Imagine saying “thank you” in perfect Japanese to a nice waiter and seeing a surprised smile on his face. Or ask for the bill like a local, even though this is your first visit to Japan. It will be great, right? Your next trip to Japan can be twice as interesting if you know some Japanese, which you can learn thoroughly by attending a language school in Japan. You'll have a lot more fun when you can interact with the locals without the awkward grunting and waving of your arms.

The good news is that you don't have to spend months or even weeks learning Japanese—all you need to know are a few simple (and very user-friendly) phrases that you can read in minutes and master in a few days. Of course, a few memorized phrases cannot be compared with the amount of knowledge that you can get by going to study at a language school in Japan, the cost of which largely depends on the training program. However, even some phrases will significantly help in the first days of your stay in Japan. Once you've mastered these phrases, you'll be able to use them expertly, and your new Japanese friends will be delighted.

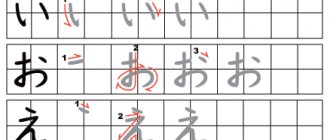

Note: Desu and masu are pronounced "des", as in the English word "desk" and "mas", as in the English word "mask". Well, unless you're an anime character. The particle は is pronounced "wa".

Hello!

Ohayo (good morning) おはよう

Konichiwa (good afternoon)

Konbanwa (good evening)

In Japan, people usually do not say "hello" but greet each other depending on the time of day. Say "Ohayo" in the morning and "Konichiwa" in the afternoon. From 18:00 onwards use "konbanwa". Note that konbanwa is a greeting and is not used to say goodnight - the word for that is oyasumi. If you confuse these two words, you will receive laughter or strange looks in response. Don't ask me how I know.

Greetings, general expressions

Good morning Ohayo: gozaimas Good evening Kombanwa Good night Oyasumi nasai Hello, how are you? Konnichiwa, o-genki des ka? Thank you, everything is fine Genki des Goodbye! Sae: nara Please excuse me Sumimasen My name is... Watashi wa... des Nice to meet you. My name is Kimura. I ask you to love and favor Hajimemashite. Watashi wa Kimura desu. Do:zo yoroshiku.Thank you Arigato I want to change money O-kane-o ryo:gae shitai de I don’t understand Wakarimasen Do you understand English?Anata wa eigo ga wakarimasu ka?I’m not very comfortable...Totto tsugo: ga waruin desu ga...Are you Mr. Tanaka? Yes. Ya TanakaAnata wa Tanaka-san desu ka? Hi. so: desu. Watashi wa Tanaka desu'Allo, this is Mr. Tanaka's apartment? Moshimoshi. Tanaka-san no o-taku desu ka? No. I'm not Japanese Iie, Watashi wa Nihonjin jya nai. I'm RussianWatashi wa Roshiajin desu DaHaiNet Iie Thank you very much Do: mo arigato: gozaimas Thank you Taihen arigato: gozaimas You're welcome Do: itashimasite No thanks O-rei niwa oyobimasen Nothing, don't worry Nandemo arimasen Thanks for the service Go-ku ro: sama deshita Thanks for the invitation Go-sho : tai arigato: gozaimas What is your name? Nan toyu: o-namae des-ka? Please tell me Totto sumimasen ga Please come in O-hairi kudasai This way, please Do: zō koutirae do: zō What is your first and last name? O-namae to myo: dzi-wa nan -to iimas-ka?Thank you for the warm welcomeGo-shinsetsu arigatoCan you help me?Onegai itashimas?I want to invite you to RussiaRussia ni go-sho: tai shitai to omoimasI want to invite you to the RestaurantResutoran ni go-sho: tai shitai to omoimasThank you for help (for cooperation) Go-kyo: ryoku arigato: gozaimas Thanks for the gift Presento arigato: gozaimas What is this? Kore wa nan des-ka? Why? Naze des-ka? Where? Doko des-ka? Who is it? Kono hito wa Donata des -ka?I'm thirstyNodo ga kawakimashitaI'm hungry (I'm hungry)O-naka ga suiteimasI'm lostMiti ni mayottaYaWatashiYou(you)AnataOnKareSheKanojoWomanJoseiManDanseiBigOokySmallChisaiHotAtsuiColdSamuiHotAtakaiColdTsumetaiGood iiIiBadWarui Let's take a photo together Isshoni shasin-o torimasho Call an interpreter Tsu: yaku-o yonde kudasai Please speak more slowly Mo: sukoshi yukkuri itte kudasaiThank you

