the Constitution in 1889 in Japan

Economic transformations in Japan led to the growth and political strengthening of the bourgeoisie, which began to lay claim to leadership in the state. A bourgeois-liberal movement began to develop in the country for the introduction of a constitution limiting the autocracy of the emperor.

The government decided to make some concessions and introduced a constitution in 1889 (see document). A parliament was created in the country, consisting of two chambers: an upper and a lower one. The upper house for the most part was not elected. It consisted of people appointed by the emperor, and of representatives of the highest nobility, who received hereditary rights to participate in the upper house. Thus, the latter resembled the English House of Lords.

The lower house was elected, but only rich people enjoyed the right to vote. The power of parliament was small, while the power of the emperor, even after the introduction of the constitution, remained enormous. Every law passed by parliament was sent to the emperor for approval in order to enter into force. The cabinet of ministers was responsible to him, and not to parliament. The emperor had the right to declare war and conclude peace. He held supreme command of the army and navy. Military circles played a very important role in the Japanese government.

The parliamentary elections took place in an atmosphere of bribery and violence. Power in Japan after the adoption of the constitution was still concentrated in the hands of the most reactionary elite of semi-feudal landowners and the big bourgeoisie.

Japan: traditions, revolution and reforms, traditionalists, revolutionaries and reformers (part 1)

The toad croaks, Where is it? passed without a trace

Spring blossoms... Xuoshi

In the history of every country, there have probably been events associated with foreign invasions that can only be described as dramatic. The fleet of the Bastard Conqueror appeared off the coast of Britain, and everyone who saw it immediately realized that this was an invasion that would be very difficult to repel. “On the twelfth day Bonaparte’s troops suddenly crossed the Neman!” - is announced at a ball in Shurochka Azarova’s house in the movie “The Hussar Ballad”, and it is immediately stopped, because everyone understands how serious a test they face. Well, we don’t need to talk about June 22, 1941. Everyone knew that something like this would definitely happen - cinema, radio, newspapers, for many years they prepared people to understand the inevitability of war and, nevertheless, when it began, it was perceived as a surprise.

This is how the Japanese lived a quiet and measured life back in 1854. Sit under a tree and admire Fuji. (Artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi 1797–1861)

The same thing happened in Japan on July 8, 1853, when in the roadstead of Suruga Bay, south of the city of Edo (today Tokyo), ships of the American squadron of Commodore Matthews Perry suddenly appeared, among which were two wheeled steam frigates. The Japanese immediately called them “black ships” (korofu-ne) for their black hulls and the plumes of smoke spewing from their chimneys. Well, the thunder of gunfire immediately showed them that the warlike guests were very serious.

Now let’s imagine what this event meant then for Japan, on whose soil for more than 200 years foreigners, one might say, were allowed... “piece by piece.” Only Dutch and Chinese merchants had the right to visit this country, and even those were allowed to open their offices only on the island of Deshima, located in the middle of Nagasaki Bay and nowhere else. Japan was considered the land of the "gods", its emperor was considered "divine" by nature. And suddenly some foreigners arrive on ships and do not ask him, lying humiliatingly in the dust, but demand to establish diplomatic relations with some far, far away country overseas, and at the same time they clearly hint that if they are told “no” , that is, the Japanese will not negotiate, the aliens’ response will be... the bombing of Edo!

"Let's live in peace!" Since the issue was of exceptional importance, the Japanese side asked for time to think. And Commodore Perry was so “generous” that he gave her not days, but several months before his next visit. And if “no,” then, they say, “the guns will start talking,” and he invited the Japanese onto his ship. Show him what they are like. Meanwhile, the Japanese were well aware of how the first “Opium War” (1840 – 1842) ended for vast China, and they understood that the “overseas devils” would do the same to them. That is why, when on February 13, 1854, Perry reappeared off the coast of Japan, the Japanese government did not quarrel with him, and on March 31, Yokohama signed the Kanagawa (named after the principality) treaty of friendship with him. The result was the most favored nation regime in trade for the United States, and several ports were opened for American ships in Japan, and American consulates were opened in them.

And then suddenly these “long-nosed barbarians” appeared. Japanese engraving of Commodore Perry, 1854 (Library of Congress)

Naturally, most of the Japanese greeted this agreement with the “overseas devils” or “southern barbarians” with extreme hostility. And how could it be otherwise, if both education and “propaganda” for centuries inspired them that only they live in the “land of the gods”, that it was they who were granted their protection, and everyone else... are... “barbarians”. And besides, everyone understood that it was not so much Emperor Komei who was to blame for what happened (since the emperor a priori cannot be guilty of anything), but rather the one who allowed this humiliation of both the country and its people, Shogun Iesada, because it was he who owned the real power in Honcho - in the Divine Country.

