The Meiji Restoration is the name given to the global modernization that took place in Japan from 1867 to 1889. Officially, the Meiji era began with the accession to the throne of the new Emperor Mutsuhito, who made “Bright Reign” (which is how “Meiji” is translated from Japanese) the motto of his reign. But the prerequisites for the reformation arose earlier - during the shogunate of the Tokugawa clan.

Government

In February 1868, the Imperial Government declared to foreign countries that it was now legitimate. On April 6, 1868, the Emperor issued the Five Point Oath, setting out in it the basic principles of the political course.

Meiji Principles:

- collegial management;

- participation of estates in the development of solutions;

- rejection of xenophobia and compliance with international law;

- openness to the world to gain new knowledge.

Are you an expert in this subject area? We invite you to become the author of the Directory Working Conditions

On June 11, 1868, a new government structure was approved. In the US Constitution, the Japanese borrowed the formal division of government power into legislative, executive and judicial. Officials were required to be re-elected every 4 years.

Note 1

In September 1868, the city of Edo was renamed Tokyo, and in October the motto of the government was adopted - Meiji. On September 3, 1869, the Emperor moved the capital from Kyoto to Tokyo.

Despite the updates in the management system, the government was in no hurry to reform society. On April 7, 1868, it published five announcements in which it set out traditional provisions based on Confucian morality. The government called on citizens to obey their superiors, respect their elders, and be faithful in marriage; it banned public organizations, rallies, and the practice of Christianity.

Education

School education has also undergone dramatic changes. In 1871, a central institution was formed that was responsible for educational policy. The following year, 1872, this ministry adopted a resolution approving school education following the French example. In accordance with the established system, eight university districts were formed. Each of them could have 32 schools and 1 university. At the middle level, separate districts were created. Each of them was supposed to have 210 primary educational institutions.

The implementation of this resolution in practice was associated with a number of problems. Mainly, the ministry did not take into account the real capabilities of citizens and teachers. In this regard, a decree was issued in 1879, according to which the district system was abolished. At the same time, initial education was limited to school according to the German model. For the first time, educational institutions began to appear in which boys and girls studied together.

Administrative reform

To form a unitary Japan, the elimination of the federalist structure was necessary. During the civil war, the government confiscated the shogunate's properties, which were divided into prefectures. But the territories of the principalities remained outside control. On January 20, 1869, four pro-government daimyos submitted a petition declaring that everything belonged to the Emperor. In February 1869, officials proposed to the Emperor to subordinate their territories to the government. The daimyos from Satsuma, Tosa, Choshu and Hizen agreed to the proposal, returning the lands to the monarch along with the population. In July 1868, the government ordered the other daimyo to do the same, which was carried out without resistance. Only twelve princes did not voluntarily hand over the land registers, but later they obeyed the order.

Finished works on a similar topic

Coursework Meiji Restoration 480 ₽ Essay Meiji Restoration 280 ₽ Test paper Meiji Restoration 190 ₽

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

In exchange for lands, princes became heads of central government offices in the regions and received a salary. Although the lands were transferred to the state, the khans themselves were not abolished. Daimyo retained the right to collect taxes and form troops on entrusted lands, thus remaining semi-autonomous. This half-hearted policy caused discontent in the regions. On August 29, 1871, the government proclaimed the establishment of prefectures instead of khans. The daimyo were moved to Tokyo, and dependent governors were appointed in their places. By 1888, the number of prefectures was reduced from 306 to 47, Hokkaido was allocated a special district, and the cities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka were equated to prefectures.

Japanese opposition during the Meiji era

From the mid-1870s, an opposition began to form in the country, dissatisfied with some of the transformations. Various statements about Japan's future path appeared on the pages of newspapers, the number of which also increased sharply. Although most of the population still remained passive, thanks to the press, ordinary Japanese began to get acquainted with the political situation and form their own opinion about the processes taking place in the country.

Japanese opposition at the time consisted of two camps: those who believed that democratic reforms were insufficient, and those who believed that reforms had already gone too far. In 1874, the first Japanese political party, the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, arose, expressing the views of the first camp. Basically, it included small landowners and bourgeois who did not receive such huge subsidies from the government as the large capitalists. Their main demand was the creation of a parliament. But very soon a radical wing arose within the party, demanding civil rights and freedoms common to the entire population, and defending, first of all, the interests of the peasantry.

The core of the conservative opposition was the samurai, most of whom were unable to fit into the new capitalist society. In addition to losing their status, they were worried about the government's refusal to conquer Korea. The opposition believed that this was humiliating for Japan. The leader of the dissatisfied was the “last samurai” - the famous Takamori Saigo. He also believed that Japan should pursue an aggressive foreign policy, however, his political and philosophical views were not limited to this. Saigoµ found inspiration in the teachings of bushido and the romantic ideals of the bygone era of samurai. Retiring to his home prefecture of Kagoshima, Saigo opened a school for “real samurai” where he trained cadets in accordance with his own philosophy.