Arigato gozaimas ありがとうございます。

Saying "arigato" without "gozaimas" to strangers such as a cashier or waiter is a bit careless. As a foreigner you can get away with it, but the more natural expression in this case is “arigato gozaimas”. Say it when you get change or when someone, for example, helps you find a vending machine or gives you directions to a language school in Japan.

I'm sorry

Sumimasen

If you only need to remember one phrase in Japanese, this is it. This is a magic phrase. You can use it in almost any situation. Accidentally stepped on someone's foot? Sumimasen! Trying to get the waiter's attention? Sumimasen! Is someone holding the elevator door for you? Sumimasen! The waitress at the cafe brought you a drink? Sumimasen! Don't know what to say? You guessed it - sumimasen.

But wait, why should I apologize to the person serving me the drink, you ask? Good question. The thing is, the word "sumimasen" is essentially an acknowledgment that you are bothering or inconveniencing someone. Thus, the legendary Japanese politeness is partly true, even if it is superficial. You can (and should) say "sumimasen" before any of the phrases below.

In transport

| Phrase in Russian | Translation | Pronunciation |

| Call a taxi | Takushi-o yonde kudasai | |

| I want to go to... | ...ni Ikitai des | |

| I need to hurry | Isoganakereba narimasen | |

| I am late | Okuremas | |

| What type of transport is most convenient to get to the city? | mati-e iku niva donna ko:tsu:kikan-ga benri desho: ka? | |

| When does the bus leave for the city? | mati-e iku basu-wa itsu demas ka? | |

| How much does a bus ticket to the city cost? | mati-made-no basu-no kip-pu-wa ikura des ka? | |

| What is the approximate cost for a taxi to the city? | machi-made takushi: dai-wa ikura gurai kakarimas ka? | |

| Where is the taxi stand? | Takushi: -no noriba-wa doko des ka? | |

| Taxi rank is in front of the airport building. | takushi: no noriba-wa ku:ko: biru no mae des | |

| To me in the center. | tu:singai-made | |

| Please take it to this address | kono ju: sho-made, kudasai | |

| How much do I have to pay? | Ikura des ka | |

| boarding pass | to:deyo:ken | |

| money | o-kane | |

| After how many stops will there be...? | ...-wa, ikutsu me no teiryushjo des ka? | |

| What's the next stop? | tsugi-wa, doko des ka? | |

| Can this bus take you to the city center? | kono basu-va, tosin-o to: rimas ka? | |

| Please notify me when there is a stop…. | ... tei-re:ze-ni tsuitara o-shiete kudasai | |

| How long does it take by metro (bus) from here to ...? | koko kara...ma-de wa chikatetsu (basu)-de nampun gurai kakarimas ka? | |

| It's a twenty minute drive. | Niju: pun gurai kakarimas. | |

| How much does a ticket cost to... | ... made no kippu-wa, ikura des ka? | |

| One ticket to... | ... made no kippu o itimai kudasai | |

| I want to take a taxi. Where is the taxi stand? | takushi: -o hiroi tai no des ga, noriba-wa doko des ka? | |

| Stop. | tomete kudasai |

Can I have the bill please?

O-kaikei onegai shimas

Use this phrase in places like izakayas, but if you find the bill on your table, there's no need to ask. Just pay for it.

“Onegai shimas” is another very convenient phrase. Use it like "please." You can use it whenever you ask for something, such as a bill. Just replace the word o-kaikei in the example above with whatever you need, such as "Sumimasen, o-mizu onegai shimas." (Can I ask for some water please?)

