According to the prevailing image in the West, samurai are valiant knights with iron principles who once lived in Japan. In fact, they were cruel mercenaries, sodomy was the rule among them, and profit was the main goal. And the Bushido code, which is so often referred to, is just a story invented by a Japanese who did not know the history of his country, and his ideas were subsequently successfully applied by militaristic ideologists.

Speaking about Japanese kamikazes of World War II, and in particular about the “father of kamikazes,” samurai Onishi Takijiro, it is often noted that they did not bring anything new to Japanese culture. After all, a samurai must die for his master bravely, willingly and with a smile on his face - as the Bushido code says! This is not entirely true: the kamikaze’s courage was perhaps unique in itself. And you have no idea how off-topic the Bushido code is here.

It is alleged that the code of Bushido (from Japanese - “the way of the warrior”) was formed in the 16th and 17th centuries. It contains the classic rules of samurai behavior and establishes his concepts of honor and duty. There is no single text of the code - it is as unwritten as the ancient set of rules “The Way of the Bow and the Horse” (“Kyuba no Michi”). But if the latter is mentioned in ancient Japanese texts, then we will not find any references to Bushido. After all, this code did not exist until the beginning of the 20th century, until it was invented by the Japanese writer Nitobe Inazo.

Samurai means “servant” in Japanese. They appeared in medieval Japan as a fighting force under their leaders. The relationship between the samurai and their masters was similar to the relationship between a squad and a prince. By the beginning of the 17th century, feudal wars in Japan ended with the unification of the country under the rule of the Tokugawa clan - the Edo era began, named after the clan's capital, Edo (present-day Tokyo). This era became the “golden age” of the samurai. Paradoxically, at the same time there was a decline in the class, which was completely eroded by the end of Edo, the mid-19th century.

Half a century later, Nitobe Inazo would make a career out of tales of noble and principled samurai, which later became an integral part of the Western cultural image of Japan. Here are some examples.

In the legendary 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai, Japanese camp commander Colonel Saito says to English officer Nicholson in response to his mention of the principles of the Geneva Convention: “What do you even know about the Soldier’s Code? About Bushido? Nothing! You are not worthy to command!

“Vostochka” has always attracted Europeans and had good commercial potential, which the authors of an increasing number of films and even video games began to use. In 1983, Enebel released one of the first 2D fighting games, called Bushido: Way of The Warrior. Let's not forget about Star Wars - the principles of the Jedi were largely built by Lucas on Bushido. Consider the scene from episode 4 where Darth Vader kills Obi-Wan: “You cannot win, Darth,” Obi-Wan says. “If you defeat me, I will become so strong that you cannot even imagine it” is a clear allusion to samurai honor, which remains untarnished only in case of death according to the principles of Bushido - death in loyalty to one’s principles and master. Let me remind you that Star Wars is largely based on Japanese culture and aesthetics as understood by George Lucas - for example, Darth Vader's helmet is modeled after a samurai helmet.

In the film “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise and Ken Watanabe, Watanabe’s hero, the brave samurai Katsumoto, shows miracles of nobility towards even his enemies and demonstrates high fighting spirit and fearlessness - “like a true samurai.” If the heroes really followed the true samurai traditions, then, as an English-speaking researcher of the issue aptly notes, the film should have had a love line, or even an erotic scene between the heroes of Cruise and Watanabe... What? Yes, our ideas about samurai are distorted to such an extent. But first things first.

Christian samurai

Nitobe Inazo

Nitobe was born in 1862 into an impoverished samurai family in Iwate Prefecture, a remote northern region of Japan. From the age of 9 he lived in Tokyo and studied a new subject for that time - English. Since 1877, Nitobe has been studying at an agricultural college in the even more northern prefecture of Hokkaido. In 1884 he moved to the USA. And it seems that he already knows the English language and culture better than Japanese.