And even on such ships...

The Death of the Samurai Clan In his truly amazing novel “1984,” George Orwell very correctly wrote that the ruling group of society loses power for four reasons. She may be defeated by an external enemy, or she may rule so ineptly that the masses start an uprising in the country. It may also happen that, due to her shortsightedness, she allows a strong and dissatisfied group of middle people to emerge, or she has lost self-confidence and the desire to rule. All these reasons are not isolated from one another; one way or another, all four work. The ruling class that can protect itself from them holds power in its hands forever. However, the main decisive factor, according to Orwell, is the mental state of a given ruling class. In the case of the samurai clan, which ruled Japan from the moment the Tokugawa family came to dominate the country, everything was exactly the same, but the main reason why the samurai lost power was their physical degeneration. Their women were too fond of cosmetics and... whitened not only their faces and hands, but also their breasts, even when feeding babies. As a result, they licked the whitewash containing mercury. Mercury accumulated in their bodies, and from generation to generation they became increasingly weaker and lost their intellectual abilities. And the way up to representatives of other classes was practically closed. Of course, there were exceptions. They are always there. But in general, by the middle of the 19th century, the samurai clan could no longer adequately respond to the challenges of the time.

And what was there to fight with them? Even the pistols in Japan had wicks! (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

In addition, there was one more very important circumstance. Since the internecine wars in Japan ceased with the reign of the Tokugawa, most of the samurai, which amounted to approximately 5% of the country's population, were left out of work. Some of them began to engage in trade or even crafts, carefully hiding the fact that he was a samurai, since labor was considered a disgrace for a warrior; many became ronin and wandered around the country, having lost all means of subsistence, except perhaps alms. In the 18th century there were already more than 400,000 of them. They robbed, formed gangs, committed contract killings, became leaders of peasant uprisings - that is, they turned into outlaws - people outside the law. antisocial element. That is, there was obvious decomposition of the military class, which in the conditions of “eternal peace” had become useless to anyone. As a result, discontent in the country became widespread; only those who were part of the shogun's inner circle were happy.

This is how the idea arose and strengthened to transfer power from the hands of the shogun to the hands of the Mikado, so that life would return to the “good old days.” The courtiers wanted this, the peasants wanted this, they did not want to give up to 70% of the harvest, and this was also wanted by the moneylenders and traders, who owned about 60% of the country’s wealth, but who had no power in it. Even the peasants in the Tokugawa hierarchy were considered superior to them in their social status, and what kind of rich man could like such an attitude towards him?

“Death to foreign barbarians!” That is, in the middle of the 19th century in Japan, almost every third resident was dissatisfied with the authorities, and only a reason was needed for it to manifest itself. This reason was precisely the unequal treaty with the United States, which many Japanese did not accept. And at the same time, in the very fact of his imprisonment, people saw the powerlessness of the Tokugawa shogunate, and at all times and in all countries it was the custom to overthrow and drive away powerless rulers. Because the people are always impressed by action, and besides, it was simply impossible to explain to them that shogun Iesada and the head of the bakufu, Ii Naosuke, act, in general, in their interests, that is, the people. Because a tough position towards the West meant for Japan a war of extermination, in which not only masses of Japanese would die, but also the country itself. Ii Naosuke understood this well, but he did not have such power in his hands to enlighten millions of fools and dissatisfied people. Meanwhile, the bakufu concluded several more of the same unequal treaties, as a result of which, for example, it even lost the right to judge foreigners who committed a crime on its territory according to its laws.