Japanese language and anime.

wow...

LANGUAGE AND SPEECH OF THE JAPANESE

Needless to say, the vast majority of people in Japan are Japanese, and so naturally speak and write Japanese. Other languages, including, contrary to popular belief, English, are used to an extremely limited extent in Japan.

"Do you speak Japanese?"

To the ear, Japanese speech is very pleasant and musical: simple pronunciation, an abundance of vowels, including long ones, and the absence of sharp intonation changes - all this makes it look like a smooth murmuring stream of sounds. At first it seems that speaking Japanese is quite easy. However, a European who begins to study Japanese very soon becomes convinced that it is completely different from all other languages known to him.

First of all, as it turns out, this language contains almost nothing that is usually taught in foreign language classes at school. Of course, like other languages, Japanese has nouns, adjectives, and verbs. But they look exotic: nouns have no articles, no cases, no plural, no gender. Verbs have no gender, no person, no plural, no future tense, only past and non-past. Most adjectives closely resemble verbs, in particular, they have a past tense. They, like verbs, have no future.

But if these circumstances, albeit with a stretch, can be attributed to the advantages of the Japanese language from the point of view of a person starting to learn it, then in other respects, complete disadvantages await a beginner. First of all, this is, of course, writing.

Japanese letter

For writing, the Japanese use special characters - hieroglyphs, borrowed from China back in the 6th century. In Japanese they are called “Chinese characters” (kanji). It was in China that these pictures were “constructed” more than four thousand years ago, and they are still used to write not only in this country, but also in Japan and South Korea.

A hieroglyph is a sign of a fixed outline, to which a certain independent meaning and a certain reading are assigned. While maintaining a common or similar spelling of hieroglyphs, their readings in different languages may be different. So, seeing a separate sign of four lines, a Chinese will read it as “fan”, a Korean as “pom”, a Japanese as “inu”, but they will all associate it with the concept that is conveyed in Russian by the word “dog” .

How many characters are there in Japanese? Judging by large dictionaries, there are a frighteningly large number of them, from 40 to 50 thousand. However, in reality, only a small part of them is used in ordinary texts - a little more than 2000 characters. There is a list of “everyday characters” approved by the Japanese government, which contains 1945 characters. Ideally, this is exactly how many (and similar) signs a 15-year-old Japanese high school graduate should remember. In general, according to Japanese estimates, in order to understand the meaning of 95 percent of ordinary texts, you need to know 2,000 characters.

2000 characters - is it a lot or a little? Of course, compared to the alphabets of European languages, which contain two to three dozen letters, this is an impressive number. On the other hand, a person freely retains such a number of objects in his memory - anyone can check this by making a list of people whose names and surnames he remembers by heart. There will probably not be a thousand names in it.

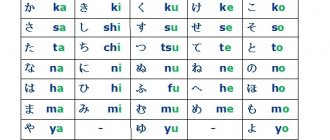

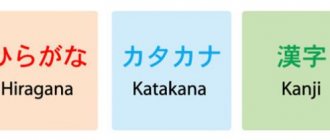

It is known that in China several tens of thousands of characters are actively used for writing. How do the Japanese get by with two thousand? The fact is that, fighting the invasion of “Chinese signs,” the Japanese, by the 10th century, based on the simplified writing of a number of hieroglyphs, created their own kana syllabary alphabet, in which each character corresponds to one syllable. Nowadays there are even two such alphabets: one with smooth, rounded outlines of characters (hiragana), the other more “angular” (katakana). Unlike hieroglyphs, the signs of the syllabary alphabet by themselves do not carry any meaning; meaning appears only after they are arranged in sequences that correspond to the sound of Japanese words. Nowadays, as a rule, unchangeable parts of words are written in hieroglyphs, changeable parts are written in hiragana, and borrowings from European languages are written in katakana. However, many Japanese words are written only in alphabet.