At the same time, the Japanese realized how backward they were from European society and began major reforms, part of which was the deprivation of the samurai class of former privileges. Huge steps forward were the victorious wars - the Japanese-Chinese (1894-1895) and the Russian-Japanese (1904-1905). They proved to the Japanese that the abolition of samurai privileges and the restructuring of both the army and the entire society were really bearing fruit. But Europe still perceived the Japanese as a savage nation living under a feudal system. Nitobe decided to play on this, and in 1899 he published the book “Bushido. The Soul of Japan" - and written immediately in English.

Cover of the first edition of the book

Let's open the full text of the book. It's amazing how many authors reference Bushido and Nitobe's book, considering that Nitobe himself almost never cites Japanese literature or sources. The book begins with three epigraphs - from the English poet Robert Browning, the English historian Henry Hallam and the German writer Friedrich Schlegel. Nitobe often refers to Confucianism, Buddhism, and interprets Shintoism, but the wildest thing is that Nitobe builds samurai morality on Christian principles. Of course, all this was done for a specific purpose.

“I wanted to show that the Japanese are really not so different from Westerners,” Nitobe said in an interview. Well, he showed it in such a way that you’ll rock it. (The existing translation into Russian by Elena Fedorova contains errors that distort the meaning of the text, so the translation is mine). “The seeds of the Kingdom of God, so desired and accepted by the Japanese mind, flourished in Bushido. Now his days are numbered... The only ethical system strong enough to fight utilitarianism and materialism is Christianity, in comparison with which Bushido, it must be admitted, is only “smoking flax” (quote from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, 42:3 - B.Z .), which, as the Messiah said, will not go out, but will only kindle into flames (he said this on another occasion - B.Z.) <...> The dominant, self-affirming “morality of the masters”, which Nietzsche wrote about, is itself similar in some respects on Bushido, is - if I am not much mistaken - a passing phase or temporary reaction to what Nietzsche calls the humble, self-denying morality of the Nazarene." Nietzsche? What the fuck did I just read?!

This is Nitobe’s argument. Moreover, he likens Japanese traditions to Christianity. In general, he himself professed it, and tried to interpret everything from this point of view. Thus, Nitobe associates seppuku - ritual suicide with the opening of the abdomen, also known as hara-kiri - with the Christian understanding of the abdomen as the center of vital energy. “They (the biblical Joseph, David, Isaiah and Jeremiah) supported the belief, common among the Japanese, that the stomach is the temple of the soul.” And he supports the samurai’s wearing of a sword with a quote from Romans 13:4: “But if you do evil, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain.”

Japanese Katana sword

The ability to fight with a sword was one of the requirements and values of the samurai and their bushido. You could follow the path of the sword if you devoted yourself entirely to caring for the katana and mastering martial arts with it. The katana is a razor-sharp sword that is always cared for and perfected by samurai. So they practice with the sword every day.

Museum in Tokyo. Katanas

The katana, also called the daito, along with the wakizashi, and the tanto (dagger) were part of the worn armor of the feudal samurai in Japan. Katana literally means "long sword" and wakizashi literally means "short sword". Both have a narrow and long blade that has only one sharp edge. It is different from the ordinary European knight's sword, which was sharpened on both sides. The katana was much lighter than European swords, which allowed samurai to strike very quickly.

Knights and Samurai: Comparison of Feudal Structures in Japan and Europe

Katanas are still highly respected throughout Japan and can only be purchased if you have proven yourself capable of fighting with Japanese swords (Kenjutsu). Prices for these swords can reach hundreds of thousands of euros.

Samurai and male love

Describing samurai moral principles, Nitobe makes a lot of references to European chivalry and speaks of unblemished honor and loyalty to service. Meanwhile, samurai education was, among other things, based on sex between teacher and student.

In modern Japanese society, sodomy is a severe taboo. But for most of its history, Japanese society was extremely tolerant of any type of sexual intercourse. Suffice it to say that for centuries in Japan there was a tradition of fucking - when men went to unmarried women at night for semi-anonymous sex.