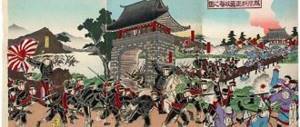

Murders of “long-noses” Discontent in thoughts always continues with discontent in words, and words very often lead to bad consequences. In Japan, they began to set fire to the houses of bakufu officials and those merchants who traded with foreigners. Finally, on March 24, 1860, right at the entrance to the shogun's castle in Edo, the samurai of the Mito domain attacked Ii Naosuke and cut off his head. This was an unheard of scandal, since before the funeral she had to be sewn to the body, since only criminals were buried without a head. Further more. Now in Japan they began to kill “long-nosed” people, that is, Europeans, which almost started a war with England. And then it came to the point that in 1862, a detachment of samurai from the Satsuma principality entered Kyoto and demanded that the shogun transfer power to the Mikado. But things did not come to an uprising. Firstly, the shogun himself was not in Kyoto, but in Edo. And secondly, the emperor did not dare to take responsibility in such a delicate matter as starting a civil war in his own country. These samurai clearly had nothing to do in the capital, and after some time they were simply taken out of the city. But the shogun took certain measures and strengthened his troops in the capital. Therefore, when a year later a detachment of samurai from the Cho-shu principality arrived in Kyoto, they were greeted with gunfire. The calm that followed these events lasted three years, until 1866, and all because people were looking closely to see whether they were doing worse or better from the changes taking place in the country.

Well, how do you like such an American woman who has penetrated your “Country of the Gods”? Artist Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1826 – 1869, fig. 1860) (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The situation was fueled by centuries-old feudal strife. After all, the samurai of the southern principalities of Satsuma, Choshu and Tosa, ever since the defeat at the Battle of Sekigahara, had been at enmity with the Tokugawa clan and could not forgive him for its consequences and their humiliation. It is interesting that they received money for weapons and provisions from traders and moneylenders directly, seemingly interested in the development of market relations in the country. The motto was chosen in accordance with the objectives of the uprising: “Reverence for the emperor and expulsion of the barbarians!” However, if everyone agreed with the first part of it, then the second part, also seemingly not disputed by anyone, was the subject of serious disagreement in details. And the whole dispute concerned only one thing: until when can concessions be made to the West? It is interesting that the leaders of the rebels, just like the bakufu government, were well aware that further continuation of the policy of isolationism would destroy their country, that Japan needed modernization, which was absolutely impossible without the experience and technology of the West. Moreover, among the samurai by that time there were already many people with education who were primarily interested in the achievements of Europeans in the field of military art. They began to create units of kiheitai ("unusual soldiers"), recruited from peasants and townspeople, whom they trained in European tactics. It was these units that then became the basis for the new Japanese regular army.

It was here that the main nest of conspirators against the shogun was located. Map of Taiwan and the domains of the daimyo of Satsuma, 1781.

However, the rebels acted separately and the shogun's army had no difficulty in dealing with them. But when the principalities of Satsuma and Choshu agreed on a military alliance, the Bakufu troops sent against them began to suffer defeat after defeat. And then, on top of everything else, in July 1866, Shogun Iemochi died.

“Give in a little to win in a big!” The new shogun Yoshinobu proved himself to be a pragmatic and responsible person. In order not to add further fuel to the fire of the civil war, he decided to come to an agreement with the opposition and ordered the suspension of hostilities. But the opposition stood its ground - all power in the country should belong to the emperor, “the end of dual power.” And then, on October 15, 1867, Yoshinobu committed a very far-sighted and wise act, which subsequently saved his life and respect from the Japanese. He renounced the powers of the shogun and declared that only imperial power, based on the will of the entire people, would guarantee Japan's revival and prosperity.

Shogun Yoshinobu in ceremonial attire. Photograph of those years. (Library of Congress)

On February 3, 1868, his abdication was approved by the emperor, who issued the “Manifesto on the Restoration of Imperial Power.” But the last shogun was left with all his lands and authorized to lead the government during the transition period. Naturally, many radicals were not happy with this turn of events. They, as happens very often, wanted a lot of everything at once, and successive steps seemed to them too slow. As a result, a whole army of dissatisfied people gathered in Kyoto, led by Saigo Takamori, known for his irreconcilable position regarding the liquidation of the Tokugawa shogunate. They demanded that the former shogun be deprived of even the ghost of power, and that all the lands of the Tokugawa clan and the treasury of the bakufu be transferred to the emperor. Yoshinobu was forced to leave the city, move to Osaka, after which, waiting for spring, he moved his army to the capital. The decisive battle took place near Osaka and lasted four whole days. The shogun's forces outnumbered the emperor's supporters three to one, and yet the disgraced shogun suffered a crushing defeat. Which is not surprising, since his soldiers had old matchlock guns, loaded from the muzzle, the rate of fire of which could not be compared with the rate of fire of the Spencer cartridge rifles used by the soldiers of the imperial army. Yoshinobu retreated to Edo, but then surrendered anyway, since he had no other choice but suicide. As a result, a large-scale civil war in Japan never began!