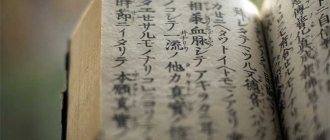

The fact that there are two alphabets is not surprising. If you look closely, writing in Russian also has two systems of signs - uppercase and lowercase letters, the styles of which sometimes differ quite significantly. There are no capital letters in Japanese text; all characters - hieroglyphs, katakana and hiragana - are approximately the same size and flow in a continuous stream; spaces between words are not accepted. If you consider that the Japanese text is sometimes diluted with Arabic and Roman numerals, as well as foreign words written in Latin letters (by analogy with the “Chinese signs” of kanji, the Japanese call them “Roman characters” - romaji), then it is easy to imagine the horror evokes this cocktail in a person who has just begun to study the Japanese language.

But the difficulties don't end there. Very soon, a beginner learning Japanese will learn that in general any Japanese word can be written in syllabic characters. Why, one might ask, are hieroglyphs needed then? Isn’t it easier to write, if not in Latin letters, then at least with the signs of your own Japanese syllabary alphabet, which has become familiar over a thousand years? Will the Japanese soon give up hieroglyphs?

Unfortunately for students, the answer to this question is no. The Japanese, apparently, will never give up hieroglyphs. To do this means to break the entire structure of the native language that has been built over hundreds of years, that is, ultimately, to cease to be Japanese.

To understand why this is so, we need to look back to the distant history of the borrowing of hieroglyphs from China in the 6th century. At that time, China stood at a much higher level of cultural development than its neighbors on the Asian mainland. It was already an ancient country with an extensive system of government, with bureaucracy, and, of course, with its own hieroglyphic writing, “designed” two thousand years earlier specifically for the characteristics of the Chinese language.

The Japanese language in those ancient times did not have its own written language, and therefore Japanese words were initially written in Chinese characters, signs of a completely different language, with a different pronunciation and grammar. The simplest of the difficulties that arise can be easily understood by anyone who tries to write down the Russian word “yet” in English transcription.

In addition, the Japanese did not perceive Chinese words well and distorted them in accordance with the norms of their pronunciation. So, for example, the Chinese reading of the character for “dog” (“fan”) in Japanese lips turned into “ken”. What also greatly “ruined life” for the Japanese was the fact that, along with the new writing, the Chinese gave them a lot of new concepts that simply did not exist in the Japanese language before. For example, along with the hieroglyph “dog,” the term “fanju” (Japanese “kenju”), which means “cynicism,” entered the language. Therefore, very soon the literate (half-Chinese) Japanese were faced with the question: how, after all, should the hieroglyph denoting the concept of “dog” be read? If in Japanese it is “inu”, then Chinese borrowings will be pronounced incorrectly. If in Chinese (“ken”), then you will have to forget the purely Japanese word.

The solution was found to be flexible in Japanese. Gradually, it was tacitly agreed that each “Chinese sign” could have more than one reading: in native words it is read in Japanese, and in Chinese borrowings it is read in Chinese, or, more precisely, in the way the Japanese hear Chinese pronunciation. Now most characters have the so-called “Chinese” reading (on-yomi) and the “Japanese” reading (kun-yomi). The general rules now are as follows: if the hieroglyphs are in a group, then they are read in Chinese readings, if individually, surrounded by the alphabet, then in Japanese. However, there are more than enough exceptions to these rules.

The situation “one sign - several readings” also exists in other languages, but rather as an exotic phenomenon rather than as an integral feature. Let’s say, if in some place in a Russian text there is a sign “3”, then in principle it can be read as “ze” or “three” - it all depends on the signs standing next to it.

In Japanese, this is not the exception, but the rule. Many characters have several Chinese readings because they were borrowed at different times and from different regions of China, where the pronunciations differ.

This is how a writing system, unique in world practice, has developed, which causes numbness and prostration in all those beginning to study the Japanese language: not only is the solid Japanese text replete with numerous “furry” icons, but they are read differently depending on what is standing around one sign or another.