Shintoism, the main Japanese religion, encouraged sexual intercourse. In the 7th century, Buddhism came to Japan, in which abstinence from sexual intercourse was considered a virtue - but sex between men was considered just a loss of control, while sex with a woman was much more sinful. In the 12th-16th centuries, there were more than 90 thousand Buddhist monasteries in Japan, in which the monks spent 10-12 years, and they had to adapt their sex life to these conditions.

Among Buddhist monks, there was a tradition that came from China, called in Japan nanshoku (“male way”) - adult monks (“nenja”) took in young men (“chigo ” ), with whom they lived sexually until a certain age, after which both - the teacher and the matured pupil - found new “students”. The relationship between teacher and student was subject to rituals and rules and was perceived as a necessary part of the education of a monk.

The samurai readily adopted this tradition. The 17th century Japanese author Ihara Saikaku wrote: “Edo was a city of bachelors, like the monasteries of Mount Koya.” Transparent. The samurai taught their wakashu (the so-called youths who reached the age of 10–20 years) the martial art and the correct way of life, and the youths were their squires, servants, and seconds. The relationship did not necessarily end when the youth became an adult. He could find his own wakashu and still maintain contact with the teacher. Of course, sex with women was not forbidden, but relationships between men were perceived as more important and noble. Such relationships were also very beneficial directly for military affairs: students defended their nenja selflessly, cultivating fearlessness in battle.

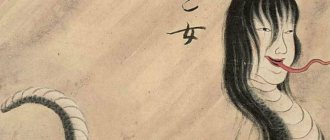

A gentleman with his wakashu, 1680s

In the Edo era (1603 - 1868), the conventional Japanese modern era, when the samurai became basically not a military, but an administrative class, nanshoku relations turned into a kind of attribute of the elite. More attention than before was paid not to military affairs, but to the art of love. There were even textbooks! Here are the chapter titles from a Japanese textbook on male relationships from 1657:

“On exchanging views” “How to answer the first letter” “How to politely go home in the morning” “On feeling disgusted after one meeting” “On wakashu diseases” “On kisses and paper napkins”

…and so on. Other classes wanted to adopt this “elite” way of life and relationships. In 1700, a million people lived in Edo (future Tokyo), and 400 thousand each in Kyoto and Osaka. Merchants and artisans who came from the outback considered nanshoku a sign of a wealthy and cultured person. 1650s - 1750s - a time of boom in prostitution, free love and other samurai joys.

1750s

Does Nitobe have anything about this? In the entire text, neither nanshoku, nor wakashu, nor other terms are mentioned even once, and in the chapter “Education and the Place of Women,” questions of love are literally obscured by lengthy discussions about duty and the essence of marriage. Why, the word “sex” is used only in the meaning of “sex,” and when talking about the family, Nitobe quotes the Bible and European philosophers. In general, his samurai are chastity itself.

But even purely historically, by the time Nitobe was born, male love had ceased to be an attribute of the elite and, in general, to stand out in any way. Well, Christian missionaries who came to Japan during the Meiji era, of course, informed the Japanese about the concept of “sin of Sodom.” Homosexuality began to be prohibited at the government level, but still flourished in the Satsuma region - a kind of samurai enclave.

In 1877, a year after the ban on wearing swords for untitled samurai, it was in Satsuma that the last major samurai uprising took place, defeated by the regular army and showing the backwardness of the samurai. The samurai way of life gradually died out, although the nanshoku relationship was still associated with true masculine valor.

By the beginning of the 20th century, samurai traditions had become purely marginal. New times have come for Japan - and in them Nitobe’s ravings received a new, terrible application.

Story

The Code of Bushido Warriors is a system of values, rules, etiquette, general ideas, and recommendations for behavior. It concerns interaction in society, being alone with your thoughts. The Code of the Japanese Samurai regulates the actions, thoughts, ideas, philosophical ideas, and morality of warriors. The set of rules is determined by historically established ideas about what is beautiful and right, and is based on the traditional values of the inhabitants of the eastern archipelago. As military principles, the code was formed in the 12-13th century. Its relevance is due to the fact that, along with the rules of combat, the code includes ethical values and instills in followers the idea of beauty and respect for art. The path of the warrior (this is how the word “bushido” is translated) reflects the essence of the samurai community as a social noble stratum.