"New guns." Artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839 – 1892) (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The former shogun was first exiled to his family castle of Shizuoka in eastern Japan, from which he was forbidden to leave. But then the ban was lifted, a small part of his lands was returned, so he had quite a decent income. He spent the rest of his life in the small town of Numazu, located on the coast of Suruga Bay, where he grew tea, hunted wild boars and... took up photography.

Emperor Mutsuhito.

By May 1869, the emperor’s power was recognized throughout the country, and the last pockets of rebellion were suppressed. As for the events of 1867–1869 themselves, they received the name Meiji Isin (Meiji Restoration) in Japanese history. Meiji (“enlightened rule”) became the motto of the reign of the young Emperor Mutsuhito, who took the throne in 1867 and faced the difficult task of modernizing the country.

To be continued…

Japan's aggressive foreign policy

The rapid growth of Japanese capitalism was accompanied by wars of conquest. The geographical proximity of the huge but weak China and the remoteness of its major rivals gave Japanese capitalism a certain advantage. It was especially easy and convenient for the Japanese imperialists to plunder the Chinese people.

As a result of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. Japan defeated and thoroughly plundered China. However, not content with this, the Japanese imperialists began to prepare for a war with Russia for the redistribution of spheres of influence in the Far East. Japan sought to take over China

- northeastern provinces (Manchuria) and

- Korea.

The Japanese imperialists also dreamed of seizing Russian lands - the island of Sakhalin and even the entire Russian Far East. In preparation for war with Russia, Japan entered into an alliance with England in 1902.

Japanese spies and intelligence officers, taking advantage of the carelessness of the tsarist government, flooded the Far Eastern regions of Russia. Under the guise of merchants, hairdressers, laundresses, etc., they penetrated into fortified areas, found out the location of military units, their movements and combat readiness.

Japan was well prepared for war. She was provided with British and American support.

End of the century

The history of the Land of the Rising Sun in the second half of the 19th century combines traditionalism and innovation, industrial breakthroughs and dramatic social changes. They began in 1853, the year when the American president sent 4 warships to the eastern islands, demanding the establishment of international relations. American technology, new weapons, and powerful steamships delighted, impressed, and frightened the inhabitants of the archipelago so much that the Tokugawa shogunate made a historic decision to resume relations with Western countries. A year later, we signed an agreement, defining regulations for interaction between countries, and began the construction of 2 ports focused on international trade relations.

Gradually, in the second half of the century, Japan signed trade agreements with other major powers: Russia, Great Britain, and the modern Netherlands. Although the authorities faced strong opposition and were ostracized for their unconventional decisions, in the long term, opening the borders turned out to be a timely and effective decision. However, foreign policy is only part of the history of the Land of the Rising Sun in the 19th century. Conflict grew within the state, social tension increased.

An important page in the country's history opened in 1868 with the overthrow of the Tokugawa clan. The revolutionaries handed over the reins of power to Emperor Mutsuhito; the new government began a series of reforms. The authorities took into account the trends of the times: interest in Western countries, the desire to put new products into practice, a passion for learning about a different life. Most of the innovations were aimed at the bourgeoisie, the landowners, in order to make the country independent and put it on the capitalist path.

Japan greeted the end of the 19th century as a developed industrial power with a strong cultural potential and a high level of education. It became the first of its kind in the world, harmoniously combining the specifics of Western development and traditional Eastern values. On the wave of success, the country began hostilities, starting a war with China, then Russia.

Unity of East and West

Russo-Japanese War

At the beginning of 1904, the Japanese navy, without declaring war, attacked the Russian fleet in Port Arthur and sank several warships. As a result of the surprise attack, Japan achieved superiority at sea. Taking advantage of this, she transferred a significant army to Manchuria by sea, well armed with the help of England, and began to push back the tsarist troops.

Russia, due to the fault of the tsarist government, was completely unprepared for a major war on a distant front. Despite the heroism of Russian soldiers and sailors, the tsarist army and navy were defeated. It was not Russia and not the Russian people that were defeated in this war. The tsarist regime was defeated, having criminally plunged the people into an alien imperialist war and, moreover, not being prepared for it.

Having suffered defeat, the tsarist autocracy, frightened by the growth of the revolutionary movement in the country, hastened to make peace with Japan. According to the peace treaty concluded in 1905 in Portsmouth (USA), Japan captured the southern half of Sakhalin Island, the cities of Port Arthur and Dalny on the Liaodong Peninsula, previously leased by Russia from China. Russia recognized Japan's predominant influence in Korea and Southern Manchuria. Moreover, the frightened Tsar gave Japan the original Russian land -.