In 1877, Mutsuhito finally abolished samurai privileges. The number of Takamori Saigo's students at that time reached 10 thousand. It was a full-fledged military unit that responded to the government's actions by seizing the arsenal and launching a campaign against Tokyo. The confrontation between government troops and Saigo's people continued for several months; in one of the battles, the rebel leader was wounded, after which he committed suicide. The uprising was soon suppressed. Even though Saigoµ was the leader of the rebellion, the population treated him with respect. Even Emperor Mutsuhito himself did not want to deprive his commander of all ranks and outlaw him until the very end.

Government reform

The structure of the Japanese government of the 8th century was taken as the basis for the new vertical of executive power. On August 15, 1869, the government was divided into three chambers.

The Main Chamber had the functions of a cabinet of ministers. It included a great minister of state, ministers of the right and left, and advisers. The left chamber was the legislative body. The right chamber included eight ministries. Most of the positions in the government were occupied by people from the principalities of Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa and Hizen.

Cultural transformations

The government was aimed at modernizing the state in all spheres of life. The authorities actively promoted the introduction of innovative Western ideas and models. The majority of representatives of the intellectual part of the population reacted positively to these changes. Thanks to the efforts of journalists, new ideas were widely disseminated among the public. A fashion for everything Western, progressive and fashionable has appeared in the country. Fundamental changes have occurred in the traditional way of life of the population. The most progressive centers were Kobe, Tokyo, Osaka, Yokohama and other large cities. Modernization of culture through borrowing the achievements of Europe began to be called according to the slogan “Civilization and Enlightenment”, which was popular at that time.

Military reform

The most important task of the imperial government was the organization of a new combat-ready army. The troops of the principalities, consisting of samurai, were reassigned to the Ministry of War. On January 10, 1873, the government introduced universal conscription. All men over the age of 20 were required to perform military service, regardless of social origin. Only heads of families and their heirs, students, officials, students and persons who paid a ransom of 270 yen were released.

At the same time, police units were created. Until 1872 they were subordinate to the Ministry of Justice, and then to the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The last resistance of the bakufu forces

In May 1869, the forces of the old bakufu government in Ezo, led by Enomoto Takeaki, whose main stronghold was Fort Goryokaku in Hakodate, surrendered to the new government (end of the Boshin War). Thus, the new government united the entire territory of Japan under its leadership. In the same year, the new government ordered the feudal daimyo to return the lands and peasants belonging to the principalities to the emperor. However, this was of a formal nature: the owners of the principalities began to be called “tihanji” in a new way, while continuing to rule in their territories.

Meanwhile, the Boshin War was fought by vassals of various lords, and at the end they mostly went home, and the government had virtually no military forces of its own. Therefore, anticipating the second Satcho War, the principalities began to actively carry out military reforms. In the principality of Kishu and some others, conscription was introduced and a 20,000-strong modern army was formed according to the Prussian model.

"The Great War in Hakodate" (Hakodate City Museum)

Social reforms

The imperial government pursued an active social policy. On June 25, 1869, two privileged classes were formed - titled and untitled nobility. The first included the capital's aristocrats and former daimyos, the second included the middle and small samurai. In this way, the government tried to overcome the confrontation between samurai and aristocrats and eliminate the medieval “master-servant” model.

The imperial government also announced the equality of peasants, artisans and merchants, regardless of occupation and position. In 1871, the government classified them as pariahs who had been discriminated against during the Edo period. The common people were allowed to have surnames, which previously were exclusively among samurai, and the nobility were allowed inter-class marriages. Restrictions on travel and changing professions have been lifted.

The nobility was completely supported by the state. It received an annual pension amounting to 30% of the country's budget. To ease this financial burden, in 1873 the government published the “Law for the Return of Pensions to the Emperor,” obliging the nobles to refuse to receive pensions in exchange for one-time bonuses. But the problem was not solved, and the debt for pension payments was growing, so the authorities in 1876 finally canceled their accrual and payments. The legal difference between samurai and common people disappeared. To ensure their existence, part of the privileged class became employees: clerks, police officers or teachers. Many took up farming. Those who went into commerce quickly went bankrupt due to lack of skills. To save samurai, the government provided subsidies and encouraged the development of semi-wild Hokkaido.

Note 2

But these measures were not enough, which in the future became the cause of unrest.

Economic situation of Japan in the 19th century

In parallel with the class and legal reforms, the government carried out an agrarian reform. Prohibitions on the sale and purchase of land that had existed since 1643 were lifted; Land surveying was carried out, during which owners began to be issued special certificates (tiken) of land rights. Thanks to this, a significant number of landowners who previously used the land as vassals acquired real ownership rights; This also affected small independent peasant tenants. In 1876, cash pensions for samurai were introduced instead of rent, which deprived them of a significant part of their income. A single land tax was established, amounting to 3% of the value of the land.

Industrial production in Japan was characterized by uneven development of industries: textile production developed rapidly, while metallurgy developed slowly (only at the beginning of the 20th century did the development of metallurgy accelerate). In general, Japanese industry was characterized by an increase in the number of small enterprises.