Samurai are noble warriors

The Samurai Code emerged as a logical aspect of life under the shogunate, based on norms that existed in society long before this period. The sources of ideas reflected in the set of norms are Buddhism, Shintoism, the works of Mencius, Confucius. Key aspects are taken from Shinto, which harmoniously united ideas about the supernatural, love of nature and others, faith in the soul, and patriotism. Yamamoto Tsunetomo, who compiled the key book of the bushi path, took from Shinto the ideas of loyalty and love for one’s native country.

During the reign of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the “Code of Samurai Clan” was written, regulating in detail the behavior at home and in the service. The tenets of the bushi path are expanded by a description of the life of Takeda Shingen and the "Elementary Fundamentals of the Martial Arts." The Hagakure, the most important for the warrior's path, compiled by Yamamoto, appeared in 1716. The collection consisted of 11 books and became a kind of shrine for the military class.

Way of the Warrior

Heil shogun

“In various ways, Bushido seeped out from the class in which it originated and acted like a leavening agent among the people, setting the moral standard for the entire nation,” Nitobe wrote. It is ironic that, as we saw above, samurai debauchery was indeed popular among the people of the late Edo era. But of course, the author means something else - that the samurai principles of honor were adopted by ordinary people. This ideologeme was perfectly suited to support the patriotic spirit of the new Japanese army. Everyone wanted to feel like a noble samurai. And the goals of the new Japanese government were absolutely conquest-oriented.

Since the victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Japanese policy has become increasingly militarized. In 1910, Korea was annexed by Japan; After World War I, Japan also gained more territories and became one of the founding states of the League of Nations. And after Hirohito took the throne in 1926, the government finally set its sights on raising a nation of suicide warriors.

Kamikaze squad with swords - symbols of “samurai valor”

“Civilization and Enlightenment” and “Rich Country, Strong Army” became the official slogans. Ideologists began to actively seek out “suitable” texts from the past that would support the idea of dying for the state. As a result of these searches, the Hagakure book, created at the beginning of the 18th century and preaching the “Way of Death,” was discovered for two centuries as a forgotten book. Again, in the literature it is customary to call “Hagakure” a “statement of the principles of Bushido” - however, the word Bushido is not in the text of the book. A philosophical treatise on the meaninglessness of life, based on Confucian and Zen ideas, Hagakure began to be used for military propaganda in the 1930s. But not only her - in 1935, novelist Eiji Yoshikawa published the book “Musashi” about the adventures of the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi, which was soon turned into a super popular comic book. “Bushido” also gained extraordinary popularity in this context. Soul of Japan."

Book "Musashi"

Nitobe himself, it must be said, was horrified by what was happening - according to his convictions, he was a pacifist. During the short period that Nitobe sat in the Japanese Diet, he even prepared a speech denouncing Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi and his militaristic policies. But in vain - Japan’s aggressive aspirations were insatiable. In 1933, Nitobe died in Canada, where he was attending a political conference.

It is unclear what consequences Nitobe expected from his book, which so distorted the history of Japan - although it seems that the author himself did not even understand how wrong he was. It is not surprising that his book eventually found application in the militaristic ideology that the Japanese government zealously supported when it entered World War II on the side of the Reich. Of course, people who voluntarily go to death for an idea are beneficial to any commander. And as in the case of Nazi Germany, these ideas turned out to be false in their very essence.