It is impossible to abandon hieroglyphs for this reason: when borrowing, the Japanese lost Chinese intonation, and as a result, a lot of words were formed in Japanese that sound the same, but are written in different hieroglyphs. For example, if you open a Japanese phonetic dictionary, you will find about a dozen words borrowed from Chinese that are read “kosho”. Their meanings are very different, depending on what hieroglyphs are used. There are words here that mean “light”, “negotiations”, “official announcement”, “minister of education”, etc. Chinese people can distinguish such words by ear because they are pronounced with different intonations in Chinese. The Japanese distinguish them only when they are written down, and written down in hieroglyphs. If you write these words down in alphabet or just read them out loud, then without context it will be completely unclear to the Japanese what kind of “kosho” we are talking about.

From this it is clear that in the foreseeable future the Japanese language will not be able to do without hieroglyphs. Of course, even now a large number of identically sounding words creates a lot of problems for the Japanese. Almost any article from a Russian or, say, English newspaper can be read on the radio and listeners for whom these languages are native will understand what is being said. The Japanese State Broadcasting Corporation has a special service that “translates” newspaper articles into spoken language, selecting synonyms and eliminating similar-sounding words from the text that listeners may misunderstand.

“It never happens that there are no problems”

But, as the advertisements say, “that’s not all.” The difficulties of hieroglyphs completely pale in comparison to the peculiarities of the use of language by the Japanese themselves in speech and writing.

First of all, it should be noted that the Japanese language is characterized by a special structure of utterances, the center of which is always the interlocutor. Let's give a simple example: if you ask a question containing a negation like “Is this not your briefcase?”, then the usual answer in Russian will be “No, not mine.” Approximately the same statement will be constructed in English, German, and Spanish. The Japanese will certainly answer: “Yes, not mine.” The point here is the special attitude of the Japanese towards his interlocutor. If the European’s answer concentrates on himself and implies something like “No, not mine (this is a briefcase, and everything else does not concern me),” then the Japanese answer is built around the questioner and confirms that he is right. And if we are talking about confirmation, then, of course, from the Japanese point of view, you need to say “yes”: “Yes, (you are absolutely right), this is not my (portfolio).” In other words, in a Japanese answer, everything is subordinated to the task of maximizing the response to the interlocutor’s question, the task of providing maximum attention, and showing courtesy to the partner.

Hence the extraordinary number of polite words and forms of politeness in the Japanese language; This is why the Japanese in speech (and especially in writing) constantly elevates his interlocutor and belittles himself. About the interlocutor it is said: Your honorable name (sommei), Your fragrant name (gohomei), Your precious letter (gyokuon), Your honorable wife (reifujin). They say about themselves: my inept work (sessaku), my stupid sister (gumai), my pitiful home (settaku), although in reality for the Japanese everything may not be as hopeless as he says.

It is estimated that over the course of its centuries-old history, the Japanese language has created about 50 forms of address in the respectful-official, high, neutral, reduced, friendly polite, modest, familiar styles, about 50 forms of greetings, 40 forms of farewell, 20 forms of apologies, etc. Remembering them all and applying them correctly depending on the situation is an extremely difficult task, in order to cope with it you need to be Japanese.

Japanese grammar allows you to construct your speech literally by looking at the expression on the interlocutor’s face, monitoring his reaction, because the rules are such that the final word, most often the predicate, gives a positive or negative meaning to a statement. When you listen to a Japanese speaker, you first learn “who”, “what”, “when”, “where”, “why”, and at the very end - “did” or “didn’t do”. So in Japanese it is quite possible to construct statements in such a way as to begin with health and end with peace: not only formally and grammatically, but also in the essence of the language, this will be completely correct.