The weakness of the Japanese bourgeoisie determined the significant participation of the state in the development of industry. At the expense of the state, transport and communications were created, heavy industrial enterprises were built, which were soon leased or sold to private individuals. Thus, the large concerns Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Yasuda, and Asano were created, which established complete control over the industry.

At the same time, small enterprises predominated quantitatively. In terms of technical equipment, Japanese industry was inferior to European and American ones. But despite this, Japan became one of the great powers, a rival of European countries in the Pacific region.

The concentration of capital and the formation of financial capital were also a characteristic feature of the economic development of Japan at the beginning of the 20th century. Already in 1897, the country's five largest banks owned 25% of all deposits. Like other countries, Japan is also beginning to export capital, investing it in other, less developed countries, exploiting their natural resources and cheap labor and making large profits. Thus, in 1895 a sugar factory in Taiwan, in 1896 a weaving factory was built in Shanghai, and railways and communication networks were built in Korea and China.

Development of industry and construction

The country's transition to the industrial vector of development led to industrial growth and the emergence of new technologies in the country. In 1872, under the direction of European engineers, the first railway was opened, connecting Tokyo with Yokohama. The locomotives were brought from Europe, and the station building was designed in the USA. The first passenger was the emperor himself. At the same time, for movement on the streets, based on the English model, left-hand traffic was adopted.

In 1877 and 1881 Industrial exhibitions were held in the country to introduce promising global technologies in industry and agriculture. In 1877, Alexander Bell established a telephone line between Tokyo and Yokohama.

Instead of traditional wooden buildings, exposed to a strong fire danger, extensive stone construction began in cities, and pavements were also covered with stone.

Meaning

As a result of the restoration, Japan “jumped” into modern times. The army was reorganized. The construction of a full-fledged military fleet has begun. Government reform, social and economic reforms, as well as the rejection of self-isolation have created favorable conditions for the development of Japan into a competitive, including economic, society.

On the one hand, Japan avoided the risk of becoming completely politically dependent on European powers or the United States. (The closest European power to Japan was and is Russia. True, Russia did not pursue a policy similar to English colonialism, preferring to extract benefits in other ways.) On the other hand, having joined the economic and political race with Europe, Japan has gone far ahead in comparison with other eastern countries. -Asian states.

Source: Wikipedia

International relationships

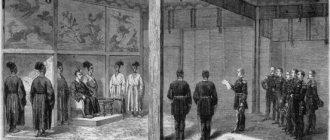

The first official visit in Japanese history by a representative of the ruling family of a foreign power took place in 1869. It was a visit to the Emperor by the Duke of Edinburgh. To receive a high-ranking foreigner, diplomatic court rules were hastily developed, since representatives of foreign powers had never before been received at such a high level and the Emperor of Japan was not considered equal to other monarchs. After the exchange of gifts, Emperor Mutsuhito gave the Duke a poem he had personally written for Britain's Queen Victoria:

If you rule with a thought about people, Heaven and Earth will remain together forever. — translation by A.N. Meshcheryakov

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Japan declared neutrality, taking part in the political life of the European great powers for the first time. In 1871, an equal treaty was concluded with China. An unsuccessful attempt was also made to revise the unequal treaties for Japan with Western countries and Russia, for which Foreign Minister Tomomi Iwakura went on a diplomatic trip to the United States and Europe in November 1872. However, to represent Japan in the West, a portrait of the emperor was required, and tradition forbade depicting rulers; this ban had to be lifted by photographing the monarch in palace attire. When visiting St. Petersburg, Tomoti Iwakura acquired portraits of Peter I, whom he treated as his idol.

Religion

After the policy of restoring ancient statehood was proclaimed in 1868, the government decided to make the local pagan religion Shinto the state religion. In this year, a decree was approved distinguishing between Buddhism and Shinto. Pagan sanctuaries were separated from monasteries. At the same time, many Buddhist temples were liquidated. An anti-Buddhist movement formed in the circles of officials, townspeople and intellectuals. In 1870, a declaration was proclaimed, according to which Shinto became the official state religion. All pagan sanctuaries were united into a single organization. The emperor became its head as a Shinto high priest. The birthday of the monarch and the date of the founding of the new state were declared as public holidays.

Life

General modernization has greatly changed the traditional way of life of the population. Short hairstyles and Western clothing began to be worn in cities. Initially, this fashion spread among the military and officials. However, over time, it entered the general public. Prices in Japan for various goods were gradually equalized. In Yokohama and Tokyo, the first brick houses began to be built and gas lamps were built. A new transport has appeared - the rickshaw. The development of industries began. Western technologies began to be introduced into production. This made it possible to make prices in Japan accessible not only to the privileged classes, but also to ordinary people. Transport and publishing were actively improved. With their development, the fashion for Western goods entered the province.

However, despite significant positive changes, the modernization carried out caused serious damage to the traditional spiritual values of the population. Many cultural monuments were taken out of the state as trash. They settled in museums and private collections in Great Britain, France, and the USA.