The Russo-Japanese War was one of the first imperialist wars for the territorial redistribution of land by the largest capitalist powers.

Influence of Western culture

The Meiji era saw changes not only in economics and politics, but also in cultural life. In 1871, a policy was proclaimed to overcome feudal backwardness and to create an “enlightened civilization” in the country. The Japanese persistently borrowed the achievements of Western culture, science and technology. Young people went to study in Europe and the United States of America. Conversely, foreign specialists were widely attracted to Japan. Professors at Japanese universities were British, Americans, French and Russians. Some fans of everything European even proposed adopting English as the national language.

“Views of Barbarian Countries” is the title of the engraving. It depicts the Port of London as it was seen by the famous Japanese artist Yoshitoro

An integral part of the transformation was school reform. Primary and secondary schools and universities were opened in the country. A law in 1872 made four-year education compulsory. Already in the early 80s. Among young Japanese it was difficult to meet an illiterate person.

By the end of the 19th century. The Japanese become aware of the best works of Western European and Russian literature. Japanese writers created a new literature that differed from the medieval one. Real life and the inner world of man were increasingly depicted. The novel genre is gaining particular popularity. The largest writer of that time was Roka Tokutomi, who was influenced by L. Tolstoy. The novel “Kuroshivo”, translated into Russian, brought him fame. In 1896, cinema was brought to Japan, and 3 years later Japanese-made films appeared.

Cover of Don Quixote, published in Japanese in 1914.

Labor movement in Japan

In Japan itself, the situation of workers in the 20th century. it was still quite difficult. The workers lived in barracks and barracks, where prison rules reigned. Often workers were kept locked in barracks. There was a case when a fire broke out in one such barracks, and out of 50 female workers locked in it, 31 died in the flames. The workers received starvation wages and worked 12-14 hours a day . There was no legislation protecting workers' rights in the country.

Japanese workers began to speak out against the arbitrariness of their employers and government. Already in the 80s they tried to organize trade unions, and in the 90s a wave of strikes and demonstrations swept across the country.

During these same years, the Japanese revolutionary Sen Katayama began promoting socialism. In 1901, with the close participation of Katayama, the Socialist Party was organized in Japan . However, the Japanese government soon passed a law dissolving it. Members of the Socialist Party were subjected to repression.

Other workers' organizations arose, despite the fact that the government imprisoned anyone suspected of belonging to them.

Revolutionary sentiments grew among the working class. During the Russo-Japanese War, advanced Japanese workers sent Russian workers a letter condemning the imperialist war. At the Congress of the Second International in Amsterdam in 1904, Katayama declared the complete solidarity of the Japanese proletariat with the Russian. He demonstratively shook hands with the representative of the Russian labor movement G. V. Plekhanov. Under the influence of the Russian Revolution, the Socialist Party was again organized in Japan in 1906. One of its prominent figures was Kotoku , who sharply criticized the reformist compromisers. True, while leading the revolutionary struggle, he himself made mistakes of an anarchist nature.

To get rid of Kotoku, who was very popular among the workers, the government accused him of plotting against the emperor. Kotoku, his wife and his closest comrades were captured and imprisoned. There they suffered a terrible fate: they were strangled.

Most of the active participants in the socialist movement were thrown into prison. Police repression dealt such a severe blow to the labor movement that it temporarily died out. It revived again under the influence of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

New in the way of life of Japanese society

Under the influence of the West, various innovations were introduced into the Japanese way of life. Instead of the traditional lunar calendar, the pan-European Gregorian calendar was introduced. Sunday was declared a day off. Railway and telegraph communications, publishing houses and printing houses appeared. Large brick houses and European-style shops were built in the cities.

Changes also affected the appearance of the Japanese. The government wanted the Japanese to appear civilized in the eyes of Europeans. In 1872, the emperor and his entourage dressed in European clothes. After that, it began to spread among the urban population and much more slowly among the rural population. But one could often see a man in a kimono and trousers. Particularly difficult was the transition to European shoes, which differed from traditional Japanese ones.

Old and new are closely intertwined on the streets of Japanese cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Old customs were prohibited only because Europeans considered them barbaric. For example, common public baths, tattoos and others.

European hairstyles gradually came into fashion. Instead of the traditional Japanese one (long hair curled into a bun on top of the head), a mandatory short haircut was introduced. The government believed that it was more suitable for the citizens of a renewed Japan. The military were the first to part with their buns and put on their uniforms. However, civilians were in no hurry. It was only after the emperor cut his hair in 1873 that three-quarters of the male population of Tokyo followed his example.