The Japanese make extensive use of these features of their native language. A real historical case is usually cited as a classic example of this approach. The military ruler of Japan, the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa house, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751), once condemning at a military council the actions of the rulers of one of the regions, during his lengthy statement he suddenly noticed from the faces of other military leaders that this condemnation would not be accepted by them , and, therefore, will complicate the situation. And Yoshimune managed at the last moment to change the meaning of the entire statement to the exact opposite, for which he only needed to change the form of the last word: “arumai” (“is not”) to “aro” (“probably is”).

The deliberate vagueness of statements is also associated with a special attitude towards the interlocutor. It is considered impolite to clearly formulate your point of view, because this means imposing it on your interlocutor. The interlocutor’s opinion may be different, and therefore the harsh wording will be unpleasant to him. Having the habit of expressing themselves unclearly, acquired with their mother’s milk, the Japanese, at least on a subconscious level, expect this from others, and therefore are amazed at the “unaesthetic” and rudeness of the direct statements of Europeans, especially those of them who consider “cutting” to be a sign of valor. “the truth” and tell your interlocutor to his face everything he thinks. From the Japanese point of view, this manner of expression looks boorish and arrogant.

In order to emphasize the non-categorical nature of statements, the Japanese often use chains of negations. You can, of course, say: “There are problems” (mondai ga aru), but a Japanese would most likely say: “It’s not possible that there are no problems” (mondai wa nai koto wa nai). It seems too simple and straightforward for a Japanese to say, “I agree,” and he says, using four negatives in a row, “It is not that it is not that I do not disagree” (fusansei de nai to iu koto de mo naku wa nai).

Polite refusal

In general, communication with the Japanese is fraught with many mysteries for a foreigner, who soon becomes convinced that the Japanese are very reserved in expressing their opinions and desires, and the statements of the inhabitants of the land of the rising sun are often very far from their direct meaning. Such “gaps” can be so large that they raise suspicions of hypocrisy among foreigners. In particular, it is absolutely impossible to get an explicit refusal from a Japanese person. Instead, figures of silence, unexpected transfers of conversation to another topic, vague statements and similar means are abundantly used.

But even the “positive” statements of the Japanese often cannot be deciphered. So, for example, an invitation like “Come visit me sometime” most likely simply means “I think you’re a good person.” The phrase “Let's have a drink together the next time we meet” means “I wouldn't mind having a drink with you if I ever meet.” Finally, if a Japanese person says, “I'll think carefully about everything you told me and will let you know one way or another,” what he really means is, “You should consider a more suitable invitation,” that's a polite refusal in Japanese. .

When all this reaches the consciousness of a foreigner, he becomes completely bewildered, not understanding how one can even talk, much less achieve mutual understanding, with the Japanese. However, the salvation is that the Japanese behave this way only with a stranger, and as the acquaintance continues, if the guest managed to win them over, they become more and more friendly and benevolent. Another thing is that this is a very, very slow process.

"English"

Many researchers note that when communicating with the Japanese, it is extremely desirable to know at least the basics of the Japanese language and be able to pronounce at least a few commonly used phrases. The Japanese sees this as respect for him and his country, which will certainly endear him to the guest. If learning Japanese is a matter of the future, then most often you have to communicate in English. Almost all Japanese study English to some degree in school, but, as a rule, have little speaking practice and have difficulty communicating. Therefore, when trying to communicate with a Japanese in English, it is better to speak slowly and clearly, and if there was no understanding, then sometimes it is useful to write what you want to say: this way the foreigner will perhaps be understood faster. For all that, as Japanese researchers themselves note, the Japanese take great pleasure in showing that they are able to communicate with a foreigner in his native language (and they most often consider English to be such) and they speak without being embarrassed by their pronunciation and mistakes and are happy when they are understood.

“... yes there is a hint in it”

As already mentioned, in a conversation the Japanese constantly belittles himself and “raises” his interlocutor. When communicating with an unfamiliar foreigner, this feature is expressed even more clearly. Therefore, there is no need, for example, to blindly take on faith the words of a Japanese person that his salary is small, his house is inferior, his wife is ugly, his children are hog-eaters, etc. The guest will be unpleasantly surprised when he is greeted by a beautiful Japanese woman on the threshold of a mansion owned by a “poor man,” and the children, as it turns out, are studying at one of the best universities in the country. It is also hardly worth puffing up from the consciousness of one’s own exclusivity when the Japanese note that a guest speaks excellent Japanese or learned to eat with chopsticks remarkably well during his two days in the country. This is nothing more than a tribute to politeness, as the Japanese understand it.

It’s probably best to approach all this with a proper dose of humor, which the Japanese also appreciate, although here it should be noted that Japanese humor is very different from ours. Therefore, trying to tell our jokes to the Japanese is an almost useless exercise. They have a completely different system of values and realities, so our hints are incomprehensible to them.

And a European will not see a hint where it is in the speech of a Japanese, and which other Japanese will easily understand. The exquisite praise of a neighbor's daughter, who began to study music, the words that such a talented girl will undoubtedly achieve a lot as a pianist in the future, is in fact a complaint, understandable to every Japanese, that all the neighbors have no peace from her playing.

To illustrate the Japanese’s penchant for allegory, our famous Japanese scholar Professor S.V. Neverov cites the story of an American student who interned in Japan and lived in the house of her Japanese friend. Both girls were fond of Japanese theater and regularly attended performances of traditional Kabuki theater, and then heatedly discussed what they saw. With Japanese houses closely packed and sliding doors open wide in the summer, the emotional speech of the American woman carried very far and disturbed the peace of the neighbors. One of the neighbors, having finally decided to express general complaints, once turned to the American woman, saying: “It’s so good that you have such a friend, one can only envy how willingly you talk until late, exchanging impressions that you have accumulated.” All this was said with a smile, in the most benevolent tone. The American, taking this as a high assessment of their friendship, began to sincerely praise her friend. It became clear to the neighbor that her words did not reach their goal. I had to talk again, in approximately the same words, this time with a Japanese friend. When the true meaning of this conversation was explained to the American woman, she was stunned, saying only: “I’ve been studying Japan and the Japanese language for so many years, but how difficult it is to understand the soul of a Japanese person!”

Is there an English menu)?

(Eigo no menu) wa arimas ka? (えいごのめにゅう)はありますか?

Sometimes you are in a hurry and need to find a certain item in the store. Instead of rushing around looking for an item, you can simply stop at the information desk or ask the nearest employee if the item is in the store. Ask this question in Japanese and they will show you where what you are looking for is located.

This phrase works great for restaurants too. If the entire menu is in Japanese, don't point your finger at it randomly. Just ask the waiter if they have something you would like to eat, such as chicken (tori), fish (sakana) or strawberry ramen (sutoroberi ramen). Just replace the words in brackets with whatever you like.

Where did the word "arigato" come from?

The other day I came across this saying of Buddha in a book:

[ひとにうまるるはかたく、いませいめいあるはありがたく、よにほとけあるはかたく]

This is the 182nd verse of the Dhammapada, translated as: “It is difficult to become a man; the life of mortals is difficult; it is difficult to listen to the true Dhamma; the birth of an enlightened one is difficult.”

Let us leave aside the teachings of the Buddha and look at this saying with purely linguistic curiosity. “Difficult” here is expressed by the words 難く and 有難く.

You most likely know what the hieroglyph 難 means: 難しい, muzukasiya - “difficult, complex” (here in the form 難い, katai). But 有難く is painfully reminiscent of the Japanese “thank you”, written in hieroglyphs: 有難う, arigato:.

I decided to explore this question and find out where this word of gratitude originated and how it relates to the concept of “difficulty”.

Sources say that the word "arigato" is of Buddhist origin, and refer us to the ancient parable of the blind turtle and the drifting log.

Once Buddha Shakyamuni asked his disciple Ananda how he felt about being born a human. “I am very happy about this,” Ananda replied. “How happy are you about this?” - Buddha asked again. Ananda became thoughtful, and then Shakyamuni depicted the following allegory.