Principles of Bushido

The name Bushido was not used until the 16th century, but the idea of a code developed from the Kamakura period (1192-1333). At that time, the Minamoto family founded Japan's first military government (bakufu), headed by a hereditary leader, the shogun. The content of the Bushido code gradually changed as the samurai class came under the influence of Zen Buddhism and Confucian thought, but its only constant ideal was the fighting spirit, including athletic and military skills, as well as fearlessness in battle. Frugal living, kindness, filial piety, honesty and personal honor were also highly valued. However, the highest duty of a samurai was duty to his master, even if it might cause suffering to his parents.

Bushido believes that man and the universe were created similar in both spirit and ethics. Along with these virtues, Bushido has the greatest respect for justice, benevolence, love, sincerity, honesty and self-control. Justice is one of the main factors of the samurai code. Vile deeds and unjust actions are considered base and inhumane. Love and benevolence were the highest virtues and princely deeds. Samurai adhered to a certain etiquette both in everyday life and in war. Sincerity and honesty were valued no less than their lives. Bushi no ippun (武士の一分), or "honor of the samurai", was a pact of complete loyalty and trust. Such contracts did not require a written pledge: this was considered beneath the dignity of a warrior. The samurai also needed self-control and stoicism in order to be fully respected.

MIYAMOTO MUSASHI, JAPAN'S GREATEST SWORDMAN

(“3”) Poetry.

Poetry was an integral part of the life of a samurai. It is difficult to find a biography or legend that does not use poetic lines. Possession of versification in the style of renga or haiku was considered no less a merit than the ability to wield a sword.

At the very beginning of the 10th century. The emperor ordered work to begin on compiling a new poetic anthology. This work was led by the famous poet Ki no Tsurayuki and brought to completion. “Kokin(waka)shu”, or “Kokinshu” (“Collection of old and new songs”), also consists of twenty scrolls, but includes only 1100 verses, thematically divided into seasonal cycles, songs of love, songs of separation, songs of wanderings, etc. etc. This anthology, despite the different level of its samples, became another contribution to the classical baggage of Japanese medieval literature. Among its authors, “six immortal poets” have already been identified. The most famous of them are Ariwara no Narihira and the poetess Ono no Komachi. “Kokinshu” became firmly established in the lives of educated Heians. Knowledge of her poems was indispensable for any courtier. A person’s personal merits or demerits were judged depending on how well he understood Kokinshu (Chinese poetry and Manyoshu too) and composed poetry himself.

The tanka became the most popular poetic form. Precise, capacious images, metaphors, the skill of elegant allusion, special key and seasonal words made it possible to express admiration for the natural world, love experiences, and philosophical reflections on the frailty of life in a laconic form... After “Kokinshu” several more anthologies were compiled; Thangka art experienced both ups and downs in its artistic level.

By the 15th century the custom developed of composing poems together, three of them, as if passing each other a poetic baton (renga) of tercets and couplets. A famous poet of the classical rank was Sogi (1421–1502). Renga, dividing the tanka into two parts, eventually gave life to a new, even shorter form - haiku, i.e. tercet (the terms “haikai” and “haiku” are equivalent).

The flourishing of haiku poetry is associated with the name of another great poet, Matsuo Basho (1644–1694). His poems are amazing: simple and sophisticated, sincere and wise, kind and sensitive.

Japanese poetry is inextricably linked with painting and the art of calligraphy.

Appearance of signs

When studying the symbolism of the samurai of Japan and the meaning that was attached to it, it is also necessary to turn to the hieroglyphs and the history of their appearance. Japanese characters, like most symbolic signs, appeared after they were borrowed from the Chinese. This is where Japanese writing and symbolism came from.

It is noteworthy that the same symbolic sign can mean completely different things. It all depends on how it is positioned among others. One of the most common symbols used by samurai is “fortitude.” Its components are hieroglyphs representing luck, friendship and several deities.

Samurai put this symbol on their clothes and weapons. It could be found on belts or long kimono collars. On weapons it was depicted on the guard or katana handle. It was believed that this symbol helps the samurai not to deviate from the Bushido code of honor, to be a good warrior and a devoted servant to his daimyo. For clarity, the article contains pictures with samurai symbols.