The Japanese also borrowed from the Europeans the practice of eating meat products, which they traditionally abstained from. But everything changed after the belief spread that Europeans had achieved great success thanks to the calorie content of meat foods.

The borrowing of Western culture sometimes developed into a negative attitude towards one’s own—national culture. There were cases of destruction of historical monuments and burning of ancient temples. But the fascination with everything European in Japan was short-lived.

DOCUMENTS AND MATERIALS - FROM THE CONSTITUTION OF 1889

- Art. 1. The Japanese Empire is ruled by a continuous imperial dynasty for eternity...

- Art. 5. The Emperor exercises legislative power in agreement with the Imperial Parliament...

- Art. Yu. The Emperor establishes the organization of the various branches of government, appoints and dismisses all civil and military officials and determines their salaries...

- Art. 11. The Emperor is the supreme commander of the army and navy...

- Art. 13. The Emperor declares war, establishes peace and concludes treaties...

- Art. 33. The Imperial Parliament consists of two houses: the House of Peers and

- Chamber of Deputies...

- Art. 34. The House of Peers consists of members of the imperial family, holders of noble titles and persons appointed to it by the emperor...

- Art. 55. Each of the ministers of state gives his advice to the emperor and is responsible to him for them.

- All laws, imperial decrees and acts of every kind concerning public affairs must be sealed by the minister of state.

- Art. 56. The Privy Council discusses, in accordance with the regulations concerning the organization of the Privy Council, the most important state affairs when the Emperor requests it...:

- “Constitutions and legislative acts of bourgeois states”, vol. I, M., 1938, pp. 190-197.

Dates to remember

- 1904-1905 — Russo-Japanese War,

- < REVOLUTIONS IN IRAN AND TURKEY AT THE BEGINNING OF THE XX CENTURY

- -> PHOTOS OF WARFARE SHIPS OF THE IMPERIALIST STATES AT THE TURN OF THE 19th-20th CENTURIES, PAINTED AND DIGITIZED IN COLOR 1860 TO 1918 (WORK BY A JAPANESE IROOTOKO) >

Sela

The Japanese economy of the Edo era was semi-subsistence in nature and dependent on tribute rice supplies. Its collection was carried out in villages by local officials - village heads nanusi or shoya, heads of fives and peasant delegates who controlled communal arable land, mountains and waters, and also performed various administrative functions. Decisions were made collectively. Residents of the villages were divided into fives, their members were in mutual responsibility, jointly paying tribute and preventing the commission of crimes. In one village, there were customs of mutual assistance between the fives.

Finished works on a similar topic

Coursework Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 420 ₽ Abstract Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 250 ₽ Test paper Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 230 ₽

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

In order to stabilize the supply of tribute in rice, the shogunate banned the sale of land and limited the peasants, concentrating them exclusively on field work and various duties. Most villages paid taxes on time, considering them a matter of national importance. However, sometimes exorbitant exactions forced peasants to complain to the daimyo or directly to the shogun, or, in extreme cases, to start peasant uprisings.

Crisis of the Tokugawa Shogunate

In the first half of the 19th century. Many European countries have embarked on the path of industrial development. Japan, in contrast, remained a backward feudal country. Supreme power was still in the hands of military rulers - shoguns from the Tokugawa princely family. The imperial family was under their control and did not take part in government. The policy of “closing” the country, or isolating it from the outside world, continued to be pursued. European ships have long plied the seas and oceans, sailing to the most remote corners of the Earth. The Japanese did not have their own fleet and had only small fishing boats.

The economic situation of the country with its 30 million population was very difficult. The area of cultivated land did not expand, remaining the same as it was at the beginning of the 18th century. The harvest of rice, the staple food, did not increase. The birth rate exceeded the death rate by only one percent per year. The crop failure of the 1930s turned into a terrible tragedy for the Japanese. XIX century

Feudal Japan, which will soon disappear

As a result of the famine, about 1 million people died. It is not surprising that peasant and urban uprisings literally shook Tokugawa Japan. There were a total of them in the first half of the 19th century. about one thousand occurred. The masses, in their own plebeian way, sought justice and a better life. Representatives of the samurai class also went bankrupt, especially those who received meager rations of rice from the shogun and princes for military service. Finding no use for themselves, the samurai wandered around the country in search of a means of subsistence.

At the same time, they often led the protests of the peasant and urban poor. Where, in the history of what other country can this